The Santa Fe Plaza is the locus of the oldest, continuously occupied capital established by Europeans in the present United States, and is recognized as an important artifact of seventeenth-century Spanish Colonial planning. The plaza’s antiquity is, however, deceptive. Repeatedly rebuilt in response to the imperatives of political power, mercantile commerce, and heritage tourism, the plaza was restored in the twentieth century to a form that suppressed—and often replaced—the material evidence of its complex history with the idealized image of a singular past that never was. Yet traces of the plaza’s multiple historical forms remain and indicate that even the current simulacrum participates in an ongoing narrative of how this public space has persisted and acquired renewed relevance over four centuries of use.

When Spanish colonizers under Juan de Oñate arrived in 1598 to claim New Mexico as a province of New Spain, they occupied the Tewa pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo) near present-day Española. After Oñate resigned as governor in 1607, he was replaced in 1610 by Pedro de Peralta, who was ordered to establish a proper provincial capital according to the “Ordinances of Discovery, New Population and Pacification of the Indians, Given by Phillip II in 1573.” These 148 ordinances addressed the site selection, planning, and political organization of Spanish settlements in the New World, and combined the example of Tenochtitlán (Mexico City) with Renaissance principles informed by Vitruvius and the gridded precedent of Roman colonial camps ( colonias).

The Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís (Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi) was laid out between 1610 and 1612. Obeying the instruction in the ordinances that Spanish settlements be placed away from Indian villages, Peralta chose a site some thirty-five miles southeast of San Gabriel. Located as required on elevated ground near a river, the site had been occupied by Pueblo Indians in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries but was abandoned circa 1450.

The ordinances stipulated that the plaza mayor be at least 1.5 times long as wide, and have two streets at each corner and one from center of each long side. Running east to west between longer north and south sides, the plaza was bordered by the royal houses ( casas reales) or government buildings that included the Palace of the Governors along the western half of its north side; whether or not porticoes ( portales) fronted these buildings, as required in the ordinances, is unknown. A Franciscan missionary church was built in 1610–1612 and rebuilt in 1626–1639 at what was probably the plaza’s southeast corner. In keeping with Spanish Colonial practice, it faced the square despite contradictory provisions in the ordinances that “the plaza… be used for the building of the church and royal houses” but that “the temple of the principal church… shall not be placed on the square.”

The Spanish colonizers retreated from New Mexico during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Led by Popé, a medicine man from Ohkay Owingeh, the rebellious pueblos of northern New Mexico occupied Santa Fe, destroyed its church, and transformed the plaza into a fortified pueblo with three- to four-story housing blocks around two squares with kivas. After the Spanish reconquest of New Mexico under Diego de Vargas in 1692–1693, Santa Fe was gradually rebuilt to the plan preserved in the 1766 map drawn by the military engineer, José de Urrutia.

The oldest surviving record of Santa Fe’s Spanish Colonial planning, the Urrutia map shows that the presumed rectangular plaza laid out in 1610 had been truncated to a square fronting the Palace of the Governors. The freestanding La Castrense, a military chapel finished in 1761 and dedicated to Maria Santissima de la Luz, stood on the plaza’s south side. Single-story adobe residences surrounded the plaza, including along its new east side. Urrutia did not indicate porticoes, though these might have been found on some buildings. Streets at right angles led out from the plaza’s four corners, though the prescribed grid then dissolved into winding rural paths. The destroyed mission church, rebuilt in 1712–1717 as the parish church or parroquia of San Francisco, stood outside the plaza at the head of the royal street ( calle real) of San Francisco that ran up from its south side.

By 1810, Santa Fe had grown into a stable if still-small community of some 3,500 inhabitants. New Mexico remained a geographically and economically marginal province of New Spain, whose development was further restricted by the proscription of trade outside the empire. Mexico lifted this restriction after its independence from Spain in 1821: made a territory of Mexico in 1824, New Mexico was opened to trade with the United States along the Santa Fe Trail that ran from Franklin, Missouri, to Santa Fe. The plaza became a corral for arriving wagon trains, the plaza’s east side filled in with government buildings, and houses of prominent citizens lined San Francisco Street. The adobe architecture increasingly featured porticoes of unfinished wood posts and beams.

The inevitable if unintended consequence of New Mexico’s economic alignment with the United States was its forced political realignment with the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848. New Mexico was officially annexed to the United States in 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and became a U.S. territory in 1850, with Santa Fe serving as the territorial capital. When the U.S. Army under General Stephen Kearney occupied Santa Fe in August 1846, Lieutenant J.F. Gilmer recorded the city in a second map.

Starting in the 1850s, the adobe buildings around the plaza were remodeled or rebuilt with milled lumber porticoes, brick cornices of fired brick, and simplified classical detailing in a regional variant of the Greek Revival called the Territorial Style. The Palace of the Governors remained the seat of government until 1885, and the governor’s residence until 1909, but the plaza’s three other sides were largely converted to commercial use.

In 1852, the merchant James L. Johnson began to develop the plaza’s east side along Washington Avenue (now Old Santa Fe Trail) into a two-story block of adobe buildings with a U.S. Post Office, the First National Bank, newspaper and law offices, and a girls’ finishing school. After the Catholic Church sold La Castrense to Simon Delgado in 1860, the chapel was partially demolished and incorporated into the Delgado Building, a two-story adobe housing a store, warehouse, and residence. In 1863, the plaza was laid out with a symmetrical scheme of radiating paths focused on a bandstand, which was displaced in 1868 by the Soldier’s Monument commemorating the Union Army’s victories in New Mexico in the Civil and Indian Wars.

The arrival of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad in 1879–1880 brought American building materials and styles to New Mexico. As in Las Vegas to the north and Albuquerque to the south, these imports transformed the architecture of Santa Fe. The plaza’s one- and two-story adobes gave way to two- and three-story Italianate commercial blocks, typically of brick, with ground floors opened up by cast-iron columns and plate-glass windows, and pressed metal window hoods and cornices.

Between 1878 and 1883, Italianate buildings were erected to either side of the Delgado Building on San Francisco Street by the Ilfelds and the Spiegelbergs, two prominent German-Jewish mercantile families. The lawyer, politician, and financier Thomas B. Catron replaced the northern half of the Johnson Block on Washington Avenue with the Italianate Catron Building in 1889–1891. The plaza’s Americanization concluded with Rapp, Rapp and Hendrickson’s Greek Revival First National Bank, constructed next to the Catron Building in 1910–1912. The Spanish Colonial porticoes ringing the plaza had mostly disappeared, leaving only the Palace of the Governors and a few Territorial examples like the Delgado Building to document the plaza’s earlier form.

The railroad changed Santa Fe, and threatened its economy. After land speculators demanded exorbitant prices for a right-of-way through the narrow pass between Pecos and Santa Fe, the railroad had bypassed the capital and instead selected Albuquerque as its principal depot and rail yard in New Mexico; an 18-mile spur run from Lamy connected Santa Fe to the main line. Isolated from the mercantile and industrial resources driving the development of Las Vegas and Albuquerque, Santa Fe declined economically and lost ten percent of its population in every decade from 1880 to 1910.

Searching for alternatives, Santa Fe turned to tourism. What Lilian Whiting called the Land of Enchantment in her 1906 travelogue was now marketed as a tourist destination by the railroad and the Fred Harvey Company. At the same time, New Mexico was identifying itself as a tri-cultural union of Pueblo, Spanish (Hispanic), and American (Anglos) peoples in its campaign for statehood. What this identity looked like, however, migrated uncertainly between California Mission, Pueblo, and even Moorish revivals until a group of archaeologists, artists, and architects associated with the Museum of New Mexico invented the Santa Fe or Spanish-Pueblo Style.

Established in 1909 under the direction of Edgar Lee Hewett, the Museum was initially housed in the Palace of the Governors. Museum staff restored the palace between 1909 and 1913, and in 1912 used it to mount the “Old-New Santa Fe Exhibit.” Featuring a model of the portico to be added to the Palace of the Governors in 1913, the exhibit promoted Santa Fe’s Spanish Colonial traditions and argued for their revival. That same year, the municipal Planning Board adopted the “Santa Fe Style” for its comprehensive plan for the city. Rapp, Rapp and Hendrickson’s Museum of Art, erected in 1915–1917 alongside the Palace of the Governors at the plaza’s northwest corner, expanded this style to include elements of Pueblo architecture, drawn primarily from Pueblo missions. The Rapp firm further codified the resulting Spanish-Pueblo hybrid in their design of La Fonda, the tourist hotel built in 1919–1922 at the plaza’s diagonally opposite southeast corner.

The restored Palace of the Governors focused attention on the discrepancy between the plaza’s Spanish Colonial origins and the Americanized buildings erected since 1880. Despite the 1912 exhibit and plan, however, stylistic reform came slowly. A Spanish-Pueblo bandstand replaced the one from 1863 when the plaza was laid out with new concrete paths, cast-iron three-globe lamps, and benches in 1914. In 1929–1930, the industrialist Cyrus McCormick sponsored a competition to redesign the plaza’s commercial buildings with facades that conformed architecturally to the Palace, the Museum, and La Fonda. John Gaw Meem won the competition with a Territorial Revival design that broadened the formal range of the Santa Fe Style, but the project then stalled.

Through the 1950s, the plaza remained as much the city’s commercial center as a destination for tourists. Change happened incrementally, driven by circumstance rather than any stylistic mandate. The Elsberg and Amsberg Building, a Territorial adobe at the corner of Lincoln Avenue on the plaza’s west side, was replaced by the Cassell Building in 1919-1921. Designed by T. Charles Gaastra in the Spanish-Pueblo Style, this mixed-use structure of brick, steel, and concrete housed El Oñate Theater and a Nash and Jordon automobile dealership. The Italianate Kahn Building, erected in 1889 on San Francisco Street next to the Spiegelberg Buildings, was remodeled circa 1930 in a schematic quotation of Spanish Colonial architecture. Its cast-iron columns were disguised as wooden posts, the red-brick facade hidden behind adobe-colored stucco, and the original cornice replaced by a row of fake vigas.

Between 1939 and 1949, Meem combined the three Ilfeld Buildings into a Woolworth’s Five and Dime, remodeling their Italianate facades in the Spanish-Pueblo Style with a recessed wooden portico. The adjacent Delgado Building was replaced by a J.C. Penney’s, built in stages with a steel structure between 1949 and 1955. The department store’s Spanish Colonial facade with its central bell cote evokes La Castrense, whose surviving rear walls were demolished in 1955. Meem applied a Territorial facade to one Spiegelberg Building in 1952, and a Spanish Colonial facade to the other around 1960. In 1953–1954, he remodeled the Cassell Building for the First National Bank, and then converted its earlier building on Washington Avenue into a retail store called Levine’s. Stripping away the Ionic columns, Meem masked Rapp and Rapp’s facade behind an abstracted Spanish Colonial billboard with an overscaled cornice.

The adoption of the Santa Fe Historic Zoning Ordinance in 1957 regulated this ad hoc approach. Drafted by a committee chaired by Meem himself, the ordinance was prompted by the construction of several modernist buildings in Santa Fe’s central historic district: the Centerline Building by John Conron and David Lent (1954, demolished 1985) in particular had alarmed traditionalists. Renamed the Historical District Ordinance and now known as the Historic Styles Act, this design review ordinance prescribed the Santa Fe Style for all new buildings in the city’s center. It did not require the preservation of historic buildings: modern structures could replace authentically historical ones, so long as they reproduced the homogeneous image of a fictionalized past.

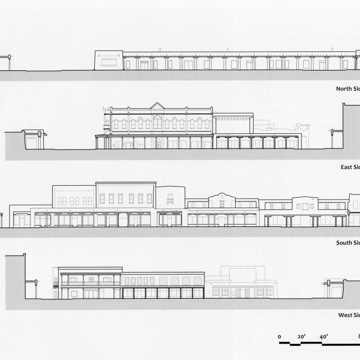

With this instrument in hand, it was possible to complete the stylistic reinvention of the Santa Fe Plaza proposed in 1912. Working with the architect Kenneth Clark, Meem resurrected his 1929 competition project and in 1966–1970 wrapped the plaza’s east, south, and north sides with either Spanish-Pueblo or Territorial Revival porticoes.

The Santa Fe Plaza was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and was included in the historic district in 1973. By that time, nearly everything visible dated after 1909. The Italianate Catron Building, behind its camouflage of tan paint and the Meem portico, was the only structure that belied the plaza’s apparently uniform Spanish-Pueblo and Territorial image.

Rather than diminish the plaza’s value, however, this makeover increased its attractiveness as Santa Fe’s economy shifted more and more to tourism in the last decades of the twentieth century. The department and retail stores left the plaza, succeeded by galleries, luxury boutiques, and restaurants catering to tourists. As Chris Wilson observes in The Myth of Santa Fe, “with its seventy-year history of heritage tourism, Santa Fe offered an already commodified regional culture adaptable as a style of interior decoration, a proven tourist destination, and a magnet… for amenity migrants.” By the 1980s, over a million tourists were visiting every year. They came, and still come, not for Santa Fe’s messy incoherence as an actual place, but for the virtual coherence of its historical simulation.

References

Adams, Eleanor and Fray Angelico Chavez. The Missions of New Mexico, 1776: A Description by Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez with Other Contemporary Documents. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1956.

Bunting, Bainbridge. John Gaw Meem: Southwestern Architect. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983.

Chavez, Thomas E. New Mexico Past and Future. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Crouch, Dora P., Daniel J. Garr, and Axel I. Mindigo. Spanish City Planning in North America. Cambridge: MIT, 1982.

Harris, Richard. National Trust Guide: Santa Fe. America’s Guide for Architecture and History Travelers. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997.

Historic Santa Fe Foundation. Old Santa Fe Today. 3rd ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Kessel, John L. The Missions of New Mexico Since 1776. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1980.

Sheppard, Carl. Creator of the Santa Fe Style: Isaac Hamilton Rapp, Architect. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988.

Simmons, Marc. New Mexico: An Interpretative History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988.

Snow, David H., Cordelia Snow, and Boyd C. Pratt. Santa Fe Historic Plaza Study IV. Santa Fe, NM: City of Santa Fe Planning Division, 1992.

Sze, Corrine P., Beverly Spears, Boyd Pratt, and Linda Tigges. Santa Fe Historic Neighborhood Study. Santa Fe, NM: City of Santa Fe, 1988.

Treib, Marc. Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Wilson, Chris. The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.

Wilson, Chris, and Stefanos Polyzoides, eds. The Plazas of New Mexico. San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 2011.