You are here

Chemosphere House

Perched on a single concrete column, the Chemosphere is a brilliant structural solution to the problems of building on a precipitous site, one originally considered to be unbuildable. Like a tree, the building sprouts from the hill. Built in 1960, it is not only one of John Lautner’s most important projects, but is also one of the best-known houses in Los Angeles, one that represents the optimism of its time and place as much as the architect’s genius. Completed shortly before Silvertop and the Sheats (now Sheats-Goldstein) houses, the Chemosphere marks a turning point in Lautner’s career. Located off Mulholland Drive, it dramatically overlooks the San Fernando Valley as well as, through the Cahuenga Pass, the Griffith Park Observatory and the Hollywood Sign, and offers a glimpse of downtown Los Angeles.

The 19-foot-diameter, 3-foot-thick circular concrete foundation pad is embedded into the bedrock and covered with 4 feet of compacted soil. A 5-foot-diameter, 29-foot-high concrete column, with a 2-foot hollow for water supply and sewer (originally the gas and the electrical lines were to be installed here), carries the roughly 60-foot-diameter octagonal platform of steel and wood. Eight steel beams radiate from the center and are supported on eight diagonal steel braces. Short steel pieces extend these braces, past the floor level, to the underside of the window. Eight curved glue-laminated beams, supported on the extended braces and tied at the center of the house to a steel compression ring, form the structure of the roof, a structure similar to the one developed around that time (and produced by the same manufacturer) as the roof structures for the Midtown School. The saw-cut roof joists are precisely set into notches in the “glulam” beams, their spacing depending on their spans: wider spacing for the shorter spans (closer to the center of the house), tighter spacing for the longer spans (at the edge of the roof and giving lateral support to the glulams where the roof curves). This tighter spacing precisely defines the edge of the roof. None of the interior walls are load bearing.

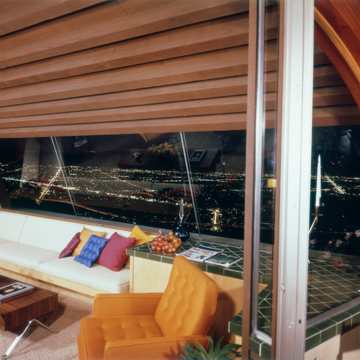

At the center, above the fireplace, is a skylight, balancing, as in other circular spaces such as the Midtown School and the Zimmerman and Hatherall houses, the light from the perimeter. A large living, dining, and open kitchen area occupies roughly one half of the house, facing north toward a view of the sprawling suburbs. The other half, facing the hill, accommodates the master bedroom, a larger second bedroom (which could originally be divided by means of a folding partition), a small third bedroom, a laundry room, and two bathrooms. It is a house suspended between the “wilderness” and the “city.” The current owner recalls watching an adventurous raccoon ambling around the wide window sills and pressing its nose against the office window, while the original owner remembers stepping into his living room one morning to find an entire human family assembled on his balcony and peering into his living room.

The house was originally designed for a young aerospace engineer, Leonard Malin, and his family. Malin had acquired the land from his father-in-law, who lived on the street below the site, where he met Lautner, who had completed the nearby Harpel House in 1956. Malin was personally involved with developing the details, mechanical systems, and construction of the house. In addition, the structure was sponsored by Southern California Gas (who supplied all appliances and heating and cooling units in exchange for the right to use the house for advertising), and Chem Seal Corporation, manufacturers of bonding, sealing, and coating compounds used in the aerospace industry and applied in the construction.

For weeks, Lautner was observed climbing around the hill, sitting and gazing at the view. At night, only the glow of a cigarette would be visible. He developed four schemes, but, unsatisfied, continued for weeks to brood over them (while the client had given instructions to proceed with one of them and waited impatiently). Lautner, the story goes, returned with his project architect, Guy Zebert, to look at what he referred to as “that lousy site,” standing at the bottom of the hill for a while before shaking his head and declaring, “there is no site.” He then pulled out an envelope from his pocket and drew the basic scheme for the house: a diagonal line indicating the slope, a horizontal line for the floor, a vertical one connecting both, and a curved line roofing over his platform. He then handed the sketch to Zebert with the instructions to “finish the drawings.” Actually, of the four schemes Lautner developed, two were fairly straightforward linear arrangements along the hill, one with a central row of supports and the other with structural arcs stapling the house to its site. In the other two schemes, Lautner had already begun to move parts of the program off the hill and onto a mushroom platform. But it was only with this visit to the site that Lautner came up with the solution to simply place the entire house on one large, freestanding structure.

Lautner was deeply fascinated by the possibilities of these mushroom structures and their economic promises. He had used similar structural concepts on other projects, beginning in 1948, though most were unbuilt. The only built project with a similar engineering concept was the Sheats (L’Horizon) Apartment Building in Westwood, structured in a series of “mushrooms,” each made up of a central concrete column supporting a 35-foot-diameter platform of radiating wood joists and held together with a steel tension ring. Following Chemosphere, Lautner continued to apply this structural strategy to settings where the logic applied. In the unrealized Alto Capistrano development, Lautner envisioned entire forests of these structures growing on the hills, leaving the hills themselves untouched. An unbuilt private house for Morris Misbin, the developer of the Alto Capistrano scheme, introduced a square variation on this idea, which is further developed in the Peters House: mushrooms, stacked as in the Sheats Apartments, reduce the structure of the house to its most elegant minimum. Floor-to-ceiling glass walls enclose what would have been an extraordinary building. The final exploration of this structural idea, with platforms assembled from pre-cast coffered slabs, occurs on the last proposed scheme for Alto Capistrano.

The Malins lived in the Chemosphere House until 1972. Following several decades of neglect, German publisher Benedikt Taschen purchased the house in the late 1990s and hired Escher GuneWardena Architecture to restore it in 1998–2000. The house remains a private residence.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.