The University of Arizona is a 325-acre campus located in mid-town Tucson. The integrated environment of buildings and landscape features has been designed and constructed incrementally since the university’s founding in 1885. This cultural landscape includes thirty-five historic buildings and a park-like environment whose unique diversity of plants from arid regions throughout the world is now a nationally recognized arboretum.

The built environment of the University of Arizona developed in four phases. The campus’s first structures were erected without any comprehensive campus plan on the original 40-acre parcel far outside the incorporated town of Tucson. Built between 1885 and 1918, these structures featured a range of architectural styles. Completed in 1891, Old Main, which is best described as vernacular Queen Anne, continues to maintain its position as the axial center of campus, from which buildings and landscapes extended over subsequent generations. Other buildings in this first phase of campus development included an eclectic mix of Queen Anne and Classical Revival styles that reflected Arizona’s pre-statehood aspirations for national credibility.

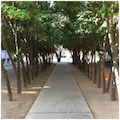

The University of Arizona was also designated as the state’s land grant institution, meaning it received support from lands passed to the new state by the federal government in 1912. An agriculture experiment station was established in 1891, transforming the campus into a living laboratory that focused on plants from arid regions throughout the world. An environment of imported Mediterranean species, including olives, pines, sumac, cypress, and bitter orange, irrigated by water-consumptive flood basins, was part of the late-nineteenth-century vision to transform the Arizona desert into an oasis. Streets and walkways lined with parallel rows of olive and date palm trees, allées of fruit trees, fruit and vegetable gardens, and grass lawns created the shady, tranquil environment that continues to distinguish this campus as a park within the city. In addition, a desert garden of more than 600 species of cacti and succulents was established and used as a research laboratory.

The second phase of campus development is marked by the creation of a campus plan by John B. “Jack” Lyman in 1919. This plan combined a formal academical village composition, based on Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia campus, with the naturalistic secondary roads and paths inspired by Fredrick Law Olmsted’s park designs. In this campus plan, a central lawn or mall defines an axial orientation between the campus main gate to the west and Old Main to the east, with academic buildings on the north and south sides of the lawn. Outside of this formal layout is a secondary row of dormitories on each side of the principal set of academic buildings, placed along curvilinear roads creating a less formal, and almost residential, character.

In this second phase of construction, there was a dramatic shift toward a consistent architectural vocabulary grounded in academic classicism, one that incorporated features of Roman, Renaissance, and Romanesque revival styles. Roy Place, the university’s de facto campus architect from 1914 to 1940, was responsible for creating a uniformity of architectural character in over forty buildings, resulting in a quality of craftsmanship that is still aspired to today. His signature stylistic elements—arched openings in the principal facades, the use of red brick, and the integration of terra-cotta detailing—continue to distinguish the historic core of campus buildings, best seen in the library building (now Arizona State Museum) west of Old Main.

The third phase of campus development occurred in the generation after World War II, when the campus expanded to meet the needs of veterans taking advantage of the GI Bill. Campus growth pivoted from the west side of Old Main to the east side, anchored by a half-mile long, rectangular grass lawn or mall, originally conceived in the 1931 campus plan by Roy Place. The east mall is defined by parallel drives and is lined on the outer edges with academic, research, service, and athletic buildings, whose siting maintained the previous Jeffersonian academical village concept combined with an architecture that embraced the minimal functionalism of modernism.

The fourth, and current, phase of campus development, spanning the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, moves away from the previous uniformity of both architectural style and the increasingly monotonous red brick sheathing. Campus planning, still centered on the linear axis of the east mall, expanded its footprint and developed consolidated functional and disciplinary nodes that form quadrants, each with a distinct character. Comprehensive campus planning efforts continued the use of open space, pathways, and other landscape elements to integrate an increasingly eclectic and boldly individualistic architectural expression during this phase, including the Stevie Eller Dance Theatre, Meinel Optical Sciences Building, and Poetry Center.

In the 1960s, the campus’s landscape palette shifted to desert-adaptive plants, including carob, jacaranda, pepper, and rock fig, from other arid regions throughout the world. In 1999, what once was a botanical proving ground became a federally recognized arboretum with twenty designated heritage trees, nine designated “great” trees (the largest of their species in Arizona), and a comprehensive inventory and educational program with interpretive signage throughout campus.

Campus preservation efforts, including the 1985 National Register Historic District listing for the university’s original west campus and the 2006 preservation master plan, were critical to the long-term planning process by identifying the iconic campus character elements that, in turn, defined the principles for future campus development and preservation.

References

Ball, Phyllis. A Photographic History of the University of Arizona, 1885-1985. Tucson: University of Arizona Foundation, 1987.

“Campus Arboretum.” University of Arizona. Accessed June 25, 2016. https://arboretum.arizona.edu/.

Nequette, Anne M., and R. Brooks Jeffery. A Guide to Tucson Architecture. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2002.