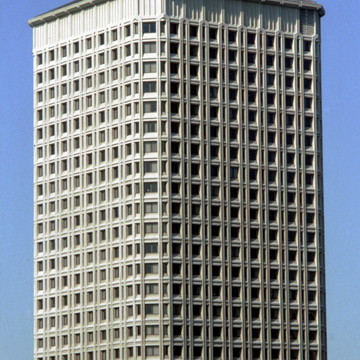

The Henry M. Jackson Federal Building, a 37-story high rise designed by the Seattle architectural firms of Fred Bassetti and Company and John Graham and Company with adjoining steps and plaza by Richard Haag Associates on the northeast edge of Seattle’s Pioneer Square, was planned, designed, and built at a time of general social upheaval from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s. The tower’s overall design could be read within this context: its precast concrete paneled exterior, chamfered corners, concrete cornice, metal hipped roof, generous public spaces and artwork, and allusions to designs of fin-de-siècle buildings in Pioneer Square that it replaced offered a symbolic humanistic rebuke to the scores of flat-topped, sleek, impersonal modernist corporate boxes that were beginning to populate the Seattle urban landscape during this time. The building’s final design, to some degree, represents the will of the people and public debate as much as it did the whim of the designers. As a major public building in the city, it is perhaps not surprising that the building did not escape controversy.

During 1965, the city of Seattle and the General Services Administration (GSA) first clashed over the building’s location. Mayor James d’Orma Braman and the Seattle City Council hoped to place the new federal office building on city and county-owned land between Third and Fifth avenues and Columbia and Jefferson streets as part of a proposed Civic Center to include the King County Courthouse, Public Safety Building, and City Hall. The GSA, however, wanted the steel-frame high rise—projected originally to have approximately 40 stories—on a hilly site bounded by First and Second avenues and Marion and Madison streets on the southwest edge of downtown and the northern edge of Seattle’s historic and commercial Pioneer Square. Braman did not want to use what he deemed to be prime commercial space for a federal building, as the city would lose potential tax revenue. Additionally, the city was also trying to redesign its waterfront and surrounding area, and did not want this plot taken for purposes out of its control.

Three planning studies in the mid-1960s—done by the Bassetti and Graham firms and the GSA itself—suggested that the new skyscraper would have been too tall for the proposed Civic Center; one of these studies stated that the existing Civic Center buildings and the tower would look like “three tomato cans alongside a giant tombstone.” The GSA’s preferred downtown/Pioneer Square site prevailed with the backing of Warren Magnuson (then chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee Sub-Committee), who threatened that Seattle would lose federal funding for the building if the political wrangling continued.

When plans were announced in mid-1965, the design team of Fred Bassetti and Company and John Graham and Company had already been selected. Bassetti had separated from his longtime partner, John M. Morse, in 1962, and was becoming very active in city politics and cultural events. He also became a leader within the Seattle Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), advocating professional engagement in local urban planning issues. A charismatic and gregarious man, he had many connections in the city government and was developing a reputation as an imaginative designer of institutional buildings, mostly in education. Bassetti secured the primary responsibility as the building’s principal designer. The Graham firm had recently designed a new federal office building in Juneau, Alaska, and provided the necessary architectural and engineering expertise in high-rise design—experience Bassetti lacked.

Other members of the building team included Richard Haag Associates, which provided the dynamic landscaping around the building, and Hoffman Construction of Portland, the general contractors. Hoffman offered the second lowest bid for the job and was selected when the first construction company proved “unresponsive” to the GSA. The selection of Hoffman triggered demonstrations from local African American civil rights groups, who charged that the firm had a terrible track record of hiring minority workers.

Bassetti saw this building as very important for his career, and indicated later that he received other important commissions, including that for the American Embassy in Lisbon, Portugal, because of this highly visible project. Given the public nature of the building, he solicited ideas about “what the building should say.” He stated: “The public should have a voice in the design. Not in the actual shape. That is our job. But in what the building says. How shall the building speak to the people?” The people responded by indicating that the building should exhibit strength to express the stability of the federal government, but should be “friendly” to the public who is both funding and using it.

In translating these principles into architectural ideas, Bassetti thought the building should rise above the city, but that its form should not be oppressive. He exercised several design moves to help minimize the building’s 850,000-square-foot bulk, including the chamfering of the skyscraper’s corners and the addition of a band of honeycomb-like panels at the twelfth floor. Bassetti wished the building to have an “honest” character; for Bassetti this meant that many internal uses could be read easily from the outside. A writer for the Architectural Record observed in December 1978: “…the precast concrete skin has been designed for both its substantial proportions and for a liveliness produced by its external expression of the various functions within—such as a customs court on the fifth floor, an auditorium on the fourth, and the varying requirements for mechanical equipment and for natural light as the building rises.” As the building rose, its windows grew larger, acknowledging the internal demand for sunlight and views on the higher office floors.

As for its “friendly” public character, Bassetti limited the building’s height to reduce the foundations and more fully use the land around the base. If the building’s foundations expanded too far, he thought that valuable public space would be lost. Originally, public amenities such as restaurants were located on the first floor and a splendid lobby with brick and teak appointments welcomed visitors. Working with Haag, Bassetti planned a remarkable stairway, inspired by Rome’s Spanish Steps, to climb the 45-foot grade that separated First and Second avenues. This stairway, like all of the plaza, featured a richly detailed brick surface, a hallmark of Bassetti’s work of the 1960s. The steps, shaped like an alluvial fan, contained many levels upon which to break one’s climb and individualized sitting areas and vantage points for public use. Bassetti and Haag also enriched the plaza with several significant works of sculpture, including Isamu Noguchi’s Landscape of Times. A total of 45 works of public art were included in the building and plaza in 1975. An elaborate ensemble of trees in planters further enriched the space surrounding the entryway.

Another controversy about the building’s placement involved the removal of existing buildings from the GSA-preferred site. At this time, public interest in historic preservation was rising in Seattle. Pioneer Square was being resettled by architects, art dealers, and civic leaders such as Victor Steinbrueck, who were reemphasizing Pike Place Market’s adaptive reuse value. A heightened interest in Seattle’s architectural heritage was not enough to save much of the existing fabric around the federal building site, however. Its construction required the demolition of several notable buildings, including the Stevens Hotel, an early “luxury” inn, and the Tivoli Theatre.

Most significant was the January 1971 demolition of the Burke Building, a Richardsonian Romanesque structure owned by former Judge Thomas Burke, an early Washington Supreme Court Justice and Seattle agent for James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railroad. Bassetti wished to preserve the Burke Building, but when this became programmatically impossible, he advocated instead for reincorporating parts of it throughout the skyscraper. To this end, the Burke Building’s front entry arch was repositioned to a prominent spot close to Second Avenue, and other remnants were included in various parts of the plaza and lobby. Finding the artifacts becomes a moment of discovery for pedestrians approaching and entering the building.

Because of periodic disagreements of various kinds, the federal building took 10 years to build and its cost escalated from a 1965 estimate of $25 million to $42.5 million at completion in 1975. Its total cost triggered two further controversies that emerged in 1972. First, the local cultural arts group, Allied Arts, critiqued the 37-story tower, which accommodated 2,500 workers, for providing parking for only 35 cars. Poor sub-surface soil characteristics had made the construction of a 200-car parking garage impossible. This parking shortfall in part prompted Allied Arts to request that an environmental impact statement be written for the new government center, according to provisions of the recent National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), shepherded through Congress by Washington’s own Senator Henry M. Jackson, for whom the building was later named. (It was named for Jackson in 1984 after his sudden death from a heart attack the year before.)

Allied Arts also brought to light another disagreement that was being waged behind the scenes over the cladding choice for the Jackson Federal Building. Because its budget had increased dramatically by 1972, the GSA began to rethink the brick veneer skin that Bassetti had originally specified in part to unify the building with the public plaza. Allied Arts wanted to retain the brick-colored skin and launched a local newspaper campaign to inform Seattleites of the last minute change. Washington, D.C.–based lobbyists for the precast concrete industry pointed out that using their product for the building exterior would significantly cut costs by perhaps as much as a million dollars. The lobbyists even put together a slide show for the Seattle City Council to warm them to the idea of precast panels. Lobbyists who favored brick, meanwhile, fought back to retain the commission for its manufacturers. Faced with a cost overrun, the GSA pressured Bassetti to accept pre-cast panels of honey-beige aggregate highlighted by chips of gray and brown, which he did in November 1973. In discussions with the architect towards the end of his life, he expressed profound regret for the replacement of brick with precast reinforced concrete panels.

Nonetheless, when the first employees of the Government Book Store and Printing Office, Consumer Products Safety Commission, and other governmental units moved into the building beginning in mid-July 1974, they entered one of the most technologically advanced high rises of its time—considered a milestone in the advancement of fire-safety technology. In the 1960s and 1970s, John Graham and Company had developed a reputation for its high-tech expertise. In the Jackson Federal Building, the company experimented with new Honeywell computer-control systems for temperature and fire suppression using ionization-type smoke and heat sensors. Graham designed a central control room, where a single panel could maintain constant room temperatures on each floor and stairwell. Entering through a special door, firefighters could enter the control room and direct fire suppression systems throughout the building. The GSA also used the building as a backdrop for two major fire-prevention conferences held in Seattle in November 1974. GSA Administrator Arthur F. Sampson felt that the Jackson Federal Building set a new standard for fire safety in public buildings, and authorized the preparation of a 25-minute documentary film, The Legacy, featuring the building, to be shown nationally (although whether it was actually produced is unclear).

Despite its construction dragging out over a decade, the controversies surrounding the Jackson Federal Building serve to underscore the strengths of the American political system and the importance of public discussion. While disputes raged over one issue or another, the matters were aired, debated, and resolved—at least to permit construction to proceed. Bassetti had asked Seattle residents what the building should “say,” and they responded. After all was said and done, what they received was a notable statement of what public architecture could be.

References

“Cooperation Pledged as Site Is Picked.” Seattle Times, October 3, 1965.

“Federal Office Bldg. To Be City’s Largest.” Seattle Times, July 29, 1965.

“1st Av. Site Urged for Federal Bldg.” Seattle Times, July 29, 1965.

Lane, Polly. “New Building’s Debut Is Fire-Safety ‘Coming Out’ Party.” Seattle Times, November 17, 1974.

“Seattle Federal Office Building, Seattle Wash.” Architectural Record (December 1978): 118-200.

Welch, Ruth. “The Slingshot that Rocked Seattle.” Seattle Times, October 8, 1972.