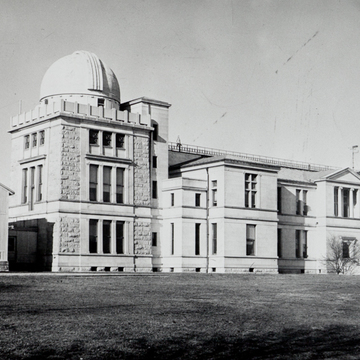

In 1881 the navy selected the present 73-acre site for a new naval observatory, a large, high tract of ground outside the developed parts of the city. A circle 1,000 feet in diameter was laid out so that vibrations from future road traffic would not disturb delicate timekeeping and astronomical instruments. When Massachusetts Avenue was extended during the 1890s, it curved around the circle's northern perimeter. All of the large group of buildings designed by Richard Morris Hunt for the observatory survive. Some were purely utilitarian in nature, including a boiler house, dynamo building, and stables. The scientific buildings include a circular observatory for a 26-inch telescope and a multi-functional, four-part structure (the James Melville Gilliss Building) that appears to have been built in stages but was in fact designed as a unit and completed in 1892. Its central portion, a long two-story rectangle intersected by three projecting wings, contains administrative offices. A circular library with a low conical roof is attached at the east end; on the west a three-story tower rising above the main block is topped by a revolving dome housing a 12-inch Clark refractor telescope. To the west of the tower is a single-story gabled utilitarian looking building that was designed to house a transit telescope (which observes only stars that pass overhead along the meridian).

The simple geometries, severe architectural treatment, and disjointed nature of the Gilliss Building's design led Washington architect and critic Glenn Brown, writing in the American Architect and Building News in

The metal transit telescope shed is most distinct, visually linked to the rest of the complex only by rusticated stone foundations. The tower walls are battered, with solid corners erected of rock-faced marble, but belt courses, central tripartite window frames, entablature, and balustrade are smooth, sawn marble. Classical details alternate between very reduced to totally abstract. Doric pilasters used to divide and frame the windows are plain but recognizable. The entablature above the second-story windows distinguishes this level as most important; its frieze is composed of three narrow bands (used with Ionic and Corinthian orders) upon which Hunt superimposed a plain raised circular disk above each pilaster, a Doric feature. The cornice and balustrade are more boldly abstract, solid marble slabs with triangular, arched, and oblong shapes set side by side with pronounced seams to stress a different aspect of tectonic structure from the rough and smooth walls below.

The central administration building has the least surface decoration but is the most sculpturally composed, with interpenetrating volumes clearly demarcated. With the exception of the Ionic in antis porch above the south entrance, Doric pilasters are used to divide double windows. Those on the first floor carry their entablature moldings around three sides while those on the second story have moldings only on their front face. Their resulting abstract, linear profiles are yet another comment on the nature of architectural structure. Two distinctive abstract features of the tower and office block are combined on the library's walls. The Ionic-Doric frieze encircles the top of the rotunda, while wide superimposed profile pilasters cut through five horizontal bands. Despite their broken massing and textural variations, all three of the building's marble sections are horizontally bounded by two wide plain belt courses and a common cornice line. Hunt employed many strategies of avant-garde French rationalist thinking in his design for the Naval Observatory, the architectural expressions of which are rare in America.