West Virginia's magnificent state capitol, beautifully sited, perfectly proportioned, and handsomely detailed, well deserves its many accolades. One of the country's finest “temples of democracy,” the main building follows the architectural pattern established by the U.S. Capitol, though its dome rises slightly higher. The three-part, U-shaped composition was constructed over a period of eight years. Its 1932 dedication was one of the state's few bright moments during the lean years of the Great Depression.

The fire that destroyed the 1880s capitol on January 3, 1921, made a new building necessary. At Governor John Jacob Cornwell's request, the state legislature appointed a commission to select both an architect and a “suitable location for a complex of buildings of impressive structure.” Although there was talk of an architectural competition, Cass Gilbert, who already had designed capitols for Minnesota and Arkansas, was chosen in July 1921 after visiting Charleston and meeting with the commission. His son, Cass, Jr., who would play an important role as the project moved forward, was with him.

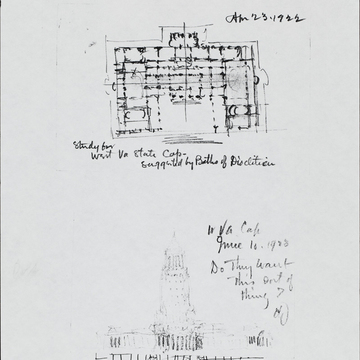

The site, selected in December 1921, was a large tract in the city's residential East End, southeast of downtown and overlooking the Kanawha River. On April 20, 1922, Gilbert confided to his diary: “At office—In late afternoon I struck what I think will be the motif for the West Virginia State Capitol—Cass Jr.… with me.” Except for one brief aberration, the sketch plan that he refined three days later, and the notation “suggested by Baths of Dioclitian [ sic],” remained his guiding design principle throughout the project. On June 30 the commission met with Gilbert in New York and “voted to approve the idea of 3 bldgs. or a main bldg. & 2 wings, and the general style.” Each unit would be let under separate contract, completed, and then accepted by the state before construction began on the next one.

On September 14, 1922, under a banner heading claiming “West Virginia's New Capitol to be Greatest of its Kind—Reckoned Among World's Finest Buildings,” Manufacturers Record announced Gilbert's hopes for the project: “I want to make this Capitol building the crowning work of my life. It is the type of building to which I have devoted the past 25 years and I feel that the opportunity is now presented to me for a splendid architectural monument.”

The first task, site preparation, was far from simple. Of the sixty-five separate properties purchased to assemble the tract, thirty-two contained houses deemed “too good to be destroyed.” In spring 1923 many of them were taken off their foundations and ferried across the river (see CH58). Gilbert refined plans throughout 1923 and, after one particularly grueling session in June—during which one state official suggested a skyscraper capitol—sketched the sole deviation from his original scheme. To the side of his sketch, which showed a building similar to the recently completed Louisiana capitol, he pondered in pen: “Do they want this sort of thing?”

On December 21, 1923, competitive bids were opened for the first unit, the T-shaped west wing. When they proved higher than expected, Gilbert, then in Charleston, “reluctantly decided to abandon the idea of marble for the buildings.” The next day, the commission awarded a contract to New York's George A. Fuller Company, and it was determined that Indiana limestone, not marble, would be used as facing for all three buildings. By this time, former city manager Bonner Hill had been appointed secretary of the commission to oversee construction. Ground was broken for the 300by-60-foot west wing on January 7, 1924, its cornerstone laid on May 1, and the building completed in March 1925 at a cost of $1.2 million. This wing was, and is, primarily an office

The James Baird Company won the bid for the east wing. Construction began in July 1926 and was completed in December 1927 at a cost of almost $1.4 million. The Supreme Court, the building's major space, is a handsome cubical chamber highlighted by screens of Ionic columns in white Vermont marble on three walls. Gilbert's later design for the chambers of the U.S. Supreme Court follows the design of its West Virginia predecessor almost to a fault.

Once the two wings were completed, attention focused on the central building, which would be connected to them by one-story hyphens, forming a U-shaped complex. The Fuller Company received the construction contract in March 1930. Wheeling, Charleston's erstwhile capital competitor, helped build the new structure. The Wheeling Steel Corporation, Wheeling Structural Steel Company, Wheeling Tile Company, and Wheeling Metal Manufacturing Company all provided services and products. Granite came from Milford, Massachusetts, and interior marble from Proctor, Vermont. Travertine floors came from Italy, as did marble for the columns in the Senate chamber. Those in the House are of marble imported from France. The West Virginia Review (August 1931) reported that George P. Reinhard of New York had won the contract for interior design, with the understanding that the firm's Miss Mary Pratt, “formerly of West Virginia,” would supervise the work.

Some critics expressed doubts about the wisdom of building the extravagant, 558-by-120foot central unit in the midst of the Depression. In spite of such concern, construction continued, although the cornerstone ceremony, held on November 5, 1930, was a deliberately low-key affair. Gilbert was even able to convince penny-pinching critics that gilding the dome with gold leaf would be cost-effective. The cost of the main unit was tallied at $4.6 million, including the architect's fees, a sum less than the $5 million originally planned.

The building was dedicated on June 20, 1932, on West Virginia's sixty-ninth birthday. Although prior commitments kept Gilbert from attending the dedication, he provided a description of the Capitol to the editor of the Charleston Daily Mail:

The exterior of the buildings is of Indiana Limestone and is classic in style; in fact, it might more correctly be termed Renaissance. The architectural forms are Roman, with the single exception of the Doric vestibule at the ground floor of the Main Building on the river side. The porticoes and the colonnades of the exterior are distinctly Roman, the two main porticoes being of the Roman Corinthian order.

Gilbert was particularly proud of the steelframe dome:

The Main Building is crowned by a dome of majestic proportion, rising to a considerable height, and is a conspicuous and notable feature of the landscape from every point of view. The gilding on the dome brings out that graceful upward soaring quality, which gives it a large measure of its charm and beauty.

Originally, only the ribs and decorative trophies between them were gilded, and the background was painted a brilliant blue. Before long, atmospheric conditions caused the gold leaf to flake, and gold paint soon replaced the gilding. In 1987 new techniques for adhesion were devised, and the entire dome was regilded between 1988 and 1991.

Inside, the rotunda is reminiscent of the Invalides in Paris, with a balustraded circular well opening from the main floor to the Doric hall below. High above, a 4,000-pound Czechoslovakian crystal chandelier, 8 feet in diameter, hangs on a chain 54 feet below the ceiling of the dome. Metopes in the friezes of the rotunda and Senate and House chambers are embellished with carved decorations symbolic of West Virginia, among them bison heads, shields crossed with tomahawks and peace pipes, and shields crossed with mining picks.

In his dedication description, Gilbert cautioned that “the buildings as they now stand should not be considered as complete.” He advised that sculpture should be placed in the pediments of the two main porticoes, that “mural decorations of an adequate character should embellish the rotunda and the House and Senate,” and that landscaping, including walkways and roadways, should be developed. Some of his suggestions remain to be carried out.

When Gilbert died in 1934, two years after the capitol was dedicated, his son, Cass, Jr., undertook necessary fine-tuning of the building, including analysis of the problems with gold leaf on the dome, and the landscaping. Cass, Jr., later received the commission to design the first of many government buildings that have been erected nearby ( CH35.1).

In August 1929, while the capitol was under construction, American Architect published an article by Cass Gilbert titled “The Greatest Element of Monumental Architecture.” Gilbert noted on his copy of the magazine that he had written the article “one evening in Charleston, West Virginia, in response to Governor Howard Gore for some material he might use in an address or message to the State Legislature.” Accompanied by illustrations of his Minnesota and West Virginia capitols, the text concluded with the sentiment that a well-designed state capitol serves far more than its obvious functions. It is also

an inspiration toward patriotism and good citizenship, it encourages just pride in the state, and is an education to on-coming generations to see these things, imponderable elements of life and character, set before the people for their enjoyment and betterment.… It is a symbol of the civilization, culture and ideals of our country.

His West Virginia state capitol perfectly embodies those noble sentiments.