This block-long district-within-a-district traces eight decades of change in commercial building design. The story begins just after the Civil War, in the 1860s and 1870s. Toward the south, three- and four-story structures illustrate the era of small-scale Italianate commercial architecture better than any other assemblage in the city. Small’s Building at 704–708 N. Milwaukee Street and Bowman’s Block Number 1 at number 715–717 date from 1866 and are textbook examples of the Italianate style. Rare hand-carved wooden brackets adorn Bowman’s cornice. Other buildings with Italianate traits include the two Brown’s Buildings at numbers 710 and 712–714, built in 1866 and 1874, respectively. Buildings like these were the architectural mainstay of Milwaukee’s central business district during and after the Civil War.

By the late 1870s, Milwaukee entered a period of rapid economic growth, especially in heavy industry. The rise of manufacturing fueled the expansion of retail, financial, and professional enterprises. On Milwaukee Street, this heady era saw the construction of ever-larger commercial buildings and the waning of the Italianate style in favor of the more exuberant High Victorian Gothic and Queen Anne. Edward Townsend Mix designed the High Victorian Gothic Arcade Block at 718–722 N. Milwaukee Street and the Stevens Block next door at number 724–728, both built in 1877. Foliated and geometric patterns in stonework clad the buildings. Stone decorations were costly but were more prestigious than brick or sheet metal embellishments.

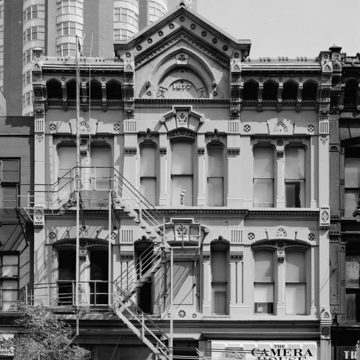

Across the street at number 725–729 the Conroy Building (1881) celebrates the commercial form of Queen Anne. The ebullient facade, flashing its expensive imported red brick, red sandstone, and terra-cotta cladding, stands out from its mellow cream brick neighbors. The bold composition combines broad second-story oriels, wide-arched third-story windows, and unusual false gables on the top floor.

By 1900, businesses needed more clerical workers as they devised more elaborate management hierarchies, and the resulting demand for more office space reshaped urban skylines. Real estate mogul Daniel Wells Jr. hired Henry C. Koch to design a fifteen-story office tower for the corner lot at 324 E. Wisconsin Avenue. Koch’s Beaux-Arts Wells Building opened in 1901 as Milwaukee’s largest office block. The first two stories retain most of their original copper and cast-bronze sheathing and the upper thirteen stories their pressed-brick and terra-cotta cladding, but the enormous terra-cotta cornice was removed after 1945. The Wells Building’s grand arched entranceway has inset tile, the vestibule a domed mosaic ceiling, and the lobby white marble paneling.

At the north end of the block at 732 N. Milwaukee Street, the John Mariner Building illustrates 1930s commercial architecture. Created by Eschweiler and Eschweiler in 1937, the six-story structure is clad with smooth Bedford limestone blocks incised with vertical ribs and low-relief carvings. These features, along with the rounded corner and characteristic banded windows, are evocative of this decade.