Designed and built in 1893, the year that Frank Lloyd Wright left the office of Adler and Sullivan, the unified regularity of the front or west facade of the William Winslow House contrasts with the exploding forms of the rear or east facade, an appropriate dichotomy for a moment of transition in Wright’s design life. Set on a level site in suburban River Forest, two miles west of Wright’s own residence (1889), the house has a broad, overhanging roof that casts deep shadows on the rectilinear, two-story west facade. The darker second-story emphasizes the separation of the hovering roof from enclosing walls, emphasizing the horizontal and indicating the roots of Wright’s Prairie Style. With golden Roman brick walls, wide, cream terra-cotta trim, and an organic brown terra-cotta frieze at the second floor, the house possesses balanced restraint and a delicacy of detail, without evoking the revivalist styles seen elsewhere in River Forest at the time.

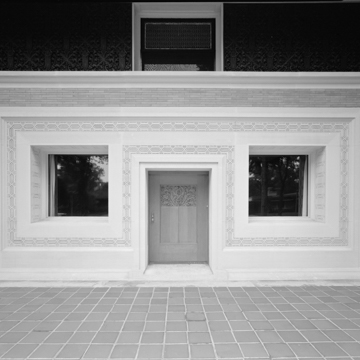

Moving past Wright’s hallmark concrete planters, visitors encounter a low porch, with a few steps leading up to the entry, centered on a wide, carved wood door, flanked by windows, and surrounded by rectilinear bands of cream terra-cotta detailing. The arched porte-cochere to the left of the house, with blooming cream terra-cotta in the pendentives, leads to the rear yard, where Wright abandons the rectilinear restraint of the front facade. A one-story hemicyclic conservatory with art glass windows of weaving caning, and a rising, rounded stair tower-chimney occupy the east facade, a powerfully dynamic composition of curving masses that defies the tight edges and right angles of the front facade, calling to mind Henry Hobson Richardson’s Glessner House (1887).

Entering through the main doors of the house, it becomes clear that Wright loosened the tight boundaries of the box in plan as well as in elevation. Opposite the entry, a carved wood arcade defines the cozy inglenook within the entry hall. Wide pocket doors allow the library, reception hall, and living room to function as a single, flowing space, while varied figurative crown moldings differentiate the rooms. A few steps and a narrower open doorway set the dining room and conservatory off from the main suite of public spaces, distinguishing the Winslow House from the more consciously unified Prairie School residences of the next decade. Wright also designed a stable at the rear of the site. In that structure, deep overhanging eaves and stucco wall planes suggest Wright’s Prairie Style vision nine years before the Heurtley House marked the maturity of his approach.

Client William Winslow owned an ornamental iron-working company and a small publishing company, Auvergne Press. A client of Adler and Sullivan, he offered Wright the commission because Adler and Sullivan were not interested in residential work at the time. Wright included the Winslow House in his 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio, editing the images to retroactively emphasize the Prairie Style aspects of the design. Subsequent owners of the Winslow House have made some minor changes to the property, enclosing and enlarging a rear porch and converting the stable into a garage. Wright’s first major independent commission, the Winslow House remains a private residence that embodies a transitional moment in Wright’s career.

References

Brooks, H. Allen. The Prairie School. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. In the Nature of Materials: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, 1887–1941. New York: Da Capo Press, 1942.

Secrest, Meryle. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.