You are here

1912 Center

The 1912 Center, a former educational facility that currently serves as the city of Moscow’s community center, clearly communicates the ideals of city leaders past and present. The building was originally planned and constructed as Moscow’s second high school during the Progressive Era, a national movement that called for reforms in politics, public education, and other areas of public interest. Educational reform during the Progressive Era sought to expand curriculum and improve design of school facilities. The school’s original design by Spokane architect Clarence Hubbell became the poster child for Progressive Era ideology, and a source of community pride.

Processes for design and construction of the 1912 high school reveal the degree of public interest in architecture during the Progressive Era. Together, the community and architect Hubbell selected a strategically located site on a promontory overlooking downtown. The site’s elevated position afforded an opportunity to heighten the building’s important role in the community and to profile each of its Classical Revival brick and terra-cotta facades. The site was centrally located and readily accessible to each of the city’s established residential neighborhoods. It was located across Third Street from the existing high school.

Progressive Era ideology is manifested in the high school’s design in multiple ways. It was constructed with fire safety in mind, and meant to replace Moscow’s 1891 multistory high school, which was widely considered to be a fire trap. The 1912 school’s structural steel frame was faced with fireproof materials including brick, concrete, and terra-cotta, and the school’s egress system included a central hall, which was bookended by two fully enclosed exit stairs leading directly outside. The 1912 High School was also designed to serve an expanded curriculum, with dedicated spaces for domestic sciences, physical education, and chemistry, physics, botany, and biology labs. The second floor featured an auditorium with a seating capacity of 520. Consideration of student health and well-being was also of utmost concern. Hubbell oriented the school along an east-west axis, allowing for abundant natural light in each classroom. Operable transoms aligning hallways and window walls insured cross ventilation and transmission of daylight to otherwise dark central hallways. Large pyramidal skylights located along the central spine of the auditorium helped to balance light distribution across its full building width.

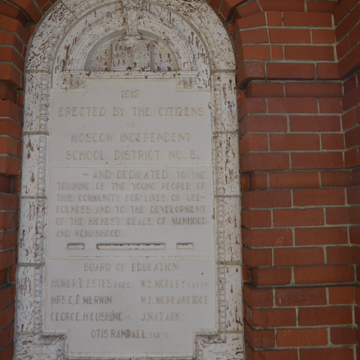

The school’s classical design was intended to inspire students and herald community-wide civic responsibility for education. Identical, non-hierarchical entrances located on three sides indiscriminately welcomed students from all neighborhoods. The act of entry was celebrated through design and detailing: each of the four entrances feature a pair of granite Tuscan columns that support a terra-cotta balustrade and pediment. Terra-cotta entablatures located at the south entrances read: “Erected by the citizens of the Moscow independent school district No. 5 and dedicated to training of young people of this community for lives of usefulness and to the development of the highest ideals of manhood and womanhood.”

The building served as the community’s high school until 1939, at which time the first section of the current Moscow High School was constructed. Between 1939 and 1959, the building was used as a junior high and briefly renamed the Whitworth School. Lower floors were converted for use as school district administrative offices and storage until the building was completely abandoned in 1993. During the intervening years between 1959 and 1993, the 1912 school was poorly maintained, and persisted largely in a state of preservation by neglect. Multiple name and use changes further eroded the building’s identity and perceived value. Considering the building to be a liability, the Moscow School Board contemplated total demolition and conversion of the former school site for use as a playfield and parking lot to serve the current Moscow High School.

Threatened demolition sparked a community-wide debate, inspiring local preservationists to champion a future vision for the building as an important community asset. University of Idaho architecture faculty and students worked together to raise community awareness. They created as-built drawings, design concepts illustrating the former school’s adaptability for multiple uses, public exhibits of their work, and a twenty-minute computer animated video, illustrating the former school’s transformation to a fully upgraded, repurposed structure. Their work, coupled with the efforts of city council member Linda Pall and citizen activists, manifested in the school district’s decision to conduct feasibility studies of the facility’s value to the school district and ultimately to sell their deemed albatross, “The 1912 Building,” to the City of Moscow in 1998. Declaring that not a single tax dollar would be spent towards restoration efforts, Moscow city government contracted with the non-profit organization Heart of the Arts, Inc. to manage the building and lead private fundraising efforts to support the former school’s renewal as a state-of-the-art community center. Following decades of neglect, the former school is in the process of being restored to its former grandeur.

References

Egleston, Elizabeth, “Moscow High School,” Latah County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1992. National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, Washington D.C.

McClure, W., and N. Reese. “Historic Resource or Albatross? Saving Moscow’s 1912 High School Turns into a Community Dilemma.” Paper presented to Pacific Northwest Marion Dean Ross Chapter Society of Architectural Historians, 2006.

McClure, W. The Progressive Era School: Adaptation for 21st Century Education. Film. University of Idaho, 1994.

Otness, L. A Great Good Country: A Guide to Historic Moscow and Latah County, Idaho. Moscow, ID: Local History Paper # 8, Latah County Historical Society, 1983.

Seaman, F. “Report of the Whitworth Review Committee to the Moscow School Board.” Moscow School Board, 1990.

Tonkin, Les, and Atwood, Richard. Whitworth Building: 1912 Moscow High School Feasibility Study. Seattle WA: Tonkin/Hoyne Architects, 1991.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.