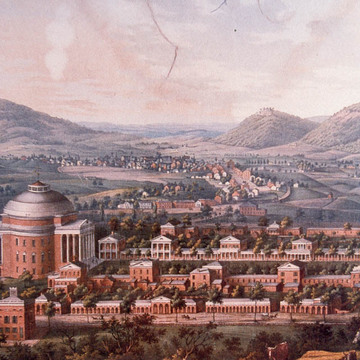

Jefferson's original campus, the Academical Village surrounds the space known as the Lawn and comprises the Rotunda, the pavilions, dormitories, and ranges. Ground was broken on “a poor old turned out field” west of the small town of Charlottesville on October 6, 1817. Jefferson selected the site atop a small ridge, which was subsequently leveled into terraces. The site caused Jefferson to modify an earlier (1814) scheme (a vast U-shaped plan nearly 300 yards across with three pavilions to a side) into a plan with two parallel rows 250 feet apart consisting of five pavilions on each side. From the beginning Jefferson intended that professors would live on the upper floors of the pavilions and give instruction on the ground floor. Between the pavilions, fronted by a Tuscan colonnade, lay dormitory rooms for the students, who were originally housed two in a room. The concept of a large central building serving as a library was added in 1817. Jefferson wanted to create an “academical village” where the students would live near their professors and their classes and would be shielded from worldly temptations. Although the concept was largely Jefferson's, he requested advice from William Thornton and Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Thornton's hand is discernible in the facade of Pavilion VII, and Latrobe influenced the Rotunda and several of the pavilions. He recommended the giant orders, and the facades of pavilions III and V closely follow his concepts. Pavilion IX is apparently his design—or at least Jefferson so noted it on his drawing.

The details of the facade of each pavilion represent different antique models found in two books Jefferson consulted, Giacomo Leoni's The Architecture of A. Palladio (1742) and Roland Fréart de Chambray and Charles-Edouard Errard's Parallèle de l'Architecture Antique avec la Moderne (1766). Jefferson explained that the pavilions should “be models of good taste and good architecture, & of a variety of appearance, no two alike, so as to serve as specimens for the architectural lectures.” The pavilions' orders and sources are: (I) Doric of Diocletian's Baths, Rome, from Chambray; (II) Ionic of the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, Rome, from Palladio; (III) Corinthian from Palladio; (IV) Doric of Albano, from Chambray (though Jefferson added a base); (V) Ionic from Palladio; (VI) Ionic of the Theater of Marcellus, Rome, from Chambray; (VII) Doric from Palladio; (VIII) Corinthian of Diocletian's Baths, Rome, from Chambray; (IX) Ionic of the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, Rome, from Palladio (originally Jefferson intended Tuscan, but altered it in construction); (X) Doric of the Theater of Marcellus, Rome, from Chambray. For the Rotunda (inspired by Latrobe's suggestion and by drawings that have been lost), Jefferson turned to the Pantheon in Rome as shown in Palladio.

Additional student housing was provided in the outer ranges, which were articulated by arcades and had larger structures—called hotels—at the ends to serve as centers for eating. Gardens separated the pavilions and ranges and were enclosed by curving—or serpentine—brick walls. In 1952 and 1965, with funds provided by the Garden Club of Virginia, the west garden walls were restored and “colonial”-type gardens created after designs by Alden Hopkins. In 1965 the Garden Club paid for the east garden walls and gardens designed by Donald E. Parker and Ralph E. Griswold.

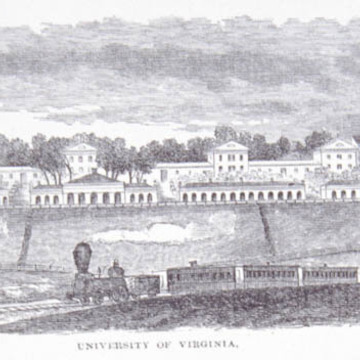

Jefferson produced most of the drawings for the project, though John Neilson assisted him in an attempt to produce prints that could be sold to raise funds. Neilson drew the widely reproduced “Maverick Plan” (named for the engraver), c. 1822, and many of the drawings that for years were attributed to Jefferson's granddaughter, Cornelia Jefferson Randolph. Recent research indicates that Neilson was the author. The university was one of the largest single projects undertaken up to that point in the United States, under construction from 1817 to 1826. Jefferson supervised the initial stages of construction, but he found the task too much for his age, and ultimately a “proctor” was hired to oversee the project. Jefferson also designed the curriculum and selected the library and the faculty.

Jefferson intended that the entrance to the complex be at the south, or open, end, with an approach up the central space toward the Rotunda. The trees that line the space were initially planted c. 1830 and have been replaced many times. Whether Jefferson intended the trees is hotly debated; several of his early schemes indicate grass and trees, and the university did purchase live trees before his death. Since the early 1980s the university has embarked on an ambitious restoration program for the Lawn (J. Murray Howard, restoration architect). Pavilions VIII and X display Jefferson's original tin roofing.

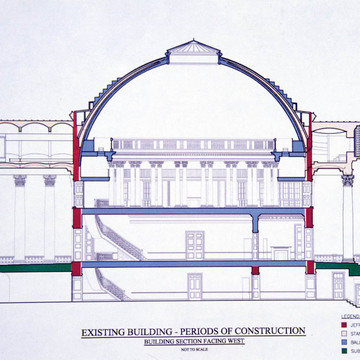

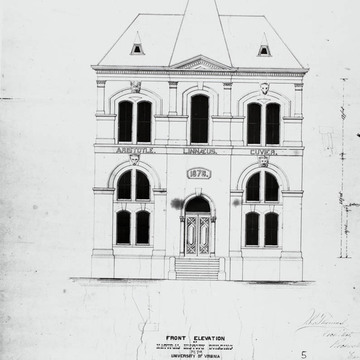

Robert Mills designed the Annex, constructed on the north side of the Rotunda in 1853. Brooks Hall (1876–1877, John R. Thomas), to the east of the Rotunda, is a Second Empire structure with carved animal heads (including a tapir!), which originally housed a natural history museum. The names and heads on the building represent a theory of natural history, a radical concept for a southern school in the 1870s and probably not understood (Thomas came from Rochester, New York). Brooks Hall is balanced to the west of the Rotunda by the Gothic Revival University Chapel (1884–1890, Charles E. Cassell). J. & R. Lamb and Sons provided most of the opalescent window glass for the chapel, except for the mandorla in the east transept, which is by Tiffany Studios (c. 1905). The chapel attempted to answer the charge of heathenism at the university, since Jefferson had specified no chapel. The location of the chapel and Brooks Hall along the sides of the Rotunda and adjacent to the major east-west road indicate that most people approached the university from the north end and not from the south as Jefferson had envisioned. When an 1895 fire consumed the Rotunda and Mill’s Annex, the rebuilding of the Rotunda (the Annex was not rebuilt) reoriented the campus toward the north, with a new entrance portico and terrace on its north front designed by Stanford White.

White also designed the buildings closing the south end of the Lawn: Cabell, Rouse, and Cocke halls (1896–1898). The controversial siting of the buildings, which closed off the vista, was directed by the Board of Visitors. These structures buffered the campus from an African American neighborhood below and were part of White's plan for future expansion. Cabell Hall, with its pediment sculpture by George Zolnay, occupies the center of the new group, and its semicircular auditorium, with a large mural by George W. Breck after Raphael's School of Athens, echoes the shape of the Rotunda at the head of the Lawn. White initially participated in the design of Garrett Hall (University Commons, 1906–1908), but after his death in 1906, his New York office redesigned it. All of the sculptures in the Lawn area were installed in 1919 during a wave of campus beautification. They include Moses Ezekiel's Homer (1907); Karl Bitter's seated Jefferson (1916), which is a reduced version of a larger one in St. Louis; a copy of Jean Antoine Houdon's Washington (1913); and, on the Rotunda's north terrace, Ezekiel's Jefferson (1910), showing him perched on top of the Liberty Bell.

Subsequent buildings on the central grounds in general respect the palette of red brick with white trim and the neo-Jeffersonian Roman classicism, which is more popularly called Colonial Revival, even though Jefferson was hardly colonial. Randall Hall (1898–1899, Paul J. Pelz), originally a dormitory and now the history department, and Minor Hall (1908–1911, John Kevan Peebles), on opposite sides of White's south Lawn buildings, follow his scheme for expansion, with lateral extensions to the east and west. Boston landscape architect Warren Manning worked at the university between 1908 and 1913 and provided a new plan in 1913.

Peebles, a Norfolk architect and University of Virginia alumnus, became the favored architect for the first three decades of the twentieth century, serving as a member of the university’s architectural advisory board. The board designed many campus structures, such as Clark Hall (1930–1932, Peebles with Walter Dabney Blair, Edmund S. Campbell, and R. E. Lee Taylor), which contains murals by Allyn Cox. Now the Environmental Sciences Department, it features a mammoth portico that announces that the building originally housed the law school.

Fiske Kimball, who had a reputation as a Jefferson scholar, came to the university in 1919 to head the new department of fine arts, which principally included an architecture school. Kimball, following an earlier suggestion of Manning, designed the McIntire Amphitheater (1920–1921), which is an expression of an American mania of the 1910s and 1920s for outdoor theaters of the ancient Greek type. To the south, looming over the amphitheater, is a recent Jeffersonian interpretation, the postmodern Bryan Hall (1987–1995, Michael Graves). Graves's building provided an important cross-campus link. The columns of his Tuscan colonnade resemble milk bottles.

Edmund S. Campbell, the head of the architecture department from 1928 to 1950, took the lead after Kimball's departure as the university architect and, in association with Peebles and others, guided the university's development in the 1930s and 1940s, maintaining the red brick and white trim imagery. The Monroe Hill Dormitories (1928–1929, Campbell, Peebles, Blair, and Taylor) form a series of small courtyards. Next door is the oldest building on the campus, Monroe Hill House (c. 1790 and c. 1840), which James Monroe owned before Jefferson selected the site for the university. The arcaded wing was added to provide additional housing for students.

To the immediate north stands Monroe Hall (1929–1930, Peebles, Blair, Campbell and Taylor; 1984–1987 extension, Hartman-Cox). Originally Monroe Hall's main entrance was to the south, but Hartman-Cox of Washington, D.C., extended the building to the north and provided a fitting facade to join the other grand porticoes on a large “secondary lawn” that had grown up in the twentieth century. The Hartman-Cox addition is one of the best recent works at the university. Next to Monroe Hall to the north is the giant portico of Peabody Hall (1912–1914, Ferguson, Calrow, and Taylor), which originally served as the School of Education. Behind Peabody is the student union, Newcomb Hall (1952–1958, Eggers and Higgins; later renovations), a surprisingly awkward structure by this well-known New York firm.

The inherent problems of adding to a circular library and the university's expansion brought about a new structure, Alderman Library (1936–1938, R. E. Lee Taylor and D. K. Este Fisher, Jr.; later additions), to the west of the Rotunda and north of Peabody Hall. Designed to be the new centerpiece to the university, it had the appropriate grand colonnade and great entry space. Alderman Library's construction led to the demolition of Jefferson's last design for the university, the Anatomical Theater (1826), which originally stood in front.

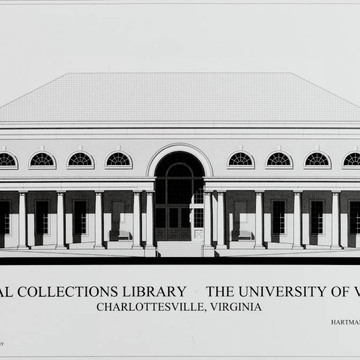

The university built a new Special Collections Library (2001, Hartman-Cox) next to Alderman on the site of Miller Hall (demolished in 2002). The entrance pavilion draws upon Jefferson's Anatomical Theater and Charles McKim's Pierpont Morgan Library (1906) in New York. Most of the library, however, is underground. Behind is the undergraduate Clemons Library (1979–1982, TAC), for which Norman Fletcher acted as lead architect. This is the only modernist intrusion on the central grounds, rendered in red brick and hidden in the hillside.

The university's central grounds encompass over 180 years of architecture and many diverse trends. The use of open space and landscaping has also changed dramatically over that time. Jefferson's original design for the Lawn still remains the central focus, and the various additions illuminate both its genius and the problems of adding to such a dominant design. Although it is fashionable to diminish all the subsequent work, the fact remains that Jefferson designed for a select community of about ten professors and several hundred students. The subsequent additions respect the original but also, in their own way, create a number of wonderful spaces.

References

Wilson, Richard Guy, David J. Neuman, and Sara J. Butler. The Campus Guide, University of Virginia. 2nd ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012.