In a state where forestry is a major source of pride and economic vitality, the Dennis-Selig House is Idaho’s best example of high craft wood construction. The award-winning house masterfully combines high-tech solar engineering with traditional wood craftsmanship. In 1982, Californians Peggy and Reid Dennis asked Seattle architect Arne Bystrom to design an attractive and inviting solar house, where “one would want to go inside, and when inside one would be happy to be there.” His design balances an engineer’s drive towards optimization with humanized attributes that display a cultural sense of place.

The house’s form and function subtly absorb and express many of Sun Valley’s cultural ideals and physical attributes. When it was established in 1936 as America’s first destination ski resort, Sun Valley made explicit associations in its marketing and architecture with St. Moritz in Switzerland, Europe’s foremost mountain health spa/ski resort. The Dennis-Selig House, by contrast, expresses the spirit of the Sun Valley’s associations with San Moritz in more subtle ways.

The house’s broad, east-west enveloping roof recalls the protective and encompassing quality of roofs found in Swiss Alpine chalets. This is the form architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood used throughout his 1937 design for the Sun Valley Village. Like the cantilevered chalet roof, the Dennis-Selig roof extends well beyond the exterior wall and like half-hipped chalet roofs, it flattens in the middle. It differs, however, in that the horizontal portion slopes towards the back of the house, rather than the front. Unlike the chalet typology, it is intentionally asymmetrical in order to, as Bystrom put it, “echo and evoke the surrounding hills.”

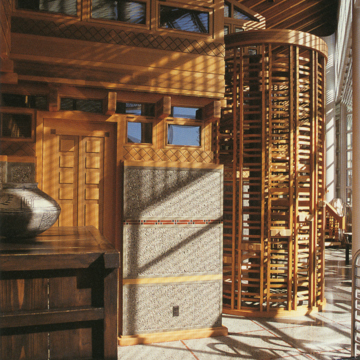

Despite these differences, the house’s design and tectonics display those subtle aspects of Swiss Alpine cottages that John Ruskin described in The Poetry of Architecture. In addition to the shape of the roof, the house’s support structure, joinery, and ornamental woodwork strongly resonate with Ruskin’s depiction of the Swiss attitude towards “neatly” crafted woodwork. Starting from the top, the enormous roof is supported by carefully crafted laminated fir purlins, beams, and tree-like columns that combine together neatly in the articulated joinery. Resemblance to Ruskin’s Swiss cottage continues with walls made of horizontal fir board-and-batten paneling consisting of alternating one-foot boards and two-inch battens. Every third board is ornamented with diamond incisions. As Grant Hildebrand has observed, Bystrom morphs the house’s structural language with details found in China, Japan, Norway, and the work of Green and Green.

As a passive and active solar energy house, the building captures the abundantly crisp high desert sun of Sun Valley boldly on the southwest elevation and highlights its presence with contrasting white window trim and floating white solar collector panels. Inside, the south-facing, two-story “Solar Gallery” consists of public living spaces overlooked by mezzanine level bedrooms—all with dramatic views of Bald Mountain, Sun Valley’s raison d’être. The south-facing, double-paned, argon-filled, heat-mirrored windows boldly frame two-story views of a grove of aspens and the mountain’s ski runs.

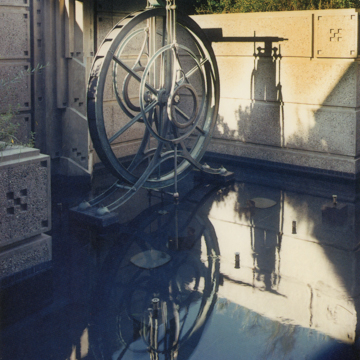

The house’s passive solar energy features complement the building’s overall aesthetic in many subtle ways. Its southwest orientation harvests the warmth and brilliance of Sun Valley’s afternoon sun both inside and out. The outside patio’s orientation to the afternoon sun creates greater comfort in colder temperatures. Many ski resorts like Sun Valley expose their outside spaces to the southwest sun’s radiant heat to ensure their patrons will occupy these areas. A dramatic example of this is found in the hot pools of the Sun Valley resort, where comfortable sunbathing can take place even when temperatures are in the thirties.

Inside the house’s solar gallery, the sun is brilliantly displayed on the horizontal wood panels and concrete work. Its radiant warmth is captured in the exposed aggregate concrete “mass” walls and floor that recall the stonework of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa. The concrete’s mass releases solar heat when the sun dips below the western hills, ensuring a more comfortable even heat in the rapidly chilling late afternoon and evening. The house is passively buffered from the cold north storms by earth berms that merge with the backside of the encompassing double “cold roof.” Like the snug bedrooms of a Swiss chalet, the house’s cave-like bedrooms nestle under the low, sloping roof.

The high-tech solar heating system consists of white solar panels that complement the more traditional wood assemblage. Suspended from the broad roof, the white solar panels float like clouds against a backdrop of exquisitely crafted laminated beams, purlins, and tree-like posts. The panel’s evacuated tubes heat up oil transfer fluid that makes its way down to a rock bed under the main living spaces releasing the sun’s heat throughout its journey.

The Dennis-Selig House expresses the luminous spirit of Sun Valley. While still under construction, the house was awarded the 1985 Progressive Architecture Citation Award. Upon its completion 1987, it received the AIA National Honor Award. Its tectonic qualities are impressive, as historian Kenneth Frampton noted when the house first received national attention, “in the States today, an architecture that is predicated on poetic construction is very hard to find.”

References

Bystrom, Arne. Typed notes on the Dennis house, Bystrom office files. (Undated) Quoted in Hildebrand, Grant, and William T. Booth. A Thriving Modernism, The Houses of Wendell Lovett and Arne Bystrom. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Sun Valley House.” Jurors’ Comments. Progressive Architecture (January 1985): 84-85, 128-130.

Hildebrand, Grant, and William T. Booth. A Thriving Modernism, The Houses of Wendell Lovett and Arne Bystrom. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.

Holland, Wendolyn. Sun Valley: An Extraordinary History. Ketchum: Idaho Press, 1998.

Mead, Phillip. “Salutogenic environments: The use of culture, light and water for the promotion of health.” World Health Design (April 2012): 60-65.

Murphy, Jim. “A Marriage of Disciplines.” Progressive Architecture (April 1987): 85-95.

Ruskin, John. The Poetry of Architecture. New York: J. Wiley and Sons, 1886.