Although the Civil War had been over for 34 years, the developers of Union Block in Boise communicated their political allegiance when they named the building. Their Union sympathies may also have influenced their decision to engage John Tourtellotte, a self-taught architect with Connecticut Yankee roots, who migrated west to Boise after completing his architectural apprenticeship in Massachusetts.

The building’s five-man founding partnership of Boise’s mayor, Fort Boise’s commandant, and three key businessmen conceived the Union Block as a sub-dividable, mixed-use building. Each of its five arched, two-story bays framed five individual storefronts at street level and second-floor windows illuminating a ballroom, professional offices, and living quarters for the building’s owners. Each of the five partners owned a complete two-story bay including the corresponding section of the basement below.

In its massing, detailing, and materiality, Tourtellotte’s design for Union Block exhibits Richardsonian Romanesque influences. Indeed, he may have known Richardson’s work directly from his youth in New England, where he could have encountered such prime examples as the R. and F. Cheney building in Hartford, Connecticut. Travel and brief work experiences in St Louis, Chicago, and Denver exposed Tourtellotte to additional contemporary architectural currents and after he settled in Boise, he would have become familiar with local examples of Richardsonian Romanesque.

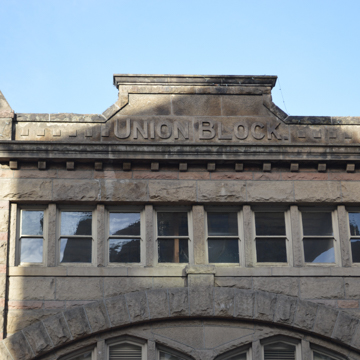

Completed in 1902, the Union Block’s main facade features flattened stone arches, a stepped parapet, and a denticulated cornice, rendered in locally quarried Table Rock sandstone. The building’s 120-foot-long Idaho Street facade is faced with gray sandstone and highlighted with red sandstone. Here, as in several of his Boise buildings, including the Idaho State Capitol, St John’s Cathedral, and Boise City National Bank, Tourtellotte displays his proficiency at using stone as an expressive architectural material. Of course, since high quality stone was readily available locally, it was an obvious choice for construction during Boise’s early years of development. Boise Table Rock sandstone eventually earned a national reputation, and it is found in buildings on both coasts, including downtown Portland, Oregon, and at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

The building’s location at the center of a block in the heart of downtown Boise limited natural lighting in the Union Block’s interior spaces, but Tourtellotte had anticipated the block being developed with party wall buildings and used strategies to introduce daylight deep into the Union Block’s core. Second-story circulation is organized as a network of interior streets, awash in daylight from eight gabled skylights. He located transoms and interior window walls along hallways to allow light from the skylights to penetrate interior offices and apartments. Passive cooling, providing relief from summer heat in the high desert, was achieved through use of operable hallway transoms, night flush cooling, and thermal mass inherent in the building’s thick masonry walls. The second-story meeting hall/ballroom used expansive fenestration at each end of the large room to bring in as much light as possible. The building’s organization and its light and ventilation made it appealing to a broad spectrum of tenants over the years.

The Union Block fell into decline after World War II, as Boise’s historic downtown was abandoned in favor of new buildings on the suburbanizing frontier. In 1965, the Boise City Council formed the Boise Redevelopment Agency (B.R.A.) to pursue federal funding for redevelopment of so-called blighted areas, including downtown. Consistent with urban renewal throughout the United States, the B.R.A. adopted a tabla rasa approach: twelve commercial blocks were condemned with the intention of demolishing historic structures and replacing them with a new shopping mall. During the first phase of urban renewal between 1965 and 1974, six blocks of historic commercial buildings were razed but the Union Block was spared. Though most of the Union Block’s leasable spaces were occupied in this period, the building’s office core was transformed into single-room occupancy. Through a long-term lease, the dance hall, also on the second floor, became the Carlton Dance studio, which offered ballet and tap lessons to young Boise socialites between 1950 and 1980. The storefront level reflected the economic volatility of the times as tenants made bold changes in hopes of capturing a declining downtown market share. By the time of Union Block’s 1979 listing on the National Register, two of the sandstone arched bays had been shrouded in aluminum siding, and all of its original storefronts had been intensively modified.

In the 1980s, under pressure from local advocates, the city changed its strategy and embraced the preservation of downtown buildings as a key strategy of a revised renewal plan. Meanwhile, Union Block had fallen into such disrepair that the B.R.A. continued to contemplate demolishing the building. In 1995, several developers submitted proposals for re-purposing the Union Block, including one plan that called for restoring the main facade while replacing the rest of the building with a ten-story office structure. Ultimately, the B.R.A. selected a proposal by developer Ken Howell of Parklane Company, who pursued historic investment tax credits by rehabilitating the building according to the Secretary of the Interior’s standards. With the help of CSHQA Architects, Howell restored the building’s Romanesque facade and storefronts, as well as second-floor interior spaces, ballroom, and skylights to their former grandeur. Today, as John Tourtellotte originally envisioned, building users ascend the main staircase to the restored second-floor offices and ballroom to experience the surprise of daylight deep within the building’s core. The integrity of Tourtellotte’s design has been eloquently restored to serve a twenty-first-century clientele.

References

Bauer, Barbara Perry, and Elizabeth Jacox. “Union Block.” In Shaping Boise: A Selection of Boise Landmark Buildings,edited by E. Jensen and J. Austin, 24-25. Boise, ID: City of Boise, Department of Planning and Development Services, 2010.

Doty, Kay, and Don Watts. “Union Block Building.” Boise, ID: EvansGroup Technology, 1997.

Hibbard, Don, “Union Block and Montandon Building,” Ada County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1979. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC.

Ken Howell, President, Parklane Management Company LLC. Interview by Wendy R. McClure. Boise, ID, March 4, 2015.

Meredith, Neil J. Saints and Oddfellows: A Bicentennial Sampler of Idaho Architecture. Boise, ID: Boise Gallery of Art Association, 1976.

Webb, Anna. 150 Boise Icons: To Celebrate the City’s Sesquicentennial.Boise, ID: Idaho Statesman, 2013.