You are here

Long Walk

The Long Walk, the only structure in the United States designed by the British architect William Burges, is an important example of late-nineteenth-century collegiate architecture and the High Victorian Gothic style in America. In 1872, Trinity College, one of the oldest Episcopal colleges in the United States, sold its original campus adjacent to Bushnell Park to the State of Connecticut for the construction of the new capitol building. Trinity’s president, Abner Jackson, intended to use these funds to build a large suburban campus that he hoped would surpass the great academic institutions here and abroad. To this end, he traveled to England to study the collegiate architecture of Oxford and Cambridge, as well as contemporary works such as George Gilbert Scott’s University of Glasgow. To realize his ambitions for Trinity, Jackson turned to Burges, one of the principal promoters of the Gothic Revival in Victorian Britain.

Burges developed a master plan for Trinity College that followed Jackson’s preferred precedents. Construction of the first part of this new college began in 1875 on a 78-acre site south of the city center in an area called Rocky Ridge. The Long Walk, a continuous structure stretching 900 feet along Summit Street, is composed of a large entryway (Northam Towers) flanked by two wings divided by central pavilions. The south wing (Seabury Hall) features large, pointed-arch trifora windows with sexfoils above. The interior was originally designed with a two-story library and museum on one side and lecture rooms, offices, and laboratories on the other. Additional lecture rooms were also planned for the attic story, but this space was initially used as a chapel. The other wing (Jarvis Hall) housed student and faculty accommodations. It features a three-story exterior articulated with small trefoil-headed lancet windows. The student dormitory rooms, still in use today, consist of two-bedroom suites with a shared sitting room arranged in pairs around six separate staircases with bathrooms in the basement. The central pavilion was originally intended to house junior professors. The buildings of the Long Walk were constructed using primarily brownstone quarried nearby in Portland, Connecticut, and are accented with white Ohio limestone.

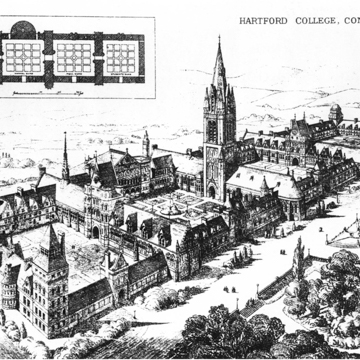

As it stands today, the Long Walk is a small part of the much larger campus that Burges originally envisioned. His master plan was centered on a group of quadrangles. Initially, he proposed an L-shaped arrangement with three quadrangles featuring a central large hall and chapel with a monumental tower. Emulating English colleges built over numerous centuries, Burges employed different Gothic motifs for each group of buildings. Once the Rocky Ridge site was purchased in February 1873, he revised his initial scheme to create a linear, roughly symmetrical set of four quadrangles aligned with Summit Street. As with his first plan, the hall and chapel with large tower remained at the center of the college. The other quadrangles were to be divided by matching gatehouses flanked by wings with the library, museum, art gallery, and a group of common rooms. Around the perimeter were lecture rooms as well as housing for students and faculty.

After the building committee had accepted Burges’s plan, Trinity College sent the young local architect Francis Kimball to London to produce cost estimates and assist in the creation of working drawings, most of which still survive in the college archives. In 1874, Kimball returned to Hartford and produced a wooden model of the plan. But by the next year, due to the projected cost of the new buildings (nearly one million dollars), the four-quad plan was reduced in size and scope. Specifically, the two central quadrangles were combined into one large space. Another key revision reversed the compositional focus of Burges’s original design, which turned inward towards the quadrangles, like an Oxford college, and had no single monumental entrance. The revised scheme featured a large central gateway with turrets that faced outward toward the city and a semicircular terrace.

Although Burges appears to have approved these changes, Kimball executed these designs after returning to Hartford. Kimball also oversaw construction of the Long Walk beginning with Jarvis and Seabury halls in 1875 and continuing with Northam Towers in 1881. While the earlier two buildings closely resemble Burges’s designs, the central entry pavilion, which is flanked by four towers with pyramidal roofs and a cylindrical turret on the west side, was likely Kimball's work, despite containing motifs found in the British architect’s earlier schemes. The interior planning and exterior finishes of the Long Walk buildings, especially Jarvis Hall, were also informed by Russell Sturgis’s recently completed Durfee Hall at Yale University, which similarly features quarry-faced brownstone with white limestone detailing.

Burges also had planned to adorn the college with a complex sculptural program. Believing that sculpture was essential to architecture, he intended for this work to be produced by his favorite sculptor, Thomas Nicholls, and shipped from England. Due to cost constraints, little of this sculpture was executed, and even today some architectural elements remain uncarved.

After the completion of Northam Towers, work on the Burges/Kimball plan largely ceased. In the 1890s, the administration began erecting smaller freestanding structures around the campus. This practice continued until the completion of the Williams Memorial in 1914. Designed by Benjamin Wistar Morris, this stylistically sympathetic structure was the first addition to the north end of the Long Walk. Later, in 1958, it was connected to the Downes Memorial and Clock Tower, which, unlike the earlier structure, was built in a Tudor style using red brick. A large stone neo-Gothic chapel, designed by Philip Frohman based on English collegiate models, was also added to the north side of the main quadrangle in 1933. The south side of the Long Walk was also expanded beginning in 1931 with the addition of Cook Hall and Hamlin Hall. Designed by James Kellum Smith of McKim, Mead and White, these Gothic brownstone structures, along with the adjacent Clement Chemistry Laboratory and Goodwin-Woodward Hall, recall the massing and general articulation of the Burges/Kimball buildings, while simplifying their fenestration and detailing. The buildings of the Long Walk were most recently restored under the direction of the architectural firm of Smith Edwards in 2008.

References

Armstrong, Christopher Drew. “‘Qui Transtulit Sustinet’: William Burges, Francis Kimball, and the Architecture of Hartford's Trinity College.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59, no. 2 (June 2000): 194–215.

Crook, J Mordaunt. William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Knapp, Peter J. “They Should Stand for Ages”: William Burges, Francis Kimball, and Trinity’s Long Walk Buildings. Hartford, CT: Trinity College, 2009.

Weaver, Glenn. The History of Trinity College. Hartford, CT: Trinity College Press, 1967.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.