Located south of downtown, just blocks from the Prairie Avenue residences of Chicago’s richest families, the Gothic Revival Second Presbyterian was designed in 1874 by architect James Renwick. Today it boasts one of the country’s finest Arts and Crafts church interiors, following its renovation after a fire in 1900.

Renwick designed two buildings for the congregation. The first Gothic Revival church, one of the earliest Chicago buildings in that style, was erected in 1847 on the northeast corner of Washington and Wabash; it had already proved too small for the rapidly growing congregation when it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871, one week after the last service was held there. By this time, the congregation’s downtown neighborhood had become increasingly commercial, and members had planned to relocate their church to the growing residential districts to the south. Renwick’s second Gothic Revival church for the congregation, on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Twentieth Street (now Cullerton), was built of the same local, buff dolomitic limestone as its predecessor. Corner towers and a central rose window marked the main facade. A fine collection of stained glass windows by leading artists, including Louis Comfort Tiffany and Edward Burne-Jones, indicated this was a well-funded and sophisticated congregation. The paired windows of St. Cecilia and St. Margaret by Burne-Jones (and manufactured by the William Morris Company) were one of very few examples of the British designer’s work in the Midwest. Their painted clear glass and bright jewel-toned panes reflect the medieval tradition and the hand-worked preoccupations of the British Arts and Crafts movement.

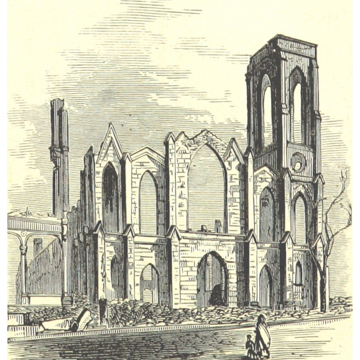

On March 8, 1900, a major fire consumed the interior of Second Presbyterian, leaving only the stone perimeter walls standing. This time, the community hired one of its own members, young architect Howard van Doren Shaw, to undertake the reconstruction. Shaw, son of a wealthy dry goods merchant, had studied at Yale and trained in architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1891, at the age of 22, he began work for Jenney and Mundie, learning their metal-framing techniques as the office worked on the Horticultural Building at the Columbian Exposition. A year later he departed for a grand tour of Europe, spending several months in England, where he encountered the domestic architecture of Charles Voysey and Edward Lutyens, leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement. Upon his return, Shaw opened his own architectural office.

Shaw fashioned the Second Presbyterian Church interior in the Arts and Crafts style, retaining the outside walls while redesigning the roof and fenestration in order to create a more horizontal and open container, which he filled with intricate, finely wrought Arts and Crafts stained glass windows, murals, and woodwork. The reconstruction of Second Presbyterian marked a turning point for the Arts and Crafts, and Chicago became a major center for the movement.

In reconstructing the Second Presbyterian, Shaw lowered the window sills in the surviving masonry walls, transformed the rose window into a round-headed one, and rebuilt the roof at a shallower pitch, lowering the proportions of the nave and drawing more light into the space. The upper balcony, wrapping around three sides of the space, now protruded beyond the side aisles, bringing movement into the space. Shaw hired a team of talented artists and artisans to create an Arts and Crafts jewel box within the re-proportioned nave. Frederic Clay Bartlett, another scion of Chicago wealth, undertook more than a dozen wall paintings and murals at Second Presbyterian—his first major commission. Similarly influenced by the British Arts and Crafts, Bartlett’s murals, including the massive Tree of Life that covers the rear wall of the altar, are in a pre-Raphaelite style, with an elegant choir of gilded, two-dimensional angels processing over a wooded landscape, with arcing rainbows following the pitch of the ceiling above. Four gilded plaster angels, designed by Carl Beil and Max Mauch, stand atop the double-height, carved wood altar screen, while cosmic lighting fixtures by William Lau illuminate the music loft. Many of the carved wooden elements, including the pews, were designed by the A.H. Andrews Company, who also executed work for the Pullman Palace Car Company.

The natural light illuminating the nave was filtered through a remarkable collection of stained glass windows. The Burne-Jones windows and one Tiffany window survived the fire, and eight more Tiffany windows were installed in the church, including the large Pastoral, which, unlike Burne-Jones’s clear panes, uses tinted and shaped pieces of glass to depict a wooded scene. Louis Millet, Louis Sullivan’s art glass collaborator, contributed some windows, as did his student, William Fair Kline, who created the new east end window. Frequent Prairie Style collaborators Giannini and Hilgart and McCully and Miles also designed and executed windows for the building. Created between 1871 and 1925, Second Presbyterian’s windows reflect more than a half century of stained glass design, executed by some of the field’s masters.

Second Presbyterian remains an active congregation. The Friends of Historic Second Church, a preservation group, offers regular tours of the church.

References

Burian, Susan Baldwin, and MacRostie Historic Advisors, “Second Presbyterian Church,” Cook County, Illinois. National Landmark Nomination Form, 2012. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Couldry, Vivien. The Art of Louis Comfort Tiffany. London: Bloomsbury Publications, 1989.