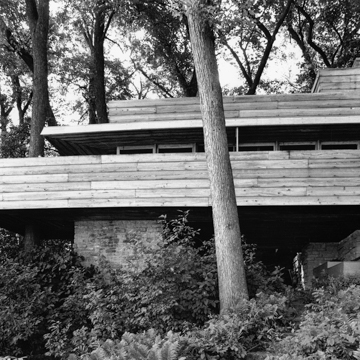

Perched among trees on a hillside above Lake Mendota, the Pew House is one of Wright’s finest Usonian designs. Wright’s Great Depression–era answer to the need for low-cost housing, the Usonian house achieved economy by using prefabricated components, inexpensive wooden walls, efficient plans, and underfloor heating. The house of research chemist John Pew and his wife, Ruth, embodies Wright’s ideals, with its cypress and limestone surfaces blending naturally into the surrounding environment. The house’s massing responds to the sloping terrain. The hillside anchors the house at one end, but then it drops sharply away, leaving the building suspended above a ravine. Except for a supporting limestone pier, it seems to float in air.

The house is organized in three parts, stepping down toward the lake. From Lake Mendota Drive, the topmost layer reveals only a square box containing bedrooms, with rectangular window canopies and a yawning carport wrapping around its corners. To the rear, the house expands into a wide, open balcony, and below that, the largest and lowest story contains the rest of the living space. Wright often opened the rear of a house to the landscape, and here the Pews’ living room leads to a cantilevered balcony overlooking the water. The diagonal placement of the rectangular house exposes two sides to the expansive lake view. Throughout the design, ribbon windows, projecting terraces, and lapped bands of cypress siding lend a typically Wrightian sense of horizontality.

Wesley Peters, Wright’s son-in-law, once told Wright that the Pew House should be known as “a poor man’s Fallingwater,” after the famous Edgar J. Kaufmann House, with its cantilevered and stepped massing, which Wright designed in Bear Run, Pennsylvania. In response, Wright said no; Fallingwater was a “rich man’s Pew House” (Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings, 1990). He drew on the Pew design to create similar Usonian houses in Arizona, Illinois, and Michigan.