You are here

Old National Bank Building

Daniel H. Burnham left a legacy both on the American landscape and in the American consciousness. Many of his accomplishments can be traced to his influence on American urban planning, from the planning of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago to the City Beautiful Movement, but he also played an important role in the development and articulation of the skyscraper. Most of his firm’s completed designs for skyscrapers were in Chicago or elsewhere in the Midwest or East Coast, but he also completed the 217-foot, 15-story Old National Bank Building in downtown Spokane—the last office building his firm designed before his death. Upon completion, it towered over the surrounding buildings in the city; its scale and classically informed detailing helping to establish Spokane’s reputation as a civilized place in the heart of the Inland Northwest.

Begun in 1910 and completed in just eight short months in early 1911, the Old National Bank Building benefited from Burnham’s years of experience in urban planning and skyscraper construction in Chicago. Similar to some of the buildings completed by his firm in Chicago, such as the Reliance Building and the Railway Exchange Building, Burnham clad the steel-framed Spokane structure in gleaming white terra-cotta and essentially divided the facade into three parts suggesting the base, shaft, and capital of a classical order. This division helped the building offset its otherwise utilitarian nature, and gave to Spokane a classical elegance that the downtown had not featured up to that point—at least not in scale.

The Old National Bank Building is an excellent example of Burnham’s refined, archaic style that made him famous and which may have antagonized less conventional architects such as his Chicago contemporary Louis Sullivan. Unlike Sullivan’s penchant for detailed ironwork, the Old National Bank employed less ornament, emphasizing instead its dignified materials, overall symmetry, and the delicate framing of ample windows. What might at first appear to be two freestanding towers are, in fact, deep projections rising from a three-story base. Together with a thirteen-story connecting tower, they create a U-shaped plan above the two-story base and enclose an outdoor light court. Perhaps anticipating that surrounding buildings would likewise reach to such heights (but harkening, too, to Burnham’s many earlier skyscraper atria), this design, a fairly common massing scheme for the time, allowed daylight to penetrate into the deepest recesses of the building.

Burnham also exaggerated the bank’s vertical thrust by clustering windows into three distinct bays as they rise to meet the classical crown on each of the projections—part entablature, part capital—but never fully denying the presence of the steel frame beneath. What appear to be segmental arches framing large windows on the fourteenth floor provide the building with an eclectic, almost Beaux-Arts, classical flair. The window frames were originally wood, painted a forest green to offset them from the predominantly white exterior.

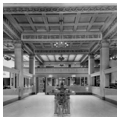

The $1.3 million building exuded luxury and elegance upon completion—ninety percent of which was already leased to tenants prior to opening. Bank customers and office workers entered through a street-level opening marked by Doric pilasters and a four-foot cornice into a spacious, two-story lobby with massive, 23-foot granite Ionic columns. A series of Otis elevators, which helped make such soaring heights possible, stood ready to whisk people to the upper floors. At the very top, an outdoor observatory provided visitors with panoramic views over the city.

The original two-story lobby interior was transformed twice; first in the 1920s with the addition of a mezzanine, and again in 1963 when a floor was installed that divided the lobby into two separate floors. It was during this time that a handful of downtown Spokane buildings along West Main Avenue and North Howard Street, one block from the Old National Bank, were connected via skywalks in conjunction with the multi-level 1967 Parkade garage. In an effort to revitalize downtown Spokane, add convenience to downtown commerce, and cater to the automobile, these developments may have inspired the remodeling of the Old National Bank lobby, which included the stripping of the Ionic columns and the lowering of ceilings. The building continues to serve a bank in its lobby, and leasable office space still extends into the towers above.

References

Korom, Joseph J. The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of Height. Boston: Branden Books, 2008.

Moore, Charles. Daniel H. Burnham, Architect, Planner of Cities. Vol. 1. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1921.

Old National Bank Publicity Department. The Old National Bank Building, Spokane, Washington: The Commercial Bourse of a Prosperous Empire. Spokane: Shaw and Borden Company, 1911.

“Price Paid for Plans: Old National Procured Best Known Architects.” Spokesman Review (Spokane, WA), November 6, 1910.

Schaffer, Kristen, and Paul Rocheleau. Daniel H. Burnham: Visionary Architect and Planner. New York: Rizzoli, 2003.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.