Founded circa 1878, this early-twentieth-century mining town would not exist at its present scale had it not been for Phelps Dodge Corporation (PD), one of the largest industrial enterprises of its time and one of the largest landholders in Arizona. The prosperity PD brought to this company town between 1890 through 1915, when the copper mines were booming, is evident in Bisbee’s plethora of finely executed buildings, many designed by established architects. Despite its remote location, the town gained national notoriety in 1917 during a labor strike that resulted in the infamous “Bisbee Deportation,” during which a PD deputized posse illegally rounded up more than 1,000 strikers and supporters and transported them to New Mexico, packed in cattle cars under inhumane conditions. The town’s fortunes rose and fell with the mines, which began to dwindle when open-pit mining was introduced the 1950s. When PD finally closed the underground Copper Queen Mine in 1975, it also threatened the vitality of this mountain town. Bisbee persevered, and managed to reinvent itself as a mecca for bohemians, artists, and retirees, while also becoming a thriving as a tourist destination. Though this had much to do with its underground Copper Queen Mine tours, the town’s distinguished built fabric was an added attraction.

U.S. Army scout Jack Dunn first discovered valuable ores in the Mule Mountains in August 1877, in what was then an isolated region in southeastern Arizona Territory. The Copper Queen Mine was staked that December, and a smelter opened the following spring. As individual miners flooded into the area, an informal camp developed. It eventually took the form of a town named after Judge DeWitt Bisbee, a principal investor in the area’s burgeoning mining industry. With nearby Tombstone also growing rapidly because of mining interests, the Arizona Territory established Cochise County in 1881, with Tombstone as the seat. That same year, James Douglas, who had revolutionized ore processing in Pennsylvania, visited Bisbee and advised PD to buy the claim adjoining the Copper Queen Mine. Douglas stayed on to operate the PD’s Bisbee copper interests, which soon helped to transform the rough-and-tumble encampment into a bustling, modern town, one largely owned by the company. Incorporated in 1902, by 1916 Bisbee had a cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic population of 25,000. By then, PD had given the town a hospital, a library, a YMCA gymnasium and social clubs, a department store, a large hotel, and a town newspaper. At the turn of the twentieth century, Bisbee was supposedly the largest city between St. Louis and San Francisco.

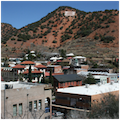

Established within Tombstone Canyon, the topography of the narrow gorge dictated Bisbee’s form. The town’s dense core is composed of contiguous two- or three-story commercial structures flush with narrow, winding streets that follow the beds of dried arroyos (periodic flooding was an issue in the town's nascent development). Buildings were integrated into the uneven terrain and steps were built where the grade was too steep. Bisbee’s urban fabric defies orthogonality and the town can rightly be called the “city of 1,000 steps.” By 1906, Main, Howell, and Brewery streets were paved in brick, and, due to severe and frequent fires, most early buildings had been replaced with masonry structures. As a company town, Bisbee was organized around segregated residential areas: the single-family bungalows and utilitarian lodging houses for bachelor miners were clustered haphazardly on narrow, terraced lots on the talus slopes or in the bottomlands; larger and higher quality residences were built onto levels cut into Chihuahua Hill on the eastern edge of town or on Quality or Higgins hills on the west. The most modest housing consisted of wood frame, adobe, or concrete block while the monumental public buildings were brick, steel, or concrete. As the town’s peak prosperity straddled the turn of the twentieth century, its buildings reflected the architectural eclecticism of the Victorian era, from Italianate to Gothic, Classical and Mission revival styles. Because Bisbee’s fortunes were tied to the price of copper, the town suffered economic hardships through the 1920s and 1930s, although a few examples of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne buildings and infrastructure projects remain from this era, including some funded by the Works Progress Administration and undertaken by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

As with any town, Bisbee displays an array of building typologies, from residential and ecclesiastical to institutional, commercial, and governmental. Most of the commerce was centered along Main Street, the entrance of which is flanked by the Second Renaissance Revival Bank of Bisbee (1904–1906) and the prominent Copper Queen Library/Post Office (1906). This building faces the irregularly-shaped “plaza” formed by the intersection of Main Street and Tombstone Canyon Road. Brewery Gulch, along Howell Avenue in the lower part of town, held lodging houses as well as brothels, saloons, and shops, the latter best exemplified in the Muheim Block (1905). The Copper Queen Hotel (1898), designed by the New York firm Van Vleck and Goldsmith, is nestled into a steep hillside along Howell Avenue as it changes direction, running east to west. Below it, at the town entrance on Tombstone Canyon Road, PD’s presence is obvious in the majestic General Office Building (1895) and the adjacent park, while the PD Mercantile (1939), a Streamline Moderne commercial building, dominates the heart of the plaza. In 1929, the county seat was transferred to Bisbee, necessitating the construction of the Cochise County Courthouse (1931), rendered in a regional Art Deco idiom by Tucson architect Roy Place. The religious diversity of the miners is reflected in buildings like St. Patrick’s Catholic Church (1916). National and regional architects worked in Bisbee in its heyday, including Goldwin Goldsmith and Joseph Van Vleck Jr. from New York; Henry Trost, a notable Southwestern designer based in El Paso; Albert Martin of Los Angeles; and Lescher and Mahoney from Phoenix. Local architect Frederick C. Hurst was also active in this period and his works still exists throughout Bisbee.

Bisbee remains a remarkably intact early-twentieth-century mining town largely because decades of economic depression preserved its initial built fabric. In recognition of its architectural heritage, its role in Arizona’s mining economy, and its notorious place in labor history, the 250-acre Bisbee Historic District and the 616-acre Bisbee Residential Historic District were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and 2010, respectively.

References

Crawford, Margaret. Building the Working Man’s Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns. Verso, 1995.

Schwantes, Carlos A. Vision & Enterprise: Exploring the History of Phelps Dodge Corporation. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2000.

Sobin, Harris, Kathryn Leonard, and William S. Collins, “Bisbee Residential Historic District,” Cochise County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 2011. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Wilson, Marjorie H., Janet Stewart, James Garrison, Billy G. Garrett, and Thomas S. Rothweiler, “Bisbee Historic District,” Cochise County, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1980. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.