On the outskirts of Louisville is Norton Commons, a planned community in which the concepts of New Urbanism and Traditional Neighborhood Development are put into practice. Developers Charles Osborn and David Tomes approached arts advocate Mary Norton Shands with the idea of developing 595 acres of her farmland, inherited from media developer George Norton, as a mixed-use community. Shands then formed the Norton Trust and in 1997, invited planner Andres Duany to hold a weeklong charette with local architects, planners, and neighbors. Although Norton Commons is related to Duany and Elizabeth Plater Zyberk’s plans for Seaside and Celebration in Florida, it looks as well to the nineteenth-century planned neighborhood of St. James and Belgravia courts in Old Louisville.

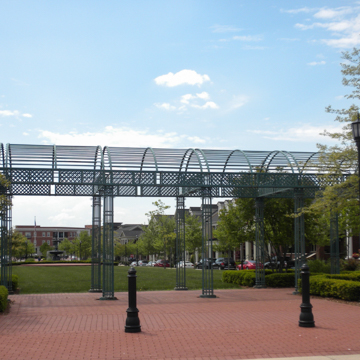

The resulting master plan responded first to the needs of the locale for efficient water runoff; 150 of the 595 acres of farmland were set aside for parks and green space, the bioswales of which take the water down to nearby Harrods Creek, Hite Creek, and Wolf Pen Branch. The community is being developed incrementally, beginning with the area south of an oval community green at the center of the acreage. Oval Park leads directly to the Meeting Street Park greensward; its arrangement is inspired by Louisville’s Central Park and the house-lined greensward of St. James Court, with the choice of the tiered central fountain being especially telling.

Employing the language of nineteenth-century planners, Norton Commons is divided into three concentric zones: Village Center surrounds Meeting Street Park and includes retail and business concerns and multi-family dwellings as well as single-family attached and detached dwellings; Village General includes the entire southern development with attached family dwellings facing the green, detached single-family dwellings facing the streets, and multi-family dwellings at corners; Village Edge includes larger single-family dwellings with carriage houses.

Included in the master plan for Norton Commons is land set aside for infrastructure, including fire stations and schools, to be built over time. Saint Bernadette Catholic Church and Saint Mary Academy, both designed by Voelker, Blackburn, Niehoff Architects, are sedate, traditional brick buildings. Like the houses to be developed north of Oval Park, both of these buildings include geothermal heating and cooling systems. Louisville architects Luckett and Farley designed the YMCA on donated land, with a gymnasium shared with the public school built next door in 2015.

Architects and builders are selected from a pre-approved list of “guild” members. Brick commercial buildings inside the Village Center are related in scale and style to those of downtown Louisville, albeit without the cast-iron facades for which the city is famous. While the houses are all traditional in style, with examples of Colonial Revival, Victorian, and Craftsman, their uniform setbacks, large scale, and open plans make it obvious that this is a twenty-first-century, upper-class planned community. As a rule, single-family dwellings have porches while multi-family dwellings have stoops; all garage doors face alleyways, one of the defining features of Louisville, as noted by local writer Grady Clay.

Norton Commons is not a gated community and is easily accessible from the Interstate 71 and local roads. Its bucolic surroundings are rapidly being diminished by the urban sprawl of cookie-cutter subdivisions, mega-churches, and big-box stores, making Norton Commons something of a refuge for those seeking a slower, more pedestrian lifestyle.

References

Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Robert Alminana. New Civic Art: Elements of Town Planning. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2003.

Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Jeff Speck. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream.New York: North Point Press, 2001.