You are here

The Hermitage Mansion

One of the most famous residences in America, The Hermitage Mansion was the seat of a large antebellum cotton plantation located in the rural countryside just east of Nashville. Constructed in three phases between 1819 and 1837, the Greek Revival mansion was the home of Andrew Jackson from 1821 until his death in 1845, including his two terms as U.S. president from 1829 to 1837. During Jackson’s tenure, The Hermitage plantation was also home to Jackson’s family and more than 160 enslaved people.

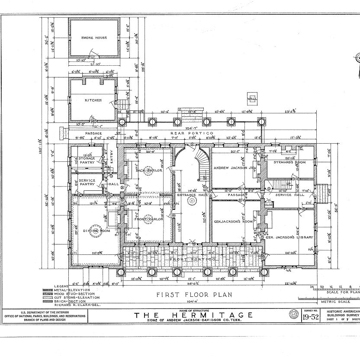

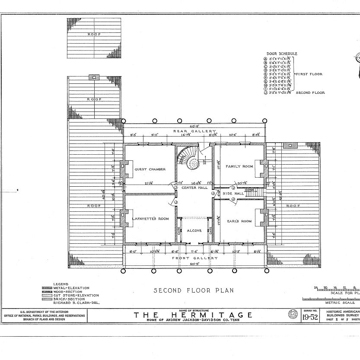

Jackson purchased the plantation in 1804, initially residing in a circa 1798 two-story log farmhouse built by the previous owner, Nathaniel Hays. The house he eventually built between 1819 and 1821 is located at the end of a cedar-lined, serpentine carriage drive connecting to the main road. His original mansion was a red brick house in the Federal Style, constructed by skilled carpenters and masons from the area, with Benjamin Decker credited as the primary builder. Enslaved workers from Jackson’s planation made the bricks in kilns on site. Typical of aspiring gentleman farmers of the region and period, the house contained eight rooms, four on each floor, and two wide center halls. The first floor contained two parlors, a dining room, and Andrew and Rachel Jackson’s bedroom. Four bedrooms occupied the second floor and a summer kitchen occupied the basement. The elegant house featured nine fireplaces, an entrance fanlight, French wallpaper, and metal gutters. Around 1828, Jackson added a simple entrance portico.

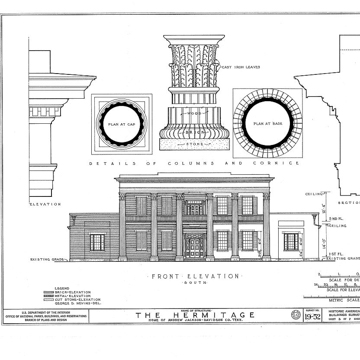

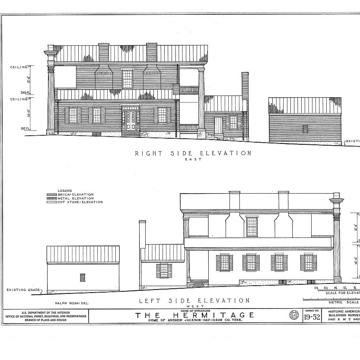

During Jackson’s presidency, the 60 x 44–foot mansion underwent a major renovation and dramatic redesign overseen by Nashville architect David Morrison, described as “Tennessee’s first architect of the Greek Revival.” In 1831, Morrison added flanking one-story wings, a two-story front portico with ten Doric columns, a small rear portico, and copper gutters. The east wing housed Jackson’s private library and a farm office. The west wing contained a large dining room and pantry. A newer kitchen and a smokehouse were also added behind the 13-room mansion, which featured a facade painted white to resemble stone. Morrison’s remodeling gave the 104 x 53–foot house a Greek Revival appearance.

Jackson also hired Morrison to design a Grecian “temple and monument” tomb for his wife, who had died in 1828. Replacing a temporary frame grave house in the garden, craftsmen completed the somber, domed monopteron in 1831–1832. A copper roof, designed by architect Robert Mills of Washington, covered the limestone tomb.

On October 13, 1834, a chimney fire heavily damaged the house and the following January, local master builders and architects Joseph Reiff and William C. Hume undertook the mansion’s rebuilding, modeling their renovation on popular pattern books of the era, including Asher Benjamin’s The Architect, or, Practical House Carpenter (1830) and The Practice of Architecture (1833). These books contained numerous examples of Greek Revival architecture, which reflected the “Grecian mania” that swept America during the Jacksonian Era of the 1830s.

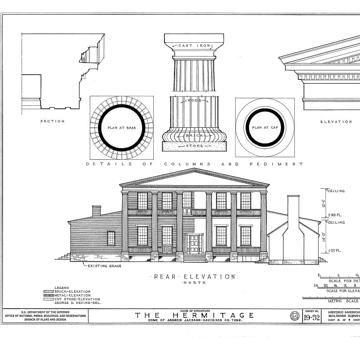

In Reiff and Hume’s redesign, the mansion’s entrance facade was transformed into a fashionable Grecian temple by adding six, two-story columns with modified Corinthian capitals featuring tobacco rather than acanthus leaves. Benjamin Latrobe had originated the idea of using this native American leaf in the capitals he designed for the U.S. Capitol in 1816. The rear entrance to The Hermitage was fitted with a gabled porch supported by six towering Tuscan columns. A “fire-proof” metal roof was installed. Tan paint mixed with sand was applied to the wooden facade and the columns to suggest stone construction.

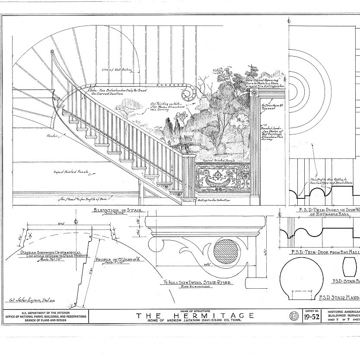

Inside the house, the builders repurposed the Federal-style woodwork by moving it into the more private family bedrooms and painting it to resemble marble. In the public rooms, including the parlors and the best guest bedrooms, Greek Revival woodwork and mantels made of Italian marble and Tennessee limestone were added. One of the highlights was the cantilevered elliptical staircase installed in the center hall to replace the original dogleg staircase.

Prior to the 1834 fire, nearly every room was covered in imported French wallpaper. Now, Jackson instructed that the damaged scenic paper be replaced in the hallways. Originally selected by Rachel Jackson, this wallpaper was created by Joseph Dufour et Cie of Paris and illustrated Fénelon’s version of the story of Telemachus and Mentor visiting Calypso’s island in search of Ulysses. Renovations were completed in May 1837.

In 1856, Andrew Jackson Jr. sold The Hermitage to the State of Tennessee. In 1889 the Ladies’ Hermitage Association (today the Andrew Jackson Foundation) opened the mansion to the public as one of the nation’s first historic site museums. Today, the 1,120-acre museum site retains not only the mansion, but other buildings dating from the antebellum period, including slave cabins, a springhouse, garden tool shed, The Hermitage Church, a formal pleasure garden originally laid out in 1819 by English gardener William Frost of Philadelphia, and the Greek Revival Tulip Grove mansion, designed by Reiff and Hume for Jackson’s adopted son Andrew Jackson Donelson. The grounds also feature archaeological remains of additional slave cabins, an icehouse, and a cotton gin.

References

Jones, Robbie D. “The First Hermitage Restoration: Historic Structures Report.” Nashville, TN: Ladies’ Hermitage Association, 2006. Report on file at the Andrew Jackson Foundation and Tennessee Historical Commission, Nashville, Tennessee.

Jones, Robbie D. “The Hermitage, Home of President Andrew Jackson: Architectural and Preservation History.” Nashville, TN: Ladies’ Hermitage Association, 2006. Report on file at the Andrew Jackson Foundation, Nashville, Tennessee.

Jones, Robbie D. “Architecture in Jacksonian America: Landmarks of American History Workshop.” Nashville, TN: Ladies’ Hermitage Association, 2005. Unpublished report on file at the Andrew Jackson Foundation, Nashville, Tennessee.

McKithan, Cecil, “The Hermitage (Home of Andrew Jackson),” Davidson County, Tennessee. National Historic Landmark Revised Nomination Form, 1978. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Maynard, Barksdale. Architecture in the United States, 1800-1850. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

Patrick, James. Architecture in Tennessee, 1768-1897. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.