You are here

Harold Price, Sr. House

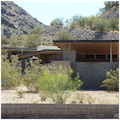

The winter residence of MaryLou Patteson Price (1900–1978) and Harold C. Price, Sr. (1888–1962) is perched on a hillside in Paradise Valley, a wealthy independent enclave at Phoenix’s far eastern end. The Price House was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1954, at the end of a long and illustrious career. It is one of 11 works in the Phoenix metropolitan area realized during the architect’s lifetime and the largest of the seven local residences that Wright designed.

Harold Price first met the famous architect at Taliesin in Wisconsin in 1952, when he commissioned Wright to design his company headquarters in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Price was an entrepreneur and millionaire who had moved to Bartlesville in 1915 to work as a chemist in a zinc smelter before starting an electrical welding shop in 1920. As the region’s petroleum industry grew, so did the H.C. Price Company, general contractors of pipelines. Wright’s 19-story Price Tower was constructed between 1953 and 1956. Contemporaneously, Wright also designed what was lovingly referred to as “Grandma’s house,” a desert vacation residence where the Prices could entertain their two sons and six grandchildren. Unlike the 221-foot-high Price Tower, which is a stark visual marker on the flat prairie landscape, the 170-foot-long, low-slung Price House is subtly nestled into its 9-acre desert site, a clear embodiment of Wright’s belief that buildings, especially houses, should sensitively interact with their surroundings, not be imposed upon them, and that desert structures should mimic the colors and textures of the landscape while promoting simple lines.

The long and narrow house is a series of interconnected volumes (rectangles and squares) that align and flow into one another, almost like train cars in succession: a four-vehicle carport; separate, two-room servants’ quarters; and one larger central volume with ten rooms that radiate like a railroad roundhouse. The pinwheel plan is a variation of a formal typology from early in Wright’s career, in which smaller private spaces configured along parallel axes dynamically emerge from a major node. Here, a 1,000-square-foot atrium divides the public sphere in the southwest (containing the kitchen and dining and living rooms) from the private northeastern wing (which includes five bedrooms and bathrooms). The open-air atrium’s flat, steel-framed roof rests upon thin steel pipes fixed atop the mass’s inverted pyramidal, concrete-block pylons. This creates two-foot-high clerestory apertures that allow fresh air to circulate while giving the roof the appearance of hovering above the core. With the roof’s deep eaves provide shade the flat cap is reminiscent of a ramada, or shade structure, utilized by Native Americans and Spanish colonists who dwelled in desert climes. An open, square oculus is aligned with a central water basin and copper fountain that draws attention to the house’s arid surroundings. As the heart of the complex, the atrium contains Wright’s signature hearth, here circular with a copper-hooded fireplace, in its eastern corner.

The Prices were wealthy and their house is large—at 5,300 square feet it was more than five times the U.S. average in the 1950s—but to some extent the Price House can be understood as an example of Wright’s Usonian House innovation, which he utilized between 1936 and 1959 as a residential type for middle-class clients. Conceived as practical plans for servant-less houses, Usonian houses were single-story edifices with flat roofs and level interiors (usually slab-on-grade). Through them, Wright perfected the open floor plan, in which the kitchen, dining, and main living areas flow into one another. Kitchens, which Wright called “workspaces,” were small yet efficiently designed, while the dining space typically featured a built-in table and buffets. Usonian bedrooms, as in many of his houses, tended to be small and secluded; their lower ceilings and smaller fenestration were meant to encourage family members to utilize the higher-ceilinged, brighter living room, which featured built-in seating as a space-saving measure. Usonian housing also employed new construction techniques, such as sandwich walls (used in the Price House), in which two layers of wooden siding flank a plywood core and building paper, the interstitial spaces allowing for electrical conduit.

The Price House also exhibits five major design tropes of Wright’s oeuvre. The first is materiality: Wright believed materials should be left in their natural state to express their essence honestly. The Price House is composed of standard materials that contrast in texture, color, and feel. The exterior walls are unpainted concrete blocks punctuated by steel casement windows, while the interior is clad in Philippine mahogany, with warm brown tones that contrast sharply with the cold gray of the concrete. The rich turquoise upholstery and shiny copper and brass fittings and light fixtures in the main living areas offer a further contrast with these earth tones. The same turquoise appears in the decorative copper fascia, found throughout the exterior and interior, as well as adorning the steel pipes which support the atrium’s roof.

Horizontality and explicit geometry are also a theme in the Price House, as seen in the atrium’s tapered pylons, in which each layer becomes 3/8 inches wider than the one that preceded it. The blocks’ horizontal joints are raked, which further emphasize the horizontality of the low-slung building. Geometry is expressed in the grid motif of the atrium’s tile floor and repeated in the Tectum ceiling panels made of excelsior, a shaved-wood and concrete composite. It is also expressed in the abstracted geometry of the mural screens in the atrium, designed by Eugene Masselink, a graphic artist and Wright’s assistant, who studied painting at Ohio State University before joining the Taliesin fellowship in 1933. His functional, yet highly artistic screens, which limit wind and sunlight, employ wood and metal painted in primary colors and shaped in geometric forms. The copper fascia, which also lines the dining table’s edge, features a stamped design, almost Aztec in its abstract geometry.

As in so many of Wright’s houses, there is a high level of custom and artistic detail in the building, its fixtures and its furnishings. In the Price House, Wright remained true to the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art.” From built-ins to decoration, each detail throughout the house was carefully designed to create a coherent artistic environment.

Wright’s architecture is also defined by sculptural space. He often juxtaposed rooms with low ceilings and compressed space and rooms with high ceilings and windows that gave the impression of spatial expansion. At the Price House, the story-and-a-half atrium and the naturally lit living areas contrast with the single-story bedroom wing lit solely by fixed clerestory windows and north-facing casements. This spatial contrast is also evident in Wright’s integration of the indoors with the outdoors: not only is the atrium open to the elements, but the living room features operational windows that offer views of the mountains and desert beyond, linking nature and shelter. Glass doors lead from the atrium to the two wings, while a balcony from one bedroom overlooks the atrium. Outdoor space is designed as indoor space: on the northeast end of the house, Wright provided a grassy children’s play yard with a large swimming pool. Playfulness with space is also seen in how the built-ins mark their own territories within a given space. For instance, the high-backed, heavily-massed dining room chairs define space within the boundaries of the eating area, and the four bedrooms extending from the atrium are grouped in pairs to form interconnected suites; and if all the doors are left open, a hallway appears.

Light is another critical element of Wright’s architecture, and he frequently uses it in an almost sculptural way. Here, the roof eaves are wider on the southern exposure than the northern, a reflection of Wright’s attentive response to Arizona’s summer heat. The exterior fascia creates geometric shadows on the concrete walls, while the intricate designs of the steel casements do the same on the interior. Natural light floods the interior through skylights and clerestories, but is kept at bay with Masselink’s screens and mahogany shutters mounted with piano hinges to preclude all light.

Three years after the house was completed, Wright added a master suite to replace the original master bedroom at the far end of the northeast wing, which Price complained was too small and lacked sufficient closet space. The 20 x 40–foot rectangular extension (which expanded into the grandchildren’s play yard) was placed at a perpendicular angle to the original bedroom corridor.

In the late 1960s, the house was sold to U-Haul founder Leonard Samuel Shoen (1916–1999) and his family resided there for nearly three decades. Since 2014, the Price House Foundation has maintained the house, including its original furnishings and Wright’s all-encompassing design aesthetic.

References

Cheek, Lawrence W. Frank Lloyd Wright in Arizona. Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2006.

“The Harold C. Price/U-Haul House: A Video Tour by Frank Henry.” Price House Foundation. Accessed December 12, 2015. http://pricehousefoundation.org/.

“Harold Price, Sr. House.” Frank Lloyd Wright Sites. Accessed December 12, 2015. http://franklloydwrightsites.com/.

Hess, Alan. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Houses. New York: Rizzoli, 2005.

“History.” Price House Foundation. Accessed December 12, 2015. http://pricehousefoundation.org/.

Laseau, Paul, and James Tice. Frank Lloyd Wright: Between Principles and Form. New York City: John Wiley and Sons, 1992.

Legler, Dixie. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Western Work. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999.

McLendon, Sandy, and Joe Kunkel. “Eugene Masselink, Assistant to a Genius.” JetSetModern. Accessed December 12, 2015. http://www.jetsetmodern.com/.

Perkins, Scott W., “The Price Tower,” Washington County, Oklahoma. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 2007. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Ruth, Kent, “Price Tower,” Washington County, Oklahoma. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1974. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Storrer, William Allin, and Frank Lloyd Wright. The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalog. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.