Opened in 1967, Marina City presented a high-profile, architecturally evocative alternative to the suburban ideal many wealthy Chicagoans pursued in the second half of the twentieth century. The five-building downtown complex, with its expressive paired apartment towers and whale’s mouth theater presented an idiosyncratic but compelling vision of vibrant metropolitan life in miniature, prefiguring the urban renaissance of the early twenty-first century.

In 1960 Chicago posted its first ever population loss, beginning four decades of population decline for the city, as many residents of means opted for houses in outlying suburbs. Fearing the consequences of this loss, and acknowledging that the Great Depression and World War II had stalled decades of public investment in the city, Mayor Richard Daley launched a multitude of major urban redevelopment projects in an effort to draw middle- and upper-middle-class taxpayers back to Chicago, including elevated highways and large new hospital and university campuses. In 1959 William Lane McFetridge, president of the powerful Building Service Employee’s International Union (BSEIU), built on this momentum to begin planning for a major urban residential project funded by union dues. There was precedent for unions to develop residential buildings for their own members, but publicly minded real estate financier Charles Swibel persuaded his friend McFetridge that a wiser long-term investment would be an upper-middle-class residential complex that could charge rents beyond what most union members could afford.

McFetridge commissioned Bertrand Goldberg, who had designed several earlier BSEIU projects, for what was preliminarily called Labor Center. A Chicagoan, Goldberg left Harvard to train under Mies van der Rohe at the Berlin Bauhaus in tumultuous 1932. After he completed additional engineering training at the Armour Institute, Goldberg apprenticed with several Chicago firms, including the office of George and Fred Keck, known for their experimental residential work. In 1937 Goldberg opened his own office and his early work earned him a reputation for problem solving, technical expertise, and careful space planning. A founding partner of Standard Houses Corporation, from 1937 until the mid-1950s Goldberg split his energies between his firm’s small modern residential and commercial commissions and the design and manufacturing of prefabricated housing. When McFetridge engaged his services, Goldberg’s small office was designing its largest work to date—Astor Tower, a thirty-story hotel on Chicago’s north side. The exaggerated height of the ground floor, raised above the street on pilotis, emphasized the structural core and transformed it into a design element. McFetridge’s project, however, represented a significant increase in scale for the firm.

The site McFetridge, Swibel, and Goldberg selected for the project was a three-acre rail yard occupying most of the block on the north bank of the Chicago River, between State and Dearborn streets. Surrounded by warehouses, adjacency to the river was the site’s major advantage, but it lacked residential amenities, and the development team determined those must be included in the project. A summer 1959 scheme for Labor Center, now rechristened Marina City, included two round, forty-story residential buildings and a round, ten-story office building. Goldberg’s office continued to develop the scheme, and by December the design largely resembled the final project.

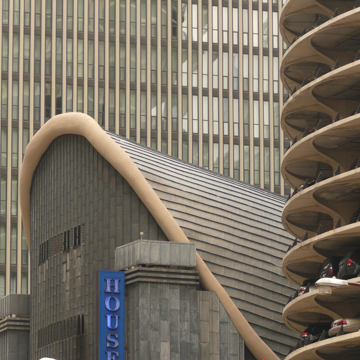

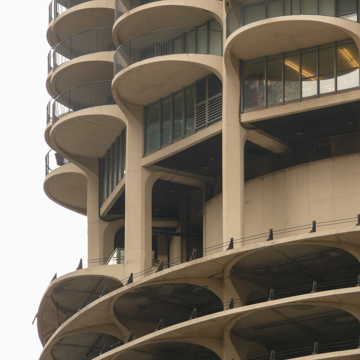

Trained as a modernist, Goldberg found in reinforced concrete a rational yet expressive material that was utterly unlike the celebrated ferro-vitreous residential buildings Mies had designed at 860-880 Lake Shore Drive a decade earlier. A marina occupies the lowest level of the site, allowing seventy boats to dock directly beneath the building. Topped by a one-story restaurant and service level, the marina serves as a platform for the entire project. The paired and rounded towers, offset along the riverbank to maximize views, are each composed of a nineteen-story open parking ramp and a tall glazed transitional story, topped by forty stories of apartments. Each bay of the towers terminates in the hemicyclic balconies that have earned the building its “corncob towers” nickname. Along the parking ramp, spaces are arranged so that cars pull to the edge of the building making them visible from the exterior. Services for each building are clustered into the central shaft, which Goldberg conceptualized as the building’s essential core, accommodating all stairs, elevators, systems, and structure. While circulation and systems are contained within this core, the structural engineers, concerned about the stability of a fully cantilevered system, added columns at the perimeter. Perceptible at the base, at the transitional level, and extending several stories above the roof, each core anchors its tower. On the residential levels, a hall rings the core to produce a round floor plan; this is divided into individual units, studios and one- and two-bedroom apartments, with acutely angled walls. Bathrooms and kitchens are clustered toward the center; at the perimeter are floor-to-ceiling glazed walls with doors leading to the rounded balconies.

At the north end of the site, visually dividing the complex from the industrial district to the north, the commercial building has a two-story glazed lower story, topped by a two-story retail and leisure zone. Finished in concrete panels, this was designed to house shops, a bowling alley, and other amenities for use by Marina City’s residents and office workers. The ten-story office building stands astride the commercial structure, on spindly vaulted concrete legs. Nestled into the center of the complex, the saddle-shaped theater roof rests on low walls, largely glazed at the entry. Walls and roof are finished with standing-seam lead panels, and oversized round cast-concrete eaves mark the transition between roof and walls.

Construction at Marina City began at the end of 1960, and once foundations were completed, an innovative climbing crane allowed workers to complete one tower floor per day. The first tenants moved into the east tower in October 1962 and both buildings opened fully in early 1963. Office tenants occupied that building in late 1964, and the contractor finished construction of the theater in 1967.

Marina City commanded considerable attention when it opened. Goldberg’s office worked closely with the owners to market the commercial and residential leases, producing promotional materials and full-scale mock-ups of apartments and offices. These efforts proved successful and demand allowed the owners to raise rents for both apartments and offices. Goldberg’s paired towers became immediate and enduring Chicago icons, appearing in countless articles and ads, in the opening to CBS’s Bob Newhart Show (1972–1978), the movie The Hunter (1980), where a car famously plunges from the parking ramp into the Chicago River, and on the cover of Wilco’s album Yankee Hotel Foxtrot (2002).

In the last decades, minor changes have done little to alter the appearance of Marina City. In 1977 the apartments were sold as condominiums; in 1994, the office tower was converted into a hotel and a restaurant was built on the site of the ice skating rink at the southeast corner of the complex. The scale, complexity, and audacity of the architecture at Marina City proved Goldberg’s skill and unique vision, and he went on to design such major complexes as Boston’s Affiliated Hospitals (1964–1971), the Chicago Housing Authority’s Raymond Hilliard Homes (1963–1966) and Chicago’s Wilbur Wright College (1986–1992). From cylinders to clover leafs to pyramids, Goldberg’s designs defy the street grid and enclose complex programs and technical requirements in dramatic concrete forms. Among Chicago’s most significant late-twentieth-century architects, Goldberg pushed the Miesian modernism in the direction of a more personal and gestural architectural expression.

References

Benoit, Michelle. “One Architect, Three Approaches: Bertrand Goldberg’s Early Experiments with Prefabrication, 1937-1952.” MAS Context. Accessed 1 May 2016. http://www.mascontext.com.

Condit, Carl. Chicago 1930-1970: Building, Planning and Urban Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

G. Goldberg and Associates. Bertrand Goldberg: Chicago Architect, 1913–1997. Accessed May 1, 2016. http://bertrandgoldberg.org/.

Marjanovic, Igor, and Katerina Ruedi Ray. Marina City: Bertrand Goldberg’s Urban Vision. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010.

Ramsey Historical Consultants. Marina City: Draft Preliminary Summary of Information Submitted to the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. July 2015.

Sharp, Robert V. and Elizabeth Stepina eds. 1945: Creativity and Crisis: Chicago Architecture and Design of the World War II Era. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.