You are here

Slave Pen

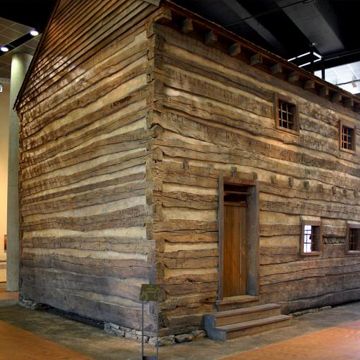

The slave pen housed inside the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, was originally from a farm in Germantown, Mason County, Kentucky. The only known surviving rural slave pen, it differs markedly from the urban slave pens or jails that existed nearby in downtown Maysville, further downriver in Louisville, Kentucky, and as far afield as Alexandria, Virginia. The Germantown slave pen was discovered in 1999 and moved shortly thereafter to Cincinnati.

A native of Virginia, Captain John W. Anderson purchased a hundred-acre plot in Germantown, near the Bracken County line in 1825, and built a home for his wife and their daughters. Although he was listed on tax roles as a farmer, Anderson was a notorious runaway slave catcher who also sold enslaved people for his Kentucky neighbors. By 1830, Anderson was making three to four trips a year to Natchez, Mississippi, for the express purpose of selling enslaved people. Anderson walked his captives the eight miles down the Walton Pike to Dover, Kentucky, where flat boats carried them to Natchez to be auctioned off.

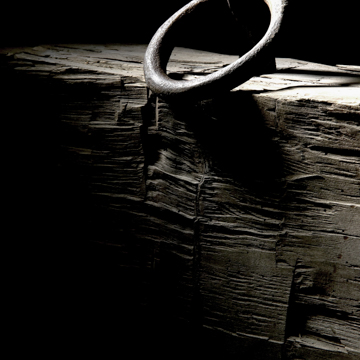

The slave pen is a 26-foot-high, two-story, saddle-notched log cabin measuring 21 by 30 feet. The spaces between the hewn logs were presumably filled with chinking but this had fallen away by the time the structure was identified in 1999. The eight small, irregularly placed windows were barred in 1832. The building was heated and the inhabitants presumably cooked at a 10-foot-wide fireplace with exterior chimney that stood at the short end of the building. In the museum, the location and form of the chimney are suggested by a tubular metal framework, through which visitors now access the interior space. Because the original arrangement of the interior is uncertain, the museum has declined to recreate interior dividing walls and has left the entire second floor open and visible from below. The second floor was presumably accessed by a stair or ladder and may have been subdivided into cells. Evidence of wooden pegs in the walls of the second floor indicates interior partitions of a durable nature. The central floor joist of the second floor is studded with iron rings, to which enslaved people were chained, perhaps two-by-two, with shorter shackles.

Anderson died at the age of forty-one in 1834. Legend has it that he had a riding accident while chasing a runaway slave. After his death, his daughters sold the property to slave trader James McMillen. Eventually, the smaller log structure was housed inside a larger tobacco barn, a common regional practice. While the exact nature of the barn’s history was lost over time, locals never lost their appreciation of its significance. In 1998 Raymond Evers, the owner of the property, inspected the log structure with the intent of tearing it down but after finding the iron rings and recalling local stories, contacted officials at the Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Though Kentucky preservationists protested its removal, the slave pen was sold in trade in 1999 and reassembled at the Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, where it is open to the general public.

References

Brown, Patricia Leigh. “In a Barn, a Piece of Slavery’s Hidden Past.” New York Times, May 6, 2003.

Vlach, John Michael. Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.