You are here

Glover Mansion

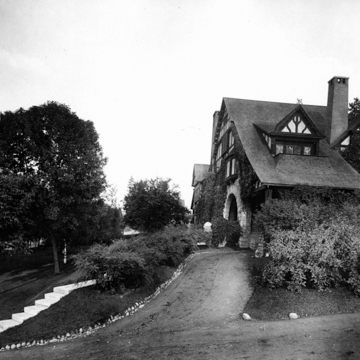

Sprawling across a rocky promontory on Spokane’s lower South Hill, the massive, exquisitely detailed, Tudor-style James N. Glover House helped launch the prolific career of its designer, Kirtland Cutter. Completed in 1888 for early settler and banker James Glover—the so-called “Father of Spokane”—the house’s exorbitant cost, size, and location symbolized the wealth and power of its owner. Its overall design, meanwhile, demonstrated Cutter’s ability to meet client tastes while ensuring that it retained some measure of local character. The Glover House was a central commission for the 23-year old Cutter, after which he was hired to design hundreds of buildings throughout the Pacific Northwest. He later became one of the region’s most celebrated fin-de-siècle architects.

Cutter traveled through Europe before arriving in Spokane in his early twenties, and may have been influenced by the buildings he encountered there, particularly those in rural areas. Along with knowledge of contemporary East Coast–based architects whose work would have been available to him through architectural publications, he brought his talents in sketching (which likely were cultivated as a student at the New York Art Students’ League) as well the climatic and picturesque advantages of the city’s South Hill to the attention of Spokane’s elites. The grand, asymmetrical, and eclectic residences Cutter would design for the wealthy on South Hill were sometimes criticized for looking “old” before they were completed. Yet this characteristic was often desired by those clients who wished to see themselves as heirs of a grand, typically European, tradition. Glover, who amassed an initial fortune through real estate and banking, and who would later become mayor of Spokane, was among those.

Cutter’s work, however, usually bore characteristics of the region in which he worked, although such features were not always obvious. To the untrained eye, the facade of the three-story Glover House, with stuccoed upper stories and its many half-timbered gables and shingled roof in a Tudor style, may suggest a transplant from medieval England. Yet it incorporates rusticated local granite from quarries found by the Little Spokane River, and its asymmetrical massing, with its differently sized gables rising from the granite foundation, seems almost to emerge from the natural landscape itself. A substantial, rusticated granite arch frames the entry beside a porte-cochere that also marks the end of a roof overhang, helping visually to ground the building in its local conditions. Leaded stained glass windows provide glimpses into the interior of the sumptuous, darkly appointed mansion, which features eight different types of wood. These include local fir along with exquisite examples from elsewhere, such as Spanish cherry and Minnesota oak.

The impressively scaled entry arch leads into one of Spokane’s largest residential interiors: more than 12,000 total square feet with eight bedrooms and five bathrooms. Visitors encounter a spacious hall with a grand staircase rising two stories to a 25-foot-high painted ceiling. The hall features three inset wooden arches, one of which includes distinctive built-in seating. An immense fireplace dominates the hall, although perhaps more as a status symbol than anything else, for a wood- and coal-fired boiler in the basement spread radiant heat throughout the house in the winter months, making the house’s four chimneys less crucial to day-to-day operations. An innovative system of cold water piping was constructed to assist in cooling the house in the summer. Wall fabrics in the dining room and the mezzanine are original to the house and the first residential elevator in Spokane—although not original to the design—was installed in 1908 and still operates today. Overall, Cutter’s work provided a dignified setting for dwelling, and entertaining, in late-nineteenth-century Spokane.

Cutter’s architectural oeuvre is difficult to identify with a particular idiom, yet as his career progressed his work more often celebrated wood and handcrafted materials that were characteristic of the Pacific Northwest region, and was perhaps better identified with the Arts and Crafts than any other tradition. The Glover House—though broadly Tudor Revival with its exposed wood and rusticated stone—suggests the Arts and Crafts as well, and could be seen as an example of Cutter’s preferred manner of working.

The house, which the Glovers occupied for only five years (Glover lost much of his fortune in the Panic of 1893), has been privately owned for much of its nearly 130-year history, serving at one point as a Unitarian church. Today it has been renamed the Glover Mansion and is available for catering, special events, and weddings.

References

Bowe, Nicola Gordon. Art and the National Dream: The Search for Vernacular Expression in Turn-of-the-Century Design. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1993.

Matthews, Henry. Kirtland Cutter: Architect in the Land of Promise. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Matthews, Henry. “Kirtland Cutter: Spokane’s Architect.” In Spokane & The Inland Empire: An Interior Pacific Northwest Anthology, edited by David H. Stratton, 142-177. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1991.

McAlester, Virginia, and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to America’s Neighborhoods and Museum Houses: The Western States. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

Nolan, Edward W. A Guide to the Cutter Collection. Spokane: Eastern Washington State Historical Society, 1984.

Poteshman, Nelia, and Nonie Moreau, “Glover Mansion,” Spokane County, Washington. Spokane Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1993. City/County Historic Landmarks Commission, Spokane, Washington.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.