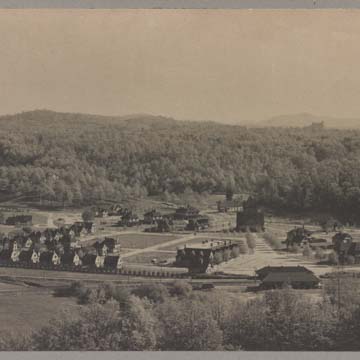

Biltmore Village was the model village designed to house the workers employed at George W. Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate. To construct the village, Vanderbilt acquired the entire settlement of Asheville Junction, located on the south bank of the Swannanoa River about a mile from where it joins the French Broad River, and relocated its residents. Also known as the town of Best, the site featured a railroad stop two miles from the center of Asheville and near the entrance to the estate. Vanderbilt constructed a spur from this railroad line to transport workers and materials to Biltmore. The village was laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted and its buildings were designed by Richard Morris Hunt and Richard Sharp Smith. This new village would provide the first impression of Vanderbilt’s estate to visitors arriving by train.

Olmsted planned the village in a fan-shape, and located the most important building, All Souls Cathedral, at the pivot. He aligned it with the railroad station on the other end of the site to north. In front of the station was a central plaza that served as the commercial center with a post office, hospital, and shops. Of the buildings designed by Hunt, All Souls, the Parish House, the railroad station, and the Biltmore estate office are still extant. The architecture was largely medieval and picturesque, with rough pebble dash, red brick, and/or Tudoresque half-timber walls, steeply pitched roofs, multiple gables, dormers, and recessed porches. Hunt’s son, Richard Howland Hunt, continued the designs after his father’s death in 1895.

Richard Sharp Smith, who was brought to Asheville by Hunt to supervise the Biltmore House construction, continued designing cottages for the village into the early 1920s. More than a dozen of his one-and-a-half to two-story cottages survive, as well as a handful of other structures. Smith continued to work for Vanderbilt for six years after Hunt’s death and later opened his own practice in Asheville. As a result, the architecture of Hunt and Smith served as a significant precedent for much of what was built in the area during the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The village suffered significant damage from a devastating flood in 1916. In 1920 civic and business leader George Stephens purchased Biltmore Village for resale to individual buyers. By midcentury, with the incursion of fast-food chains and parking lots, among other modern assaults, the village’s historical integrity was compromised. In 1979, to help preserve its character, Biltmore Village was designated a historic district on the National Register; it has a local historic district designation as well. Biltmore Village is now a commercial hub with numerous restaurants, boutiques, and galleries. Its residences include condominiums in addition to the historic single-family houses.

References

Bishir, Catherine W. North Carolina Architecture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Bishir, Catherine W., Michael T. Southern, and Jennifer F. Martin. A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Hansley, Richard. Asheville's Historic Architecture. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2011.

Roth, Leland. “Hunt, Richard Morris (1827-1895).” North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary. North Carolina State University Libraries, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2019. http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/.

Smith, McKelden, “Biltmore Village Historic Resources,” Buncombe County, North Carolina. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1976. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Swaim, Douglas. Cabins & Castles: The History and Architecture of Buncombe County, North Carolina.Asheville: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1981.