You are here

Charnley-Persky House Museum

Designed in 1891 and built the following year, the James Charnley House is an intriguing collaboration between Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, during a master/student moment in their professional relationship. Created when large commercial projects like St. Louis’s Wainwright Building and the Transportation Building at the Columbian Exposition occupied much of Sullivan’s time, he designed the Charnley House in its broad strokes—the massing, exterior, and the public areas on the first floor—leaving Wright to author the house’s details and give shape to the upper floors of the building. Both designers sought a natural architectural expression: Sullivan’s portions employed flat planes relieved by his abundantly detailed organic ornament, while Wright’s work directly referenced Japanese architecture, understood at the time as a “purely aesthetic,” more wholly natural expression. The combination is not entirely harmonious, and in that tension, we see an architectural conversation between the lieber meister and his most successful apprentice, each pursuing different paths to escape the revivalism dominating contemporary architecture.

Built on a corner lot on Chicago’s north side, on the western end of the first long block west of the lake, the Charnley House powerfully contrasts the taut planarity of its massing with an intricacy of detail focused around the front entry. Roman brick walls, untrimmed window openings, and the simply cut stone watertable and stringcourse express clarity, while the second-floor porch overhanging the main entrance, with its colonnade and profusion of densely carved ornament, gains richness in its contrast with the simplicity of the rest of the structure. Copper cornices with decorative geometric bands overhang at the porch and the flat roofline.

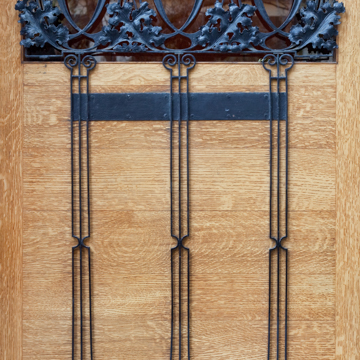

A stained oak door marked with intricate ironwork leads into the Charnley House, and a fireplace with richly curving abstract decorative mosaic tile welcomes the visitor into the central hall. A wide stair with a profusely carved newel leads upstairs, drawing the eye upward to Sullivan’s carved wood guardrails at the second floor, which are topped by a Japanese-influenced spindle screen, evidence of Wright’s hand. Graceful, untrimmed, round-arched doorways draw the visitor into the ground-floor living room and dining room, and the first-floor walls are finished with rough plasterwork above high wood paneling. Deep, wood-paneled crown moldings wrap each room, and built-in bookshelves and sideboards minimize the need for freestanding furniture. Wright exercised greater control at the second and third floors, which each accommodating two bedroom suites with private bathrooms and closets. High wood baseboards, blank plaster walls, and narrow picture rails, along with the frosted interior windows that evoke shoji screens, all directly reference Japanese architecture. The woodwork throughout the main part of the house is stained white oak, uniting the house and bringing an organic richness appropriate to both Sullivan’s and Wright’s visions. A tight rear stair at the southeast corner of the site connects the basement to the third floor, and kitchen and service spaces occupy the basement level.

Sullivan designed the house for his close friend James Charnley, a wealthy lumberman. In 1890 Sullivan had designed adjacent vacation homes for himself and the Charnley family in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. In 1882, the Charnleys commissioned Burnham and Root to design a large house at Division Street and Lake Shore Drive. A decade later, the deep porches and expansive footprint of their residence proved difficult to maintain. With their youngest child leaving home, and the neighborhood becoming increasingly built-up, the Charnleys decided to commission Sullivan to design a smaller, lower-maintenance structure. The innovative stylistic aspects of the house, especially the Japanese influences, established the Charnleys as informed consumers of contemporary aesthetics, even as its small footprint released them from the most onerous duties of entertaining. The Charnleys remained in the house for a decade until they retired to South Carolina in 1902. A series of families subsequently owned the house, and in 1927 the owners built an addition on the south side of the building.

In 1986 the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) purchased the house and undertook a major restoration. They removed the 1927 addition, undertook paint and plaster studies, and returned portions of the house to its original state. SOM intended to run a non-profit design center in the house, but found the costs of the building daunting. In 1994 they rented the house to Seymour H. Persky, a philanthropist interested in securing the house’s future. Persky offered to purchase the building and donate the property to the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) for use as its headquarters. In 1995 SAH, the country’s oldest and largest scholarly organization for the study of the history of the built environment, relocated its offices from Philadelphia to Chicago, and has since served as the steward of the Charnley-Persky House, carefully maintaining the structure and opening it to the public for guided tours.

References

Boles, Daralice D. “From House to Headquarters.” Progressive Architecture 70 (April 1989): 76-81.

Cannon, Patrick F. Louis Sullivan: Creating a New American Architecture. Portland OR: Pomegranate, 2011.

Longstreth, Richard ed. The Charnley House: Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of Chicago’s Gold Coast. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Morgan, Keith. “The Charnley-Persky House: Architectural History and Society.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 54:3 (September 1995): 276-77.

Roberts, Ellen E. “Japanism and the American Aesthetic Interior, 1867-1892: Case Studies by James McNeill Whistler, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Stanford White, and Frank Lloyd Wright.” Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 2010.

Society of Architectural Historians, “James Charnley House,” Cook County, Illinois. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 1997. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.