You are here

Hampton University

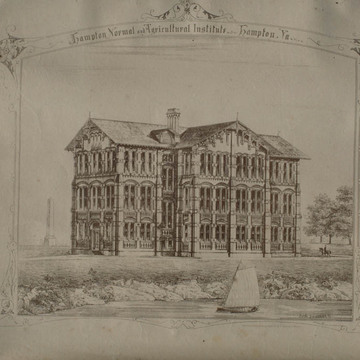

The Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was founded in 1868 through the efforts of General Samuel C. Armstrong to provide education in manual skills and teaching for newly freed African Americans and for Native Americans. Armstrong, raised in the Hawaiian Islands, had observed missionaries working among the native tribes and conceived of duplicating these efforts in the American South. During the Civil War he commanded black troops in the Peninsular Campaign and later headed the Freedmen's Bureau in Virginia. The site he selected, fronting on Hampton Creek with a commanding view of Hampton Roads, was marked by a tree known as the Emancipation Oak Tree, which had been a gathering place for freedmen after the Civil War. An old plantation house, Mansion House (c. 1820), on the property near the waterfront, served and continues to serve as the President's House. Adjacent were a national soldiers' home and a national military cemetery.

Believing that environment played a role in education, General Armstrong selected his architects with care, a tradition that has continued. The initial architect for Hampton was a New Yorker, Richard Morris Hunt, who contributed three buildings, of which two remain. The selection of Hunt, the first American to attend the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and a leader of his profession, indicates the architectural aspirations of the school. Following Hunt came New Yorkers J. Cleveland Cady and the firm of Ludlow and Peabody. In the 1940s Hilyard Robinson, a leading Washington-based African American architect, designed a number of structures that introduced International Style modernism to the campus. The initial buildings all fronted on the water, but Ludlow and Peabody, who became the campus architects in 1915, shifted the focus inland, away from the Hampton River, creating a series of loose quadrangles.

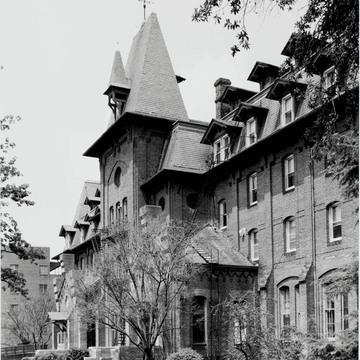

Virginia Hall (1872–1879, 1885, Richard Morris Hunt) was Hunt's second building for the campus and by far his most commanding. A giant, bristling structure of red brick with tall mansard roofs, dormers on top of dormers, heavy buttresses, and elaborate wood bracing, it is difficult to define stylistically. Certainly it displays Hunt's French training—perhaps Néo-Grec would be the best term to apply—but it escapes those boundaries, for Virginia Hall is aggressively original and was part of Hunt's attempt in the 1860s and 1870s to create a new American architecture.

Second Academic Building (1879–1881, Richard Morris Hunt) replaces Hunt's first building at the school, the First Academic Hall (1869–1870), which burned in 1879. Hunt's surviving drawings for this building (in the Prints and Drawings Collection, American Institute of Architects, Washington, D.C.) show a tower or campanile, which was eliminated during construction. Also, repainting over the years has diminished the original contrast between the revealed brick surrounds of the windows and the stucco infill panels. The large windows were a Hunt trademark derived from French studio buildings.

The Marquand Memorial Chapel (1886, J. Cleveland Cady) was a gift of the New York financier and first president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Henry G. Marquand. For this large, assembly-hall type of structure, Cady, who ran a large New York firm, followed Hunt's lead by creating a landmark with a dominating campanile. Stylistically, Cady employed the fashionable Romanesque, though his treatment did not follow the Richardson lead as much as it provided a new interpretation. The ornament deserves attention, for heads of Native Americans and Africans are cast into the brick cornice.

Ogden Auditorium Hall (1916, Ludlow and Peabody) is an impressive structure that illustrates a later stage of the BeauxArts in America, Hunt representing the earlier. Charles Peabody attended the Ecole des BeauxArts, and his New York firm was extremely prominent, both in the city and as university architects around the country. The entrance facade of Ogden Hall, with its paired Roman Doric columns, became the dominant element balancing the two Hunt buildings. The architects also attempted to mediate with a yellowtan brick and Venetian red tile roof. Other Ludlow and Peabody buildings on the campus worthy of note and remarkably consistent in style, color, and form are James and Clarke halls (1919), the Administration Building (1918), the Huntington Library (1924), and the Science Building (1928).

Davidson Hall (1954–1956, Hilyard Robinson) marks the introduction of modernism at Hampton University. Designed as a women's dormitory and with a commanding view of the Hampton River, it is a taut, redbrick-veneered volume with a clear distinction between the commons area, the stair tower, and the dormitory wing. Robinson obtained the commission through William Henry Moses,

Armstrong Hall (1960–1962, Hilyard Robinson and William Henry Moses) is in the mode best known through Minoru Yamasaki's work of the period. A cast-concrete block screen masks one elevation. The problems of designing a large container-type classroom building in a contemporary manner and fitting it into a Beaux-Arts campus are well illustrated.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.