You are here

Museum of Pop Culture

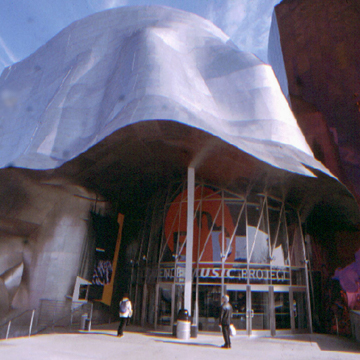

The Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP), formerly called the Experience Music Project (EMP), marks the eastern edge of the Seattle Center with a flamboyant, deconstructivist design possible only with the advent of 3-D modeling architectural software and computer-aided robotic steel fabrication. Completed in 2000, it was the first and only building in Seattle designed by Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry, who had risen to superstardom in the world of architecture at that time. The building sparked considerable debate in the architectural community, mainly regarding the building’s aesthetics and its appropriateness for a center whose architectural legacy was predominantly characterized by futuristic, space-age structures built for the Century 21 Exposition of 1962. As a building for music and pop culture, however, one could argue that its design is entirely appropriate.

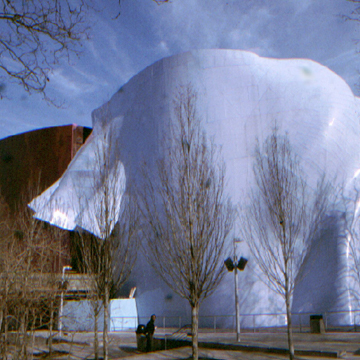

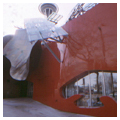

The building’s most striking exterior features are a series of differently colored metallic skins supported by an outer concrete shell that, in turn, is supported on custom-cut steel ribs. The amorphous stainless steel and aluminum skins, variously rose-colored, silver, bronze, red, or sky blue, suggest sea life or other amphibious creatures and are seemingly irrelevant for a museum designed originally to celebrate music. Yet Gehry claimed that the inspiration for the project was a pile of trash he gleaned from an electric guitar shop near his office in Santa Monica, California. To this end, draped over roofs on the east side of the building are a series of metal track-like structures that resemble mangled guitar fretboards at a massive scale.

Much of the structure, which functions acoustically to dampen the sound from competing exhibits, is exposed on the interior. The museum encloses 140,000 total square feet with two entrances on different levels on the northern end, and another entrance on the southern end. The project was funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen.

Prominent interior features include the “Sky Church” (a multi-story space with music and a projection screen) and a two-story guitar sculpture at a central interior avenue that demarcates temporary and permanent exhibits. The basis of the permanent exhibits was established by Allen’s own private collections. These include items once owned by musical artists such as Jimi Hendrix and Nirvana (and others bands from the era of Seattle “grunge”), and, at the lower levels, exhibits on movie genres such as horror, science fiction, and fantasy. There is also a music studio, called the “Sound Lab,” where visitors can experiment with music.

Computer-aided design was integral to the construction of the building, although Gehry’s design process involved roughing out the forms with sketches and more than 100 “maquettes.” Gehry’s office used modeling software called CATIA, developed by Dessault Systems in France, which, at the time, had been used predominantly for design in the aerospace and automotive industries. The electronic 3D model was so integral to the design that paper drawings apparently were skipped, as lasers guided by data from the electronic model cut the elements—an early example of such fabrication for a major work of architecture.

Regardless of the design process, MoPOP is arguably Seattle’s most polarizing building—at least from an architectural perspective. Due to its competing colors and what was perceived as an ill-defined exterior form, upon completion MoPOP was viewed by many critics as far less successful than Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which had been completed just a few years earlier.

Nonetheless, MoPOP occupies a critical place at the Seattle Center, providing visitors with interactive spaces for the appreciation first for music, and later for a range of popular culture attractions.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.