You are here

Orpheum Theatre

The Orpheum Theatre is Phoenix’s last surviving movie palace and a unique example of a regionally influenced atmospheric theater design.

Constructed between 1926 and 1929, the Orpheum is a product of the building boom that coincided with Phoenix’s emerging regional status as a center of agricultural trade and commerce. In 1920, the capital surpassed Tucson to become the state’s largest city and during the following decade, bolstered by improved transportation links to the rest of the country and an emergent tourist industry, Phoenix’s population steadily increased, growing from a territorial town into a bustling American city. New subdivisions spread across the Salt River Valley and imposing civic and commercial buildings spouted downtown, including skyscrapers and movie palaces, which were both regarded as symbols of urban progress in the interwar years. The city’s first examples of a new type of opulent motion picture theaters were part of the Rickards and Nace Amusement Enterprises chain, which dominated movie exhibition in Arizona in the 1920s. Founded by Joseph E. Rickards and Harry L. Nace in 1918, the chain grew to include sixteen theaters in six Arizona cities over the next ten years, benefitting from its affiliation with Universal Pictures and the Orpheum Vaudeville Circuit. In 1926, five years after opening the city’s first movie palace, the Rialto (1921, William Curlett and Sons; demolished), the chain assembled a site at the southeast corner of Adams Street and Second Avenue for a larger theater to serve as the flagship of its growing circuit. The Orpheum’s quarter block site is located on the west end of the business district, a half block north of Washington Street, then the nexus of the city’s retail and theater district, and three blocks west of its primary north-south thoroughfare, Central Avenue. The chain retained the local architectural firm Lescher and Mahoney to design the theater alongside Hugh Gilbert, its in-house superintendent of construction who served as associate architect.

The movie palace was a short-lived type of motion picture theater that appeared in the early 1910s and declined two decades later during the Great Depression. Its genesis lies in the efforts of American motion picture exhibitors to legitimize the nascent medium of film by building large and luxurious theaters to screen movies and stage live shows in a respectable setting. The earliest movie palaces immersed Americans of all social classes in escapist environments reminiscent of European royal palaces, with immense lobbies, themed lounges, fine furnishings, museum-quality artwork, and comfortable seats—all serviced by a corps of uniformed ushers. As the type developed, movie palace design became a contest of one-upmanship as architects continually strove to dazzle novelty-loving audiences on behalf of their competing exhibitor-clients, resulting in ever more colossal, dizzyingly elaborate, and exotic theaters. The so-called atmospheric theater, popularized by the American architect John Eberson, was perhaps the most distinctive mode of movie palace exoticism, wherein the auditorium was, in essence, a permanent stage set that provided audience members with the illusion they were sitting in a courtyard beneath the night sky. Across the country, atmospheric theaters allowed American moviegoers to visit Mediterranean courtyards, Moorish palaces, and Italian Renaissance gardens for the mere price of a movie ticket.

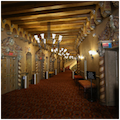

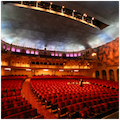

Rather than transporting Phoenicians to distant lands, Lescher and Mahoney’s Spanish Colonial Revival atmospheric theater design reflects a highly romanticized interpretation of Arizona’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century past. Located in what was a predominantly low-rise area of downtown in the 1920s, the theater dominated its surroundings. The two-story building is rectangular in plan, with the auditorium parallel to Adams Street and originally set back behind an income-producing row of ground-floor storefronts and second-floor offices; the lobbies are located behind the Second Avenue elevation. The entry is on the corner of Adams Street and Second Avenue below a three-story octagonal tower, and its elaborate Spanish Colonial Revival exterior was among the most ornate in the city. Inspired by Spanish Baroque architecture, the stucco facade is detailed to resemble stone and features an elaborate cast-stone cornice with statues of Pan, masks of comedy and tragedy, and “The Balcony of the Dons” on Second Avenue, which incorporates sculptures of conquistadors who traveled through the region. Passing through the open-air box office, ticketholders encountered an eclectic series of themed public spaces. The orchestra lobby is modeled after a medieval noble’s gallery and the mezzanine lobby recalls the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence. These ornate spaces are only a prelude to the spectacle of the 1,364-seat atmospheric auditorium, which evokes the garden of a Spanish Colonial mission at nightfall. The sidewalls recall the facades of mission buildings, with arched openings and red tile roofs, above and through which the audience can glimpse murals of Arizona landscapes painted by Phoenix artist David Swing. Other details include organ screens resembling chapel windows and a projection booth disguised as a medieval balcony. There are also wrought-iron balconies, artificial flowers and creeping vines, and a pair of bubbling fountains. Overhead, cumulus and nimbus clouds projected by concealed magic lantern machines endlessly float across the blue plaster sky while light effects produce a dramatic sunset before fading to reveal twinkling stars.

The Orpheum, alongside the Fox Phoenix Theater (1930–1931, S. Charles Lee; demolished), dominated the city’s motion picture venues into the postwar years. Typically of a movie palace, its grand opening on January 5, 1929 was a civic spectacle with a trainload of Hollywood stars and movie moguls, local politicians, and thousands of Phoenicians eager to enjoy a varied entertainment program that included the theater’s in-house orchestra, the Meisel and Sullivan organ (succeeded today by a Wurlitzer), vaudeville performers, and a talking picture. Within a few months of the opening, Rickards and Nace sold their theaters to Paramount-Publix, a Hollywood-controlled national theater chain aggressively entering the Arizona market. After its first few years in operation, and following vaudeville’s decline, the theater functioned principally as a movie house (it was renamed the Paramount in 1949), although it sometimes hosted other events. In 1968, the Nederlander Organization of New York purchased the theater for touring Broadway productions, renaming it the Palace West (after Nederlander’s Palace Theater in New York). When this venture proved unprofitable, the Organization leased the theater for Spanish language films in 1977.

By the early 1980s, theater was for sale and at risk of demolition. The Junior League of Phoenix advocated for its preservation and helped persuade the City of Phoenix to purchase the theater for use as a performing arts center in 1984. The city retained van Dijk, Pace, Westlake Architects of Cleveland to oversee a four-phase rehabilitation beginning in 1986. Ultimately, city officials incorporated the theater into plans for a new twenty-story city hall to be built on the remainder of the block. The rehabilitation included a larger stage house, additional lobby space carved out of the offices and storefronts on Adams Street, and new mechanical systems. Conrad Schmidt Studios of New Berlin, Wisconsin, restored the landscape murals in the auditorium along with other decorative details. The Orpheum reopened on January 28, 1997, resuming its historic role as a center of cultural life in Phoenix. Inside the auditorium clouds once again drift lazily across the ceiling to the delight of the audience.

References

Elmore, James W., FAIA, ed. A Guide to the Architecture of Metro Phoenix.Phoenix: Central Arizona Chapter, American Institute of Architects, 1983.

Garrison, James, “Orpheum Theater,” Maricopa County, Arizona. Arizona State Historic Property Inventory, 1984. State Historic Preservation Office, Arizona State Parks, Phoenix, Arizona.

Goodkin, Barry S. “The Orpheum Theatre Phoenix, Arizona.” Marquee: The Journal of the Theatre Historical Society of America37, no. 1 (2005): 3-11.

Irwin, Michele, and Karen Bottesch. The Orpheum Theatre. Phoenix, Arizona: Orpheum Theatre Foundation, 1997.

Luckingham, Bradford. Phoenix: The History of a Southwestern Metropolis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989.

“Orpheum Theater Opening Marks Epoch In City History: State Greets Magnificent New Playhouse.” Arizona Republican(Phoenix), January 5, 1929.

Naylor, David. American Picture Palaces: The Architecture of Fantasy. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981.

Naylor, David. Great American Movie Theaters. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1987.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.