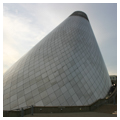

With its strikingly tilted, stainless steel–clad cone housing a glassblowing studio, also known as a hot shop, the Museum of Glass has become a significant feature of Tacoma’s revived waterfront. Since its opening in 2002 on the west side of the Thea Foss Waterway that leads into Commencement Bay, the building has contributed to the city’s efforts to create a cultural zone, along with the University of Washington Tacoma, the Washington State History Museum, and the Tacoma Art Museum.

The Foss Waterway area first developed as a warehouse district in the nineteenth century because of its proximity to the bay and the railroad. Warehouses and mills rose up along the waterfront, but as Tacoma’s economy gradually deteriorated during the twentieth century, the waterway also declined. Industry left the waterfront heavily polluted. In 1983, the Environmental Protection Agency listed the waterway as part of a larger “Superfund” site that included Commencement Bay. This step helped launch the waterfront’s gradual cleanup and subsequent economic redevelopment into a mixed-use area with residential buildings, commercial space, and a public esplanade running along the water.

Tacoma’s waterfront had long been isolated from the rest of downtown by the railroad and later also by I-705, completed in 1990, which bypassed downtown. Only a few roads running underneath the highway and over the tracks provided vehicular access; pedestrian access was even more difficult. Nevertheless, during the planning stages for the museum, the site seemed advantageous because it was just down the hill from the University of Washington Tacoma campus and the Washington State History Museum.

The idea for a museum dedicated to glass art developed in the early 1990s, initially inspired by the work of artist Dale Chihuly. A Tacoma native, Chihuly has done more than any other American artist to raise the profile of glass art to the status of fine art. Philanthropists George and Jane Russell launched the effort to raise funds for the museum and a bridge of glass that would connect the building to the rest of Tacoma. The project had some hiccups, however; in 1998, fundraising slowed, the founding museum director quit, and Chihuly distanced himself from the museum project, but continued work on the bridge of glass. Despite some delays, the mission of the institution expanded to focus on glass art more broadly.

In 1996 the museum board hired world-renowned Canadian architect Arthur Erickson of Vancouver, British Columbia, to design a signature structure that would serve as a destination for visitors. Erickson’s firm collaborated with Vancouver architect Nick Milkovich and the Tacoma-based firm Thomas Cook Reed Reinvald Architects (now TCF Architecture). By hiring Erickson, the Museum of Glass followed the trend of other museums that have commissioned “starchitects” to create unique buildings whose architecture is as much of an attraction as the exhibits displayed within—if not more so. Two other museums in the district share similar objectives: the Washington State History Museum designed by Charles Moore and Arthur Andersson, completed in 1996, and Antoine Predock’s 2003 Tacoma Art Museum with its 2014 addition by Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig Architects.

Although Erickson was commissioned to design the museum, he did not work on the Bridge of Glass, which was a collaboration between Chihuly and architect Arthur Andersson. The construction of the pedestrian bridge, over the railroad tracks and I-705, has been instrumental in physically connecting the museum with the rest of Tacoma. From Pacific Avenue one walks through the open arch of the Washington State History Museum and across the bridge, which serves in part as a showpiece for some of Chihuly’s artwork. Although the bridge provides important pedestrian access to the museum, its design does not flow as smoothly with the museum as it might have. The designs of both the museum and the bridge had to be scaled back because of budget constraints. This change perhaps explains the bulky glass display cases overhead and along the side of the bridge that obscure views of the museum and the waterfront.

Nevertheless, the bridge offers an important point of access to the museum. Architecture critic Trevor Boddy has noted Erickson’s use of the promenade architecturale, favored by Le Corbusier, a concept Erickson also employed in Vancouver, British Columbia, at Robson Square and the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. In Tacoma, the promenade begins up the hill on the University of Washington Tacoma campus where one can see the museum’s cone through the open brick arch of the Washington State History Museum. Crossing Pacific Avenue, walking through the arch, and turning left takes the visitor to the west end of the Bridge of Glass. Walking over the bridge leads the visitor onto the roof of the museum. From there one must continue through a series of spaces on the east side of the building to arrive at the entrance. One can either turn right and walk down a curved set of wide concrete stairs that wraps around the cone or turn left and descend along a concrete ramp that zigzags around a series of reflecting pools with infinity edges, another feature of Erickson’s designs, and plazas. Either route descends two levels to the museum’s entrance on the east side of the building facing the water. An elevator located near the east end of the Bridge of Glass provides a third point of access to the main entrance.

Despite the museum’s modern design, it possesses numerous features that help situate it in a postindustrial city of the Pacific Northwest. Although the museum is a private, non-profit organization, Erickson intended its plazas to act as public space. The roof, plazas, and entrance all provide views of the bay, the Port of Tacoma, Mount Rainier, and the hot shop’s stainless steel cone with its diamond-shaped panels. The cone intentionally echoes the dome of Mount Rainier, but also the sawdust burners used in timber processing, once a common feature of the Pacific Northwest landscape. The four levels of the building, including the roof, offer strong horizontal forms that contrast with the curved form of the hot shop. Though connected to the city by the Bridge of Glass, the museum is oriented toward the water, with its ramps, pools, and entrance plaza all facing the Foss Waterway and Commencement Bay rather than the city.

Ironically, for a museum of glass, the building itself employs relatively little glass in its construction. Budget constraints required Erickson to cut back on the material’s use; even his desire to use poured-in-place concrete gave way to less expensive prefabricated concrete panels. The upper level of the museum’s east facade looking toward the water and the west side that faces the tracks, the freeway, and the city have grids of mostly opaque glass set above a concrete foundation. Curved, tubular exhaust vents mimic the smokestacks of a ship or factory. The prow-shaped structure on top of the roof that houses the elevator also evokes a ship. Below, clear glass opens up the wall looking over the entrance plaza to admit natural light into the lobby.

The interior of the museum consists primarily of large, open areas to accommodate a cafe, shop, education center, and exhibit space. The cone cuts through the walls of the museum; its stainless-steel base can be seen from the lobby and the glass-walled cafe. The hot shop within the cone is the museum’s most popular feature and provides seating for over 100 visitors to watch the glassblowing process. Its interior is nearly as striking as its exterior, with tall vertical sections of steel terminating in a glazed oculus at the top. In contrast, the main exhibition hall is a large, functional rectangular space with concrete floors and bare walls. Its 13,000 square feet provide a blank slate for displaying a variety of artworks. The large, open lobby offers additional room for exhibits and guest circulation space.

One of the more architecturally dazzling buildings constructed during Tacoma’s cultural renaissance at millennium’s turn, the Museum of Glass has helped transform the city’s waterfront and draw tourists to the city. Flanked to the south by Albers Mill, an old brick flour mill now repurposed as artists’ lofts and a glass art gallery, and to the north by high-end apartments and condominiums, the museum has become the destination it was designed to be. The stainless-steel cone of the hot shop, rising above the tan, horizontal forms of the museum, serves as an important architectural landmark, as recognizable among Tacoma’s landmarks as Union Depot and the Tacoma Dome.

References

Boddy, Trevor. “Landscape of Ideas: Museum of Glass, Tacoma, Washington.” Canadian Architect47, no. 11 (November 2002): 30-36.

Cheek, Lawrence W. “Tacoma's Cone [Museum of Glass].” 91, no. 8 (August 2002): 80-87.

“Museum of Glass.” Tacoma-Pierce County Buildings Index. Tacoma Public Library, Tacoma, WA. Accessed August 29, 2015. https://www.tacomalibrary.org/.

Pastier, John. “The Smell of Success: Tacoma, Washington, Tries to Escape its Past Mistakes—and the Shadow of Seattle—by Invigorating its Downtown's Cultural Life.” Metropolis22, no. 8 (April 2003): 90-93+.

Raether, Keith. “Glass Museum Director Quits; Search Begins.” The News Tribune(Tacoma, WA), April 15, 1998.