Theodate Pope Riddle’s design of Avon Old Farms School in Avon, Connecticut, is a testament to her progressive values in terms of both architecture and education. This boarding school for males is a model of Arts and Crafts values, methods, and aesthetics in the United States. Pope’s progressive program of study, which included hands-on skills and outdoor activities, flourished in the 1930s.

Pope was raised in Cleveland, Ohio, and developed her connection to Connecticut in 1886, when she was sent to Miss Porter’s School in Farmington. After graduation she toured Europe and briefly joined her family in Cleveland before returning to Farmington, where she eventually built her home, Hill-Stead, in 1901. Pope’s training as an architect began when she was tutored by faculty at Princeton University in the 1890s and during the construction of Hill-Stead, when she collaborated and apprenticed with the firm of McKim, Mead and White. Despite her lack of a formal architectural education, Pope became the first female licensed architect in Connecticut and New York. In 1919, she became a member of the American Institute of Architects and in 1926 was appointed a Fellow.

Her desire to create a progressive institution for the education of young men came after her father’s death in 1913. In 1917, she began purchasing land west of the Farmington River, between Avon and Farmington, which eventually totaled almost 3,000 acres. In June 1918, she drew the general plan of the campus and that same year established the Alfred Atmore Pope Foundation, which provided funding and oversight for the project. The first stage of construction began in spring 1921 with the clearing of land. During the fall and winter of 1922 workers laid the foundations for the first buildings.

Pope envisioned the school as a village community in the English style. Inspired by the British Arts and Crafts movement and the utopian and anti-industrialist ideals of William Morris, her design recalled the vernacular architecture of the Cotswolds both in its form and antiquated construction methods. Pope’s plan for the academic and dormitory buildings of the school was organized around two adjoining quadrangles: Pope Quadrangle and Brooks Quadrangle. Each quadrangle consisted of classrooms on the ground floor, dormitory rooms on the upper levels, and distinct master’s cottages at the corners for faculty housing. Attached to the back of Pope Quadrangle was the headmaster’s house and a series of student service buildings and offices known as “The Backs.” Separated from this area by a “Village Green” was a U-shaped group of buildings that included the refectory, bank, chapel, and library.

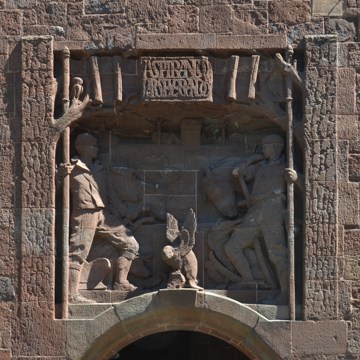

The earliest buildings constructed for Avon Old Farms Schools were utilitarian in nature. The Station House (1921–1923) was built first as a storehouse for supplies and equipment. Constructed by a group of English craftsmen whom Pope hired from the Cotswolds in England, the Station House was located next to the railroad tracks that passed through the western border of the property. Even in this first building, Pope’s vision was clear: an authentic vernacular aesthetic built using traditional methods and hand tools. The Station House was built of stone quarried on the property and featured a gray slate roof. The wooden beams and roof structure were shaped by broad axe and the stone was finished by hand. Pope was so concerned that the buildings appear authentic that she forbade use of plumb lines and levels; everything had to be gauged by eye.

The grouping of utilitarian buildings, known today as the Farm Group, is located at the entrance to the school and includes the Forge (now the Forge Theater), Carpenter Shop (now the School Chapel), Wheelwright Shop, and Water Tower. These buildings, with the exception of the Water Tower (which used more modern construction methods due to its technological requirements), employ fieldstone foundations, red slate and tile roofs, and brick and timber wall construction.

The first group of dedicated school buildings were constructed beginning in 1923, when Pope devoted herself full-time to the Avon Old Farms School project. At the height of construction in 1925, she employed 550 workers. Pelican Dormitory, which forms the north side of Pope Quadrangle, provided the main entrance to the core of the campus and was the first school building erected. The east wall of this structure was built of brick, but it was soon determined that red sandstone quarried on site would be more economical. The choice of this material set the precedent for the rest of the campus buildings. Pelican Dormitory was quickly accompanied by three others, Eagle, Elephant, and Diogenes, which were linked by the master’s cottages located at the corners of the quadrangle. The steeply pitched roofs broken at intervals by dormers are reminiscent of Pope’s previous architectural projects, including Westover School in Middlebury (1909).

In quick succession, houses for the provost and the dean were constructed, along with a kitchen, science buildings, post office, bank, a refectory, and guest house, all located behind Pope’s Quadrangle. In 1928, an estate manager’s house and large garage were added to the Farm Group. With the onset of the Great Depression, construction slowed and eventually ended in 1929–1930, leaving Pope’s original plan of two mirrored quadrangles unfinished. Her original plans for the chapel and library also remained unbuilt. Constructed with non-union labor, Riddle was able to keep the costs down considerably, but conservative estimates for the construction, labor, equipment, and land costs total between $7 and $10 million.

The school opened in 1927 with 48 registered students. The organization and operation of the school, which was governed by a “Charter of the Village of Old Farms” and included a working farm, carpentry and printing shops, and other trade facilities, was intended to build the character of the young men attending. During World War II, the school closed and was used by the U.S. Army as a rehabilitation center for blind veterans until 1947. Pope died at the age of 78 in 1946, before the school returned to its prewar prominence. It reopened in 1948 and continues to operate today. New facilities have been added to the campus in the interceding decades, but Riddle’s designs still form the core of the campus and have served as stylistic inspiration for the new construction.

References

“Avon, Old Farms: A School for Boys at Avon, Conn.” American Architect (November 1925): 391-394.

Brooks, Emeny. Theodate Pope Riddle and the Founding of Avon Old Farms. Avon, CT: Avon Old Farms, 1973.

Callahan, Tara. Theodate Pope Riddle: A Pioneer Woman Architect. Conshohocken, PA: Eastern National, 1998.

Katz, Sandra L. Dearest of Geniuses: A Life of Theodate Pope Riddle. Windsor, CT: Tide-Mark, 2003.

O’Gorman, James F. Hill-Stead: The Country Place of Theodate Pope Riddle. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010.

Paine, Judith, and Roger Baldwin. “Avon Old Farms School: The Architecture of Theodate Pope Riddle.” Perspecta 18 (1982): 42-49.

Paine, Judith. Theodate Pope Riddle, Her Life and Work. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1979.