Atlanta’s 189-acre Piedmont Park is one of the city’s largest and most used urban parks. Piedmont Park’s highest point, at an elevation of approximately 1,000 feet at the northwestern edge along Piedmont Avenue between 14th and North Prado streets, slopes south, east, and north to Clear Creek at about 900 feet. Within this sloping and varied landscape, the park discloses six distinct areas: the large open space of Oak Hill and the Meadow along 10th Street from Monroe Drive on the east to the apartments at the western end; Lake Clara Meer; the Active Oval, east of 14th Street, which originally served as a horse racetrack and was subsequently used as an athletic field; the Front Lawn between 12th Street and the driving clubhouse, which separates the park from the adjacent neighborhood; the Piedmont Park plateau overlooking the park, which is home to the Piedmont Driving Club and Atlanta Botanical Garden; and the Woodlands, a triangular section at the park’s north end (Piedmont Avenue and Westminster Drive) that extends to the railroad on the east and takes up about a third of the total park acreage.

The area that is now Piedmont Park began to be developed by white settlers following Indian secessions. In 1834, Samuel Walker acquired an acreage of virgin forest here, which he partially cleared for farmland and built a mill on Clear Creek. He sold the farm in 1857 to his son, Benjamin. After the Civil War, with his house and mill in ruins, Benjamin built a new farm on the high grounds, later the site of the Piedmont Driving Club. In 1868, Southern Railroad built its beltline along Clear Creek, securing a hard boundary on the east for the future Piedmont Park.

By the 1880s North Avenue was no longer Atlanta’s northern boundary due to the development of Richard Peters’s two tracts of land during the decade. Within the east tract of Peters’s land, the Peachtree Street streetcar line was extended in 1881 to Wilson Avenue (14th Street) and soon thereafter eastward to the Walker farm at the future Piedmont Park. In 1883, Edward Peters built his Queen Anne house on Ponce de Leon Avenue at Piedmont Avenue just north of North Avenue, and soon a host of other fine residences soon occupied lots along Piedmont further to the north. That same year, a group of Atlanta businessmen purchased the Walker farm in order to develop a clubhouse and racetrack.

On the Walker farmlands, the Gentlemen’s Driving Club hosted the 1887 Piedmont Exposition, which featured exhibits from Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and South Carolina, and attracted around 200,000 visitors in the nearly two weeks it operated. To accommodate the fair, the trolley lines were extended north along Piedmont Avenue and also along Monroe Drive to the southeast corner of the future Piedmont Park, which became the main entrance to the fairgrounds. A racetrack set aside by the Gentlemen’s Club became known as the Active Oval, and a road system developed around the Oval and the small lake (later Lake Clara Meer) that was created at the time of the exposition.

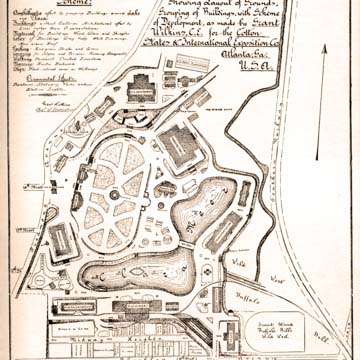

By the early 1890s, Atlanta civic leaders began to display a competitive spirit toward northern cities, especially Chicago, which had recently hosted the spectacular 1893 Columbian Exposition. Despite the recession that followed the Panic of 1893, Atlanta began plans for its most ambitious fair to date, the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, another effort to put Atlanta on the map as a destination for business investment and industrial development. Civic leaders hired Frederick Law Olmsted, who had laid out the Columbian Exposition, to develop a plan to transform the former fairgrounds into a noble civic space for Atlanta’s 1895 fair. But when the city failed to accept Olmsted’s preliminary designs, the landscape architect withdrew, and local engineer Grant Wilkins completed the site planning with Olmstedian features.

Remnants of the 1895 exposition are visible in Piedmont Park today: an enlarged lake and curving drives, terraces leading down from Piedmont Avenue, the stone retaining wall below the present athletic fields, and the staircases with rounded edging and grand stone planters preserved like archaeological relics in the upper reaches of the park. In addition to the expected agriculture, fine arts, and manufacturing buildings and the like, the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition also included a Negro Building, which celebrated African American achievements in the arts and sciences and served as a gathering place for black leaders, philanthropists, and educators. Its location at the Jackson Street entrance (now Charles Allen Drive), north of the predominantly black Fourth Ward district and Auburn Avenue, underscored the segregation at the fair and indeed, the city at large.

After the 1895 exposition, some of the monumental fair buildings were lost to fire, the athletic field returned to its earlier use for horse racing, and the lake became mosquito infested and was considered a threat to health. Though the idea to turn the land into a public park was circulated, city officials rejected it, since Grant Park had been recently established east of downtown. The lands remained an unofficial recreational area until 1904, when Edwin Ansley began to sell generous residential lots in Ansley Park, west of the exposition parklands. The Ansley Park subdivision featured curving, tree-lined streets, linear parks, and drives potentially easily connected to entries into the west end of the former fairgrounds. In order to the persuade the city that a second park was affordable, park advocates argued that neighborhoods adjacent to the several boundaries of the future park could be annexed to the city to provide tax revenue to maintain the new park; annexations were approved, city limits were extended north to include Piedmont Park, and the city bought the land in 1904.

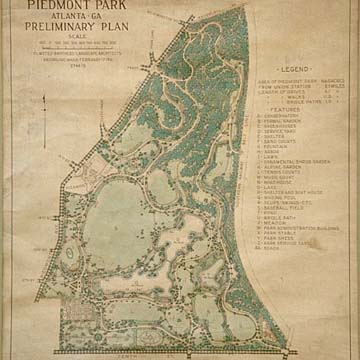

City officials hired the Olmsted Brothers to create a preliminary master plan, submitted in 1912, with the first implementation phase for parkland between 12th and 14th streets. The design linked the park to Ansley Park on the west, and beyond the open fields, on the east boundary, the firm proposed a bridge over Clear Creek (built 1916) and an underpass at the railroad tracks to link to a future suburb. Although the city failed to renew the Olmsted Brothers’ contract, which led to only sporadic park improvements during the following decades, the Olmstedian spirit may be said to inform the park in general.

The Comfort Building (1910, Harry Leslie Walker) was the first permanent structure built in the park. Further development of the park included the addition of lakeside benches and a boat house, tennis courts on the old terraces, and stone gates at the 10th, 12th, and 14th street entrances, built in the 1920s by Edwards and Sayward. This firm also designed the bathhouse (1926) and golf clubhouse (1928), the latter preserved within the larger structure of a restaurant on the corner of Monroe Drive and 10th Street.

In 1955 the Atlanta Arts Festival sponsored its second annual event in Piedmont Park, where it continued annually for decades. The famed July 4th Peachtree Road Race ended in Piedmont Park for years. Olmsted’s call for a “Little People’s Lawn” is evidenced in the children’s playground, a discrete area of the park that was further enhanced in 1976 by the addition of renowned sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s Playscapes, installed with support from the High Museum of Art. That same year, the highest grounds of Piedmont Park were leased to the Atlanta Botanical Gardens, which established its gardens and built noteworthy architecture on a site north of the Piedmont Driving Club. The Garden House, serving as a visitors’ center and entry to the botanical gardens, was designed by Anthony Ames and built in 1983–1985. Heery Architects and Engineers built the Dorothy Fuqua Conservatory in 1988–1989, and Rabun Hatch Ota Rasche added the Orchid House in 2000–2001. By this time, Smith Dalia had designed distinctive iron gates at the traditional park entrance at 14th Street, and renovated the park’s 1910 Comfort Station as a visitor’s center, both in 1996. The golf course closed in 1979, and the park was closed to through traffic in 1983, but music festivals and arts events substantially increased park usage during the 1970s and 1980s.

Increasing maintenance needs began to conflict with decreasing city budgets, resulting in a deteriorating park. In 1989, concerned citizens and civic leaders formed the Piedmont Park Conservancy, which began to take an increasing role in the preservation and development of the park. The conservancy commissioned a master plan (1994), funded off-duty policeman and maintenance workers, and sponsored additional building restorations, notably the conversion of the 1926 stone bathhouse overlooking Lake Clara Meer to Greystone, an events venue. Today, Piedmont Park remains one of the city’s most beautiful green spaces and a gathering place for thousands during the frequent special events, festivals, and exhibits held there.

References

EDC Pickering Landscapes, et al. Piedmont Park Master Plan. Atlanta, GA: City of Atlanta, 1994.

Jean-Laurent, Annabelle. “Flashback: The 1895 Cotton States Exposition and the Negro Building.” Atlanta Magazine, January 27, 2014.

Martin, Hannah. “Isamu Noguchi’s Architectural Playground in Atlanta.” Architectural Digest, September 30, 2014.

“Park History.” Piedmont Park. Accessed July 15, 2019. http://www.piedmontpark.org/.

“Playscapes.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Accessed July 15, 2019. https://tclf.org/.