Of international importance, Greenbelt is an extraordinarily complete example of a “greenbelt town” planned and built by the federal government. Economist Rexford Guy Tugwell proposed developing model communities and resettling rural and urban families when appointed head of the Department of Agriculture’s new Resettlement Administration (RA). Of the three pilot projects, Greenbelt is the least conventional in its planning and design and the most fully realized. Greenbelt exhibits the basic features of the ideals promoted by urban planner Clarence Stein and the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA), including groupings of residential buildings with access to communal green space, main transportation arteries for automobiles pushed to the edges of pedestrian-oriented superblocks, and centrally placed nodes of community facilities.

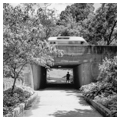

At Greenbelt, planner Hale Walker created a crescent-shaped layout with a school, commercial center with movie theater, and recreation facilities clustered at the middle. Four-story apartment buildings were placed adjacent to this area, with groups of modest row houses beyond. The two main automobile axes, Crescent and Ridge roads, join at their north and south ends to form a continuous loop. Pedestrian paths leading from residential areas to community amenities were routed through underpasses to minimize the hazard of crossing streets. Attached houses in rows of two to eight units were situated to face communal courts on their “garden side.” Services such as garages, parking lots, and trash bins were located around the outside of each grouping.

Greenbelt’s architects designed a variety of simple, efficient structures inspired by Ernst May’s avant-garde German housing estates, with contemporary streamlined flourishes. The row houses, available in two-, three-, or four-bedroom units, include a more traditional brick veneer gable-roofed model and a concrete block, flat roof variation. Bands of raised brick at the corners—now affectionately called “speed lines”—added visual interest at minimal cost. The Greenbelt Museum (10B Crescent Road) presents a representative two-bedroom, attached garage, concrete block unit as a house museum complete with the original Scandinavian modern furniture and electric appliances. The apartment buildings shared the streamlined look and materials of the concrete block houses and included large areas of glass block at the entrances.

The Moderne aesthetic extends to Greenbelt Center School (now Greenbelt Community Center; 15 Crescent) which features glass block, angular fluted fins, and curving corners. The stylized bas-reliefs by sculptor Lenore Thomas on the front elevation depict scenes representing the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution. The commercial area now known as the Roosevelt Center (107–131 Center-way) includes two streamlined concrete and brick veneer buildings housing shops, offices, and a movie theater flanking a plaza featuring Thomas’s stylized Mother and Child sculpture. A pedestrian underpass provided access to the plaza from the residential areas on the other side of Crescent Road.

The original residents of Greenbelt were chosen for their limited means and willingness to create and join cooperative community organizations. Only white families were eligible. When the federal government decided to sell in 1952, residents formed a cooperative to purchase the original houses, some of the apartment buildings, and over a thousand additional wood units added as defense housing during 1941–1942. Later decades of development have expanded the city of Greenbelt, but the original New Deal community, now a National Historic Landmark district, maintains its cohesive plan and cooperative community structure.

References

Gournay, Isabelle, and Mary Corbin Sies. “Greenbelt, Maryland.” In Housing Washington: Two Centuries of Residential Development and Planning the National Capital Area, edited by Richard Longstreth, 203-228. Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, 2010.

Knepper, Cathy D. Greenbelt, Maryland: A Living Legacy of the New Deal. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Lampl, Elizabeth Jo., “Greenbelt, Maryland Historic District,” Prince George's County, Maryland. National Historic Landmarks Nomination Form, 1996. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.