Delaware Park

The focal point of Olmsted and Vaux’s masterplan for the Buffalo park and parkway system was a 350-acre parcel on the northern outskirts of the city notated in Frederick Law Olmsted’s drawings as "The Park." The largest of three sites pre-selected by the city’s Board of Park Commissioners in 1866, the park abuts the picturesque rural cemetery of Forest Lawn (1850) to the southwest and the Olmsted-designed streetcar suburb of Parkside (1880s) to the north and east. To the west of the park are the landscaped grounds of the New York State Asylum for the Insane, designed by Olmsted in conjunction with architect Henry Hobson Richardson in 1871. In Olmsted’s view, these contiguous greenspaces, both public and private, provided a naturalistic refuge from the surrounding city. The renamed Delaware Park eventually grew to 376 acres and is today enveloped by more than a century of urban growth. Always considered the crown jewel of Buffalo’s park system, The Park was selected as the site of the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, during which President William McKinley was assassinated by anarchist Leon Czolgosz.

The Park reflects the naturalistic design elements of the English landscape garden tradition, and was conceived as a pleasure ground for passive recreation. Olmsted divided the large parcel into two distinct areas: on the east, a 243-acre pastoral “meadow park” in which an open, 120-acre field was ringed by copses of mature deciduous trees and a meandering perimeter road; on the west, a 133-acre “water park” with a 46-acre lake. Olmsted’s plan reserved the northeastern corner of the meadow for the Farmstead, a deer paddock and sheep pen that was transformed into the Buffalo Zoological Gardens in the 1890s. Scajaquada Creek, which courses naturally through the western end of the parklands, was widened to form Mirror (now Hoyt) Lake and Gala Waters, a small bay. In 1886, 12 acres on the park’s southern edge were donated in memory of local businessman and park commissioner Dexter P. Rumsey. The following year, Olmsted designed a picturesque ramble within the parcel’s densely canopied ravine. With this addition, the park’s tripartite landscapes of meadow, forest, and lake offer a conceptual and stylistic parallel to the scheme Olmsted and Vaux employed in New York’s Central Park (1857).

The park’s earliest carriage route, designed by Vaux in 1874, was the north-south pleasure drive of Delaware Avenue, which bisected the park. Located in a depression in the site’s natural topography, the avenue allowed for easy grade separation via a large stone viaduct. As in Central Park, Delaware Avenue allowed pedestrian and carriage traffic to intersect safely. Bridle paths provided a third, separate circulation system and landscaped parkways extended out from Delaware Park, bringing nature into the existing urban grid. These tree-lined parkways punctuated by public squares connected The Park to The Front and The Parade, subordinate parklands located four miles away, to the southeast and southwest, respectively.

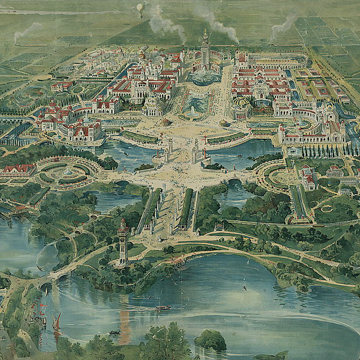

Vaux designed a number of facilities for the park, including a boathouse (1875), the “Spire House” gazebo (1875), and a dwelling for the park superintendent (1875). Many of Vaux’s structures were demolished in anticipation of the Pan-American Exposition, including the Stick Style wooden boathouse razed in 1900 to make way for a three-story masonry structure designed by local architect Edward B. Green. The park as a whole was extensively remodeled for the exposition with building ensembles whose Beaux-Arts–inspired compositions and classically derived architectural details were reminiscent of the Court of Honor at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Streets were laid in the park’s interior and the lake was transformed into a “Venetian lagoon,” complete with gondolas and a fountain. An iron bridge over the Gala Waters, a replication of Vaux’s original 1874 bridge, was replaced with a marble span flanked by plaster lions. Most of the buildings erected for the Pan-American Exposition were timber or steel-frame structures with precast plaster panels; these were meant to be temporary and were razed by March 1903. The permanent buildings included Edward Green’s Fine Arts Pavilion (1905), a neoclassical design that was not completed in time for the exposition and is now the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and George Cary’s New York State Pavilion (1901), which now houses the Buffalo History Museum. In 1914, the Parkside Lodge was erected near the zoo. Designed by James Walker in an Arts-and-Crafts style, the lodge served as a locker house and lounge for athletes using park facilities.

In the first quarter of the twentieth century, what remained of Olmsted’s original design after the exposition was altered for active recreation facilities. A nine-hole golf links encroached on the quiet tranquility of the meadow circa 1912; by 1930, the links were expanded to an 18-hole course. Open areas in the park’s eastern half were dedicated to organized sports, including four baseball diamonds, tennis courts, and soccer fields. The zoo was extensively remodeled between 1938 and 1942 as part of a Works Progress Administration project. Vaux’s Spire House and caretaker’s cottage were lost in the 1950s. Today, various ancillary structures from later decades dot the landscape. The biggest intrusion into the park landscape was, and remains, the Scajaquada Expressway, completed in 1962. Formed from the earlier, Olmsted-designed Scajaquada Parkway and Humboldt Parkway, this east-west state highway bisects the park laterally. Although Congress for New Urbanism and other planning advocates have called for the highway’s removal or downgrading, it remains in place, a vivid reminder of the way urban parks were compromised by what passed for progress in a different era.

References

Broderick, Stanton M. “Buffalo’s Olmsted Parks and Parkways System.” Olmsted in Buffalo. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.olmstedinbuffalo.com/.

Kowsky, Francis R., ed. The Best Planned City: The Olmsted Legacy in Buffalo. Buffalo: Burchfield Art Center, 1992.

Kowsky, Francis R. “Municipal Parks and City Planning: Frederic Law Olmsted’s Buffalo Park and Parkway System.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 46 (March 1987): 49-64.

Rogers, Elizabeth Barlow. Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001.

Ross, Claire L., “Olmsted Parks and Parkways Thematic Resources,” Erie County, New York. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1982. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Kowsky, Francis R. “Municipal Parks and City Planning: Frederic Law Olmsted’s Buffalo Park and Parkway System,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 46 (March 1987): 49-64.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.