You are here

Ellsworth Storey Residences

Ellsworth Prime Storey’s design work challenged the status quo within a growing Seattle in the early part of the twentieth century. Many of his residential works, including the Ellsworth Storey Residences, are viewed as precursors to the regional Pacific Northwest style with its emphasis on local materials and open, fluid interior spaces. Similar to his contemporaries Frank Lloyd Wright, Bernard Maybeck, and Charles F. Voysey, Storey adapted historical design ideas and styles to reflect emerging modern lifestyles across a range of building types.

The Ellsworth Storey Residences, excellent examples that demonstrate Storey’s desire to design for modern lifestyles, were completed between 1903 and 1905, shortly after his arrival in Seattle to establish his professional career. For much of Storey’s career, he maintained an active Seattle practice with commissions covering a variety of building types completed in a range of styles reflective of his clients’ requirements. These included residences, churches, and public buildings in Georgian Revival, English Neo-Gothic, Tudor, and many other building types and styles. Yet most of his residential structures, such as the Ellsworth Storey Residences, demonstrate the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement. This influence and his use of materials unique to the region are perhaps the reasons he is often identified with the origins of what later became a Pacific Northwest architectural idiom.

Storey’s Arts and Crafts architecture reflected his interest in understanding how people expected to live in and use residential space. For example, the Ellsworth Storey Residences included dedicated closet space and multiple bathrooms. By themselves, these inclusions may seem mundane, but in comparison to then popular Victorian house arrangements and contemporary high-style residential design, such spaces represented new attitudes—particularly in the early-twentieth-century Pacific Northwest. The Storey residences also explored different expectations for public-private and interior-exterior arrangements. Service and private sleeping areas remained separate from the public (or social) areas of the houses, but the semi-public spaces were connected to exterior views on multiple sides and linked together by a large, open, glass-enclosed conservatory space that served both as entry and living quarters.

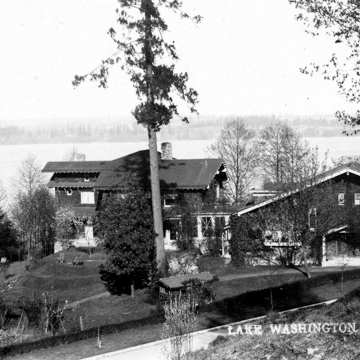

The Ellsworth Storey Residences, which have always remained private and are today difficult to see from the street, are technically two, two-story residences joined together by a conservatory. The first of these, in 1903, was completed for Storey’s parents and the other, completed in 1905, was designed for Storey himself and his soon-to-be wife. Wide angular eaves supported by wooden corbels and ridge-beam extensions highlight the exteriors of both houses, and windows feature geometric muntin patterns. The buildings are clad in black cedar shingle siding, while trim on windows and eaves is painted white. The two houses are located in a stepped configuration; their resemblance to Swiss chalets is evident.

The houses were built originally on open lots near Lake Washington in the Denny-Blaine Lake Park Addition (1901), a streetcar suburb some three miles northeast of Seattle’s central core. Development of the area was prompted by installation of an electric trolley line from the city’s core to the Madrona neighborhood on Lake Washington, just south of the Storey house site. Most houses built in the neighborhood followed the academic stylistic influences of the time, which included versions of the American foursquare house, Victorian styling, and different revival style references. The Storey residences, which differed markedly from most others in the development, are located just south of Lakeview Park, one of several neighborhood parks built as part of the area’s development and in the spirit of the Olmsted Brothers’ plan for Seattle.

References

Carr, Christine E. “The Seattle Houses of Ellsworth Storey: Frames and Patterns.” M.A. thesis, University of Washington, 1994.

Dorpat, Paul and Jean Sherrard. “Seattle Now & Then: Madrona Park – End of the Line.” DorpatSherrardLomont. Accessed August 5, 2015. http://pauldorpat.com.

Hildebrand, Grant. “Ellsworth Storey.” In Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects, edited by Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, 132-137. 2nd ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014.

Michelson, Alan. “Ellsworth Prime Storey (Architect).” Pacific Coast Architecture Database, University of Washington Libraries. Accessed August 5, 2015. http://pcad.lib.washington.edu.

Painter, Diana. “Regional Modernism on the West Coast: A Tale of Four Cities.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 31, Translation,edited by Christoph Schnoor, 773–784. Auckland, New Zealand: SAHANZ and Unitec ePress; and Gold Coast, Queensland: SAHANZ, 2014.

Steinbrueck, Victor, “Ellsworth Storey Residences (two homes),” King County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1972. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

“The 10 Greatest Homes in Seattle History: Ellsworth Storey Houses.” Seattle Metropolitan(January 2012): 48-49.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.