You are here

University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico is celebrated as a campus whose distinctive regional image is drawn from Pueblo and Spanish Colonial traditions and expressed through a formal reliance on earthen colors, minimal geometries, and strong masses set against a typically bright blue sky. Yet the university’s appearance belies a complex history of planning and building, which reveals less a single, consistent vision than shifting, and even competing, visions for shaping this “pueblo on the mesa.”

The University of New Mexico was established February 28, 1889, by an act of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of New Mexico. Located by that act on a desolate mesa some two miles east of Albuquerque, the university was originally housed at one corner of the site in a single, multi-purpose structure now called Hodgin Hall. The red brick and sandstone building, built in 1890–1892 by the local architect Jesse Wheelock, was in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, a ubiquitous and nearly inevitable convention for institutions at that time. The style was duplicated in a second building, Hadley Hall (1900), only to be abandoned when William George Tight became the university’s third president in 1901.

A young geologist who had just earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, Tight brought with him romantic conceptions of New Mexico’s Native inhabitants, tracing back to the Cliff Dwellers exhibition at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and paralleled by the growing fashion for Pueblo Revival buildings seen in works like Mary Colter’s 1905 Hopi House at Grand Canyon. Working with the local architect (and Columbia College graduate), E. B. Cristy, Tight first commissioned new buildings imitating the pueblos he had visited, and then in 1908 charged Cristy with remodeling Hodgin Hall in the same idiom. Concurrently, and probably with Cristy’s assistance, Tight produced the university’s first—if rudimentary—master plan, laying out the campus with a series of tree-lined avenues focused symmetrically on a projected library and auditorium. Despite Tight’s fascination with the Southwest, the unrealized plan had more to do with Chicago than with the villages of New Mexico.

In 1912, David Ross Boyd, the university’s fifth president and another Midwestern transplant, met with Walter Burley Griffin in Chicago to discuss the development of a more systematic master plan for the campus. In August 1915, Griffin submitted what he called a “nucleus plan” and described as a “compact, continuous pueblo.” Laid out with symmetrical cross-axes, Griffin’s “pueblo” is organized around quadrangles framed by linked building blocks and connecting porticoes. The horizontally stacked forms of those buildings translate the Pueblo Revival into Griffin’s variant of the Prairie Style, combined with Mayan references.

Griffin sent this plan from Canberra, Australia, where he moved in 1913 to oversee the implementation of his plan for the Australian capital. In his absence, Francis Barry Byrne was charged with managing projects in Griffin’s Chicago office, which gave Byrne an opening he was quick to exploit. Although the university issued a joint contract for services to Griffin and Byrne in January 1916, by the following April Byrne was listed as the sole architect for the design of a new Chemistry Building. Byrne simplified Griffin’s elevations to minimal masses set around an interior courtyard. Like Griffin, Byrne deflected the university’s Pueblo Style from revivalism to modernism, although his variant of Griffin’s master plan, dated February 1918, implicitly acknowledged Pueblo and Spanish Colonial precedents by clustering his courtyard buildings tightly together to shape what now read more like plazas than quadrangles.

Except for Byrne’s Chemistry Building and ghostly traces of Griffin’s axes in the placement of later buildings, the Griffin and Byrne master plans were never implemented. After experimenting with a loosely defined “Indian Style” that inflected Southwestern elements with Art Deco detailing—Sara Raynolds Hall (1920) is the best example—the university returned to explicit revivalism when it commissioned Tjalke Charles Gaastra to design four Spanish-Pueblo style buildings, including Carlisle Gymnasium, in 1927; the Dutch-born Gaastra had been a proponent of the style’s mixture of Spanish Colonial and Pueblo motifs since moving from Chicago to Santa Fe in 1918. The Board of Regents approved Gaastra’s designs for conforming “to the design of the older buildings” erected under President Tight.

This “Pueblo” style was enthusiastically endorsed by James Fulton Zimmerman, a graduate of Columbia University and professor of political science who became the university’s seventh president in 1927. Miles Brittelle, recently arrived in Albuquerque from Colorado, refined the style with his design of the President’s House in 1929. But it was left to John Gaw Meem—another transplant, who left New York City for Santa Fe in 1920—to prove convincingly the relevance of pre-modern forms to the complex programs and industrial materials required for modern university buildings. Drawing primarily on the architecture of Pueblo missions, Meem adapted the flexibly hybrid Spanish-Pueblo Style to a wide range of institutional needs. He started in the 1930s with Scholes Hall and Zimmerman Library, two monumental works funded by the Public Works Administration, and continued after the war, producing both modernized works like the Jonson Residence and Gallery and works of strict revivalism like the Alumni Memorial Chapel. The university’s de facto architect since 1934, Meem and his firm designed every building on campus until 1956 and he continued to codify its stylistic image until his retirement in 1959.

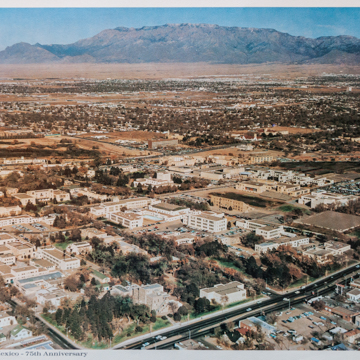

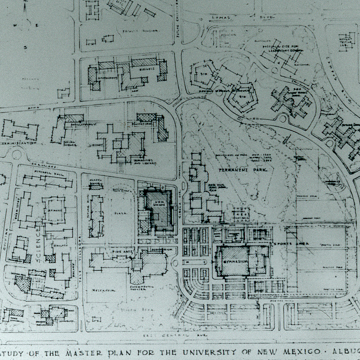

As the campus grew, it merged with the city of Albuquerque, which spread eastward in the 1920s and 1930s to surround the university with residential neighborhoods. Driven by an ad hoc process of growth rather than any plan, the university assumed the form of an urban campus crossed by a grid of streets. Buildings typically stood along these streets or, in the case of important buildings like Scholes Hall, at the terminus of them. Meem and his partner, Edward Holien, tried to rationalize the result in 1954–1955 with a “Preliminary Study for a Master Plan.” Zoned into areas for technology, science, sports, parking, etc., and centered on a “plaza” in place of what was then Zimmerman Athletic Field, this plan at once looked back to Griffin’s quadrangles, and smoothed over the contradictions between a campus whose architecture evoked a pre-modern, rural past, and whose organization increasingly served an industrial, urbanized present.

The plan of Meem and Holien, like the earlier Griffin and Byrne plans, was never executed. But it led to the decision in 1959 to commission the San Francisco firm of John Carl Warnecke to produce the first official master plan since 1915–1918. Rejecting the university’s urban character, the Warnecke General Development Plan called for a completely pedestrian central campus, served by a peripheral loop road, and centered on a landscaped open space with a water feature to the west of Zimmerman Library. Appropriating and confirming ideas going back to Griffin and Byrnes, buildings were clustered around courtyards and patios and grouped into loose quadrangles of related disciplines; accepting the legacy of Meem, new buildings would continue using Spanish-Pueblo forms while staying under the height of Zimmerman Library. In 1962, Garrett Eckbo, a landscape architect based in California, was contracted to implement the Warnecke Plan with the university’s first systematic landscaping plan.

Coming immediately after Meem’s retirement, these plans marked a turning point for the university. The Alumni Memorial Chapel, built in 1960 to Meem’s Spanish Colonial designs, marked the end, rather than a continuation, of the tradition recommended by Warnecke. Over the next three decades, architects who came of age during World War II remade Meem’s campus in a modernist image. This shift from a romanticized New Mexican past to the technological present began under Thomas Lafayette Popejoy, who was the first native New Mexican and University of New Mexico graduate to be named its (ninth) president in 1948. The rupture came in 1961, when the local firm of Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn designed a new College of Education. The industrial structure is directly expressed, and while the battered walls, interior courtyards, and clustered plan echo Southwestern typologies, they do so with the modernist abstraction of Byrne’s Chemistry Building, not the ornamental revivalism of Meem’s Zimmerman Library. Van Dorn Hooker, appointed the first official university architect in 1963, institutionalized this turn to modernism. Though he began his career in Meem’s office, he consistently steered university commissions to like-minded contemporaries until his retirement in 1987.

The Warnecke Plan, as reinterpreted through Eckbo’s landscape plan, would largely be implemented, and despite the amendments of subsequent master plans of 1996 and 2008, its premise of a pedestrian campus remains in effect to this day. Postmodernism came to the campus in the 1990s and early 2000s, producing sheetrock simulations of Meem’s buildings from the 1930s. This has been countered by Antoine Predock’s George Pearl Hall, whose cliff-like facade of cantilevered, cast-in-place concrete has both reasserted the modernist ethic of tectonic expression and found in the region’s landscape a sense of place whose premise is critical rather than revivalist.

References

Hooker, Van Dorn. Only in New Mexico: An Architectural History of the University of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 2000.

Hughes, Dorothy. Pueblo on the Mesa. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1938.

Price, Vincent Barrett. The University of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. 2009.

University of New Mexico. Department of Facility Planning Records. Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

University of New Mexico. Department of Facility Planning Drawings. Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.