Designed in 1952, the Ball-Paylore House reflects the innovative solar energy design ideas of Arthur Brown, an architect far ahead of his time. The compact suburban house is oriented to capture the ideal southeastern solar exposure with a large outdoor patio covered with a moveable awning system. The house’s passive shading system provides an ideal accommodation to the daily and seasonal climate fluctuations in Tucson.

The house was designed for Phyllis Ball and Patricia Paylore, University of Arizona librarians who wanted a house that would provide a modern contrast to most residential developments of the 1950s. In selecting Arthur Brown as their architect, they chose one of the few modernists practicing in Tucson the first decade after World War II. Brown rejected as “dishonest” the southwestern romantic revival styles popular in Tucson at the time, and he challenged himself to design “without style.”

Before coming to Tucson in 1936, Brown received an architecture degree from Ohio State University, worked as a draftsman for the Chicago firm of David Adler, and during the Depression worked in the Architectural Gadget Design Department of the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition. By 1941, Brown had opened his own architectural practice, and, in 1961, became the first Arizona architect invested in the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). By the time he retired in 1991, he had completed more than 250 projects, and his work had been published in 95 books and journals, including Architectural Forum, Architectural Record, Sunset, and House Beautiful.

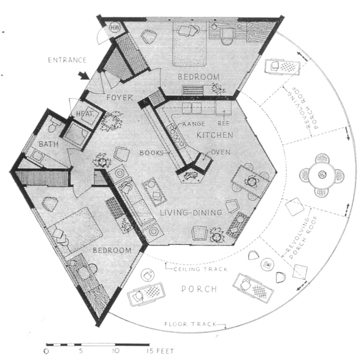

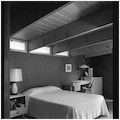

In plan, the 1,203-square-foot Ball-Paylore House is a combination of a partial hexagon of indoor spaces and a partial circle of a southeastern-facing outdoor patio space. The core area of the indoor space, including the library, living room, dining room, and kitchen, is one continuous room anchored by a brick fireplace. The two bedrooms are trapezoidal segments on opposite ends of the core public area, separated by a third segment consisting of the bathroom and street-facing entry. The open, compact floor plan is reinforced by the occupants’ desire for minimal furniture, including in the bedrooms, which each contain a single bed and a built-in desk.

The house is constructed of exposed double-wythe brick with a mortar wash finish on the exterior consistent with Brown’s utilitarian aesthetic. The extremely low-pitched roof plane is supported by exposed wooden beams radiating out from the chimney hub of the house to just beyond the exterior walls. Floor-to-ceiling sliding glass doors line the southeastern-facing facade to provide ideal solar exposure to the bedrooms and living and dining rooms, and blur the definition between indoor and outdoor spaces. The exposed concrete floor slab is colored with a golden-brown pigment and provides substantial thermal mass to absorb and later radiate heat from the low winter sun captured from the southern exposure. The outdoor patio slab fills out the remainder of the plan in a semicircular form with access from each of the public and private rooms.

The most innovative feature of the house is the lightweight revolving porch awning that wheels on circular tracks at the edge of both the roof plane and patio slab. The porch roof system is composed of two moveable corrugated aluminum awnings supported on lightweight tubular steel frame that Brown called “sky shades.” The sky shades can be moved to protect or expose the southern facade depending on the season or time of day. As a visual demonstration of the ease with which the sky shades could be moved, the photographs accompanying the 1962 House Beautiful article on the house show the diminutive Phyllis Ball pushing the awning system along its track.

The only other fenestration in the house is a set of operable ribbon windows in each of the bedrooms and bathroom, inserted between the radially aligned heavy wooden roof beams between the top of the exterior wall and the roof plane. In addition to improving cross ventilation, the windows’ locations under the extended roof plane prevent direct sunlight from the northern and western exposures, the least desirable during the hottest summer months. A two-car open carport extending from the core of the house further protects this northwestern, street-facing facade. In contrast to its neighboring suburban, postwar ranch-style houses, the Ball-Paylore House’s minimally exposed street facade is otherwise obscured from the street by the natural desert landscape.

Describing their house in the 1962 House Beautiful article, owners Ball and Paylore characterize Brown’s scheme as “small, simple, and inexpensive, but is nevertheless imaginative, unusual, and aesthetically satisfying, proving that it is possible to build a house on this scale while avoiding the trite, conventional, and the dull.” Brown, known for his inventive solutions to architectural problems, used his career to experiment with inexpensive materials and modular forms. Ideas such as subterranean houses, subfloor radiant heating, aluminum and foam insulated roof components, revolving patio covers, and self-supporting hyperbolic paraboloid shade structures established his reputation as a modernist with a sensitivity to the desert environment of Tucson. Many of Brown’s innovative buildings, including what was claimed to be the country’s first passive solar-designed school, have since been demolished, leaving his surviving buildings, like the Ball-Paylore House, as unique exemplars of his creative genius. After Paylore’s death in 2003, the house was transferred to longtime university friends. It remains in private hands though it is frequently used as a guesthouse for visiting scholars.

References

Arthur T. Brown: Architect, Artist, Inventor. Tucson: College of Architecture Library, University of Arizona, 1985.

Murray, Carolyn S. “For Two Busy People: A $16,225 House for a Difficult Climate.” House Beautiful(October 1962): 200-208.

Nequette, Anne M., and R. Brooks Jeffery. A Guide to Tucson Architecture. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2002.