Commercial telephone service using equipment licensed from the Bell Telephone Company began in the United States in 1877, and St. Louis quickly adopted the new technology. Within a year, a small group of wealthy businessmen had created a series of private lines to allow connections among themselves. The first switchboard opened in 1878 with eight subscribers in leased space in a building in downtown St. Louis at the corner of Olive and Tenth streets (now demolished).

Following patterns established by the New York Telephone Company and the Chicago Telephone Company, which moved from leased space to company-owned and designed space in the mid-1880s, the Bell Telephone Company of Missouri invested in its own telephone central office building in 1889, just a few steps from its former leased space. Investing in real estate was a major risk for the relatively young industry, and local Bell franchises tended to wait until a broad subscriber base and local conditions of competition forced the move. By 1891, when the new exchange opened at 920 Olive Street, Bell reported 2,900 subscribers. To mark the opening of the new building in February 1891, the telephone company hosted an art exhibit that welcomed the public into the company offices at street level.

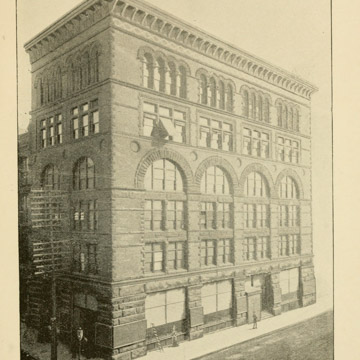

While Bell Telephone franchises tended to hire local architects to ward off public debate about the evils of national monopolies, in St. Louis, Boston-based Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge designed the seven-story red sandstone building using the sturdy Romanesque of the recently deceased H. H. Richardson. Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge had recently completed the Lionberger Building in St. Louis in 1888; the connections between native St. Louisian George Shepley and John Lionberger, who was also a treasurer of the Bell Telephone Company, certainly led to this commission.

Like the other early purpose-built telephone buildings in New York and Chicago (both demolished), the Richardsonian Romanesque style worked well for the building type, since the structural masonry piers could support the heavy equipment inside, including telephone switchboards on the building’s sixth floor and the copper wires that connected them to the building’s basement and subterranean conduits. In the late 1880s, St. Louis passed legislation requiring aerial wires for electricity, telegraph, and telephone to be buried, which resulted in the development of a sophisticated system of underground conduits that were integral to the building’s design. In addition to these industrial applications, the building also housed business offices, spaces for Bell’s traffic engineers to manage the city’s telephone network, and public space for customers to pay bills, order service, and make calls from public phones.

By 1910, the need for additional lines and switchboards forced the business office to leave the building for rented space; in 1919, the telephone company added a seventh floor. The increase in telephone use by 1920 meant that Southwestern Bell, as the company was now called, began to plan for a massive new skyscraper to replace the 1891 office. With the completion of 1010 Pine Street in 1926, S. G. Adams, a printing and stationery company, began to use the Olive Street building as its offices and retail store. By the early 1990s, Adams closed its storefront and the building remained empty for more than a decade. In 1999, the building was included on the National Register of Historic Places, and historic preservation tax credits helped fund its successful adaptive reuse into loft apartments that opened in 2004.

References

“Looking Backward.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, January 25, 1891.

Park, David G. Good Connections: A Century of Service by the Men and Women of Southwestern Bell. St. Louis: Southwestern Bell, 1984.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Company. A Monument to Communication. St. Louis: Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, 1926.

“To Go Underground.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, December 17, 1890.