You are here

Tucson Community Center Historic District

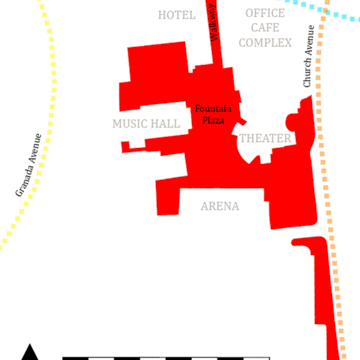

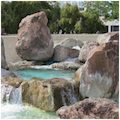

The Tucson Convention Center (TCC) is a performing arts and commercial campus reminiscent of New York City’s Lincoln Center but set within a landscape that bespeaks the city’s high desert surroundings. This Modernist landscape is the work of Garrett Eckbo, one of the most noted landscape designers of the twentieth century. A celebration of water in the desert with a narrative derived from nearby Sabino Canyon, Eckbo’s scheme is composed of three distinct sections. Each one—a small park, a walkway, and a fountain plaza—has an extended water feature composed of geometric forms. The composition is balanced rather than symmetrical, with design elements set off center rather than providing more stable mirror images. Materials include turf-covered earthen mounds, formed concrete, modular brick, natural boulders, and xeric vegetation.

All three sections include linear fountains. In Veinte de Agosto Park, a traditional Moorish/Spanish/Mexican octagonal fountain morphs into a series of abstract geometric basins, which lead, in turn, to the beginning of a designed wash channeled by turf-covered earthen berms. Natural boulders spill downhill along its course.

The narrative of the stream continues in the linking Walkway section, but here the water flow is confined to a narrow acequia or channel, passing under “peephole obelisks” to rise in an “artesian fountain” just before the Walkway intersects with the Fountain Plaza. This section of the design plays with the traditional concept of a symmetrical corridor, but the acequia is placed to one side and edged by a planting of large Arizona sycamores, African sumac, and yellow oleander. On the other side of the acequia is a pedestrian walkway, separated from an office/cafe building complex by a row of smaller potted trees. Here, formal symmetry is replaced by a dynamic suspension of elements set on each side of the off-center water channel. This dynamic balance, typical of Eckbo’s work, is echoed in the Fountain Plaza with an apparently traditional allée set along the edge of Church Avenue. African sumacs line the passageway, but to one side the trees are planted into a sequence of rectangular pavement openings, on the other onto the face of a sinuous grassy berm.

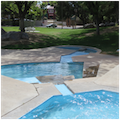

The Fountain Plaza serves as a bajada—an alluvial fan along the base of the mountains. Here the stream flows quickly and noisily, constrained by both geometric concrete forms and by scatters of large boulders that interrupt the water’s path as it rushes towards quiet pools. Berms of earth covered by turf frame the valley above the bajada; natural boulders cascade down the grassy slopes as the level of the plaza rises once again to meet Church Avenue at the eastern edge of the landscape. A classic bubbler fountain of shallow water was designed to entice young visitors near the entrance to the Arena.

In addition to its conceptual narrative, the design is physically linked to the surrounding landscape by extended vistas. Giant pines in the Fountain Plaza and in Veinte de Agosto Park frame views of the Tucson Mountains. A grassy berm in the Fountain Plaza emphasizes the historic Cathedral of Saint Augustine visible above it. Veinte de Agosto Park also serves as a viewing podium for civic buildings and for the Congress Avenue streetscape of restaurants and theaters. Eckbo defined such views as landmarks, noting that people tend to orient themselves in the physical world in relation to landmarks like these rather than to verbal directions, signs, or maps. Such landmarks reference not only downtown Tucson, but also the wider world of the mountains and to Tucson’s Mexican-American heritage—even if the TCC, as an urban renewal scheme, effaced the barrio that was the center of its Mexican-American community. (The wholesale destruction of this barrio energized Tucson preservationists to salvage two historic houses bordering the redevelopment site: the Carrillo House to the west and the Samaniego House to the east. The Arizona Historical Society owns the former and a private developer the latter. Both demonstrate a high level of historic adobe construction practice.)

Across the TCC, the architecture and the landscape display aesthetic harmony. Edward Nelson of Cain Nelson Ware and Bernard Friedman of Friedman and Jobusch designed the Arena, Music Hall, and Leo Rich Theater immediately surrounding the Fountain Plaza. From building to plaza, transitional zones mediate the architecture and landscape, and it is not always easy to distinguish between the two. The Leo Rich Theater features an outdoor balcony reception area planted with bottle trees set off from the plaza with a pony wall. The long arcade of the Arena provides a breezeway with yet another outdoor balcony overlooking the plaza. Planted terraces step down to the plaza level. Large planting boxes and planting terraces on the north and south sides of the Music Hall serve the same function, while the glass facade on the east side of the Music Hall alternately provides a transparent link between the lobby and the plaza, or reflects the plaza back into itself at sunset. The Walkway serves as an indoor/outdoor corridor, sheltered by an overstory of trees, with windows and passageways reaching into the hotel on the west and into offices and cafes on the east. Although Veinte de Agosto Park is not directly adjacent to any building, it is visually linked to the open space of the arcades of the civic buildings located across Congress Street, the stairway to La Placita Plaza, and the adjacent streetscape of shops and restaurants. The boundaries of this space are fluid, integrating indoor and outdoor spaces and reaching out to the surroundings beyond.

Across the TCC landscape, Eckbo’s fascination with the paintings of Joan Miró, Vassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee is evident in his design. Like those well-known modern artists, Eckbo relied on circles as major formal motifs, using them as places of rest and as a source or terminus of lines. Etched into pavement with contrasting brick and concrete, rays emanate from circles and arcs to intersect with grids of trees set throughout the Fountain Plaza. In Veinte de Agosto Park, water collected in an octagonal fountain basin flows through linear channel rays into semicircular or arcing collection basins. The sequence of basins dissolves into a less structured earthen wash, which, in its turn, frames the stairway to La Placita Plaza. In the central Fountain Plaza, angular battered walls interrupt the terraced arcs radiating out from the Music Hall. One form is poised against another, producing a simultaneity of motion and rest.

Eckbo’s material choices enhance the formal composition through deliberate selections based on each material’s unique characteristics. Bricks were employed as modular units, laid in groups to contrast with the plastic character of concrete used for the basins, curving stairways and ramps, and battered walls. Earth berms settled into gently rounded hillocks covered with turf, with defined concrete mowing strips. Natural boulders tumbled down slopes to form random groupings within water features. Deciduous trees like mulberry marked the seasons, while evergreens such as Canary Island pine maintained landscape structure. Defined grass surfaces provided space for informal sitting while reducing heat, glare, dust, and noise. Eckbo’s choice of vegetation had little to do with fashion or ideology; rather, it was based on climatic suitability, color, form, size, and seasonality. He chose plants that would grow well in this specific environment, yet another way he achieved dynamic balance in the landscape.

His plant specifications were also related to how he used light in the landscape, manipulating it in ways that, while commonplace now, were exciting and innovative when introduced in the early 1970s. Among these were his silhouetting of trees and shrubs and his orchestration of light to pass through glass and water. At the same time, Eckbo was attentive to the need for appropriate functional light throughout the landscape. The lighting design for the plaza offered a dramatic evening experience quite different from that of the daytime.

The final element of Eckbo’s design was the living presence of people. Walkways are not only abstract lines, but also paths for walking; grassy berms are not only sculptural elements, but also places for sitting. Whether in motion or at rest, pedestrians complement the flowing water and passive berms to complete the design of dynamic equilibrium. In Landscape for Living (published in 1950), Eckbo emphasized the role of people as actors in his compositions, and this 5.75-acre landscape was intended to be a choreographic green space for Tucson. Today, it remains a leisure landscape for strolling and picnicking, an area for children to enjoy the water and run about while families and friends sit together and chat, and a lunch spot for office workers seeking a midday respite. As a formal entrance foyer for the Arena, Leo Rich Theater, and Music Hall, it serves as an elegant transition to cultural activities and evening performances. As a public plaza, it accommodates major local festivals.

In 1978 the American Society of Landscape Architects recognized Eckbo’s design as an outstanding achievement. In 2015, the TCC landscape was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

References

ASLA. 1978. “Tucson Community Center: Honor Award.” Landscape Architecture (July):300-301.

Birnbaum, Charles A. “Landscape Futures.” Dwell (April 2013): 36-37.

Birnbaum, Charles A., and Stephanie S. Foell. Shaping the American Landscape: New Profiles from the Pioneers of American Landscape Design Project. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009.

Birnbaum, Charles A., Jane Brown Gilette, and Nancy Slade, eds. Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture II: making postwar landscapes visible. New York: Spacemaker Press, 2004.

Bradford McKee, ed. “Three for the Register.” Landscape Architecture Magazine 103, no. 5 (2013):26.

Eckbo, Garrett. Landscape for Living. New York: Architectural Record with Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1950.

Eckbo, Garrett. Urban Landscape Design. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Eckbo, Garrett, Chip Sullivan, Walter Hood, and Laura Lawson. People in a Landscape. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1998.

Gingerich, Sheldon E. “A gem in the art of Urban Renewal: Tucson Community Center.” Arizona Highways 51 (February 1973): 33-35.

Imbert, Dorothée. “Garrett Eckbo.” In Shaping the American Landscape, edited by Charles Birnbaum and Stephanie Foell, 85-87. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009.

Imbert, Dorothée. “Biography of Garrett Eckbo.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Accessed June 15, 2012. http://tclf.org/.

Neckar, Lance M. “Landscape Architecture/Recovery into Prosperity 1950: An international Inquiry into Landscape Design - and the Social, Political, and Artistic Forces that Influenced it - from 1940-1960.” Landscape Journal 16 (September 21, 2007): 211-218.

Otero, Lydia R. La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010.

Pavillard, Dan. “Old Pueblo Has A New Heart: The Tucson Community Center.” Tucson Daily Citizen, October 30, 1971.

Treib, Marc. Modern Landscape Architecture: A Critical Review. Edited by Mark Treib. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993.

Treib, Marc. “Looking Forward to Nature - An appreciation of Garrett Eckbo, 1910-2000.” Landscape Architecture 90, no. 12 (2000):60-67, 88-90.

Treib, Marc. “Church, Eckbo, Halprin, and the Modern Urban Landscape.” Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture II (2004): 56-65.

Treib, Marc, and Dorothée Imbert. Garrett Eckbo: Modern Landscapes for Living. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Walker, Peter, and Melanie Louise Simo. Invisible Gardens: the Search for Modernism in the American Landscape. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

Yetman, Emily. “Eckbo-Designed Tucson Convention Center Landscape.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Accessed May 1, 2012. http://tclf.org/.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.