140 New Montgomery

When it was completed in 1925, the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph (PT&T) Headquarters was the tallest building in San Francisco. It was one of a pair of massive telephone buildings built simultaneously at opposite ends of the U.S., in New York and San Francisco, that ushered in a new era for telephone building architecture.

Like its counterpart in New York, 140 New Montgomery housed a complex array of white-collar and industrial functions. It served as the headquarters for the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company, providing executive, management, billing, and advertising offices on its upper floors, and it also contained telephone exchange equipment and a traffic engineering office. The integration of infrastructure and management was deliberate in prewar telephone buildings and reflected the enormous pride the Bell-affiliated companies took in the actual physical, technical nature of telecommunications engineering. When the building was completed, PT&T held a public open house on December 31, 1925 and more than 2,500 people toured the entire structure.

Architects Miller and Pflueger won the commission by charming PT&T president George McFarland and through Miller’s good relationship with PT&T building engineer Edward Cobby and his friend Alexander Cantin, who became the project’s associate architect. Together they planned a 26-story building with a truncated E-shaped plan that brought light into the interior volume, which occupied the full block along New Montgomery Street between Natoma and Minna streets. An elevator bank occupied the central bar of the E, with two office blocks extending on either side. Its location south of Market Street, in the area known today as SOMA, provided a location that was close to primary business clients and the city government at Union Square on the north side of Market. At the same time, by locating south of Market, the company chose a site in what was then a light industrial district with lower property values that made its construction economically feasible.

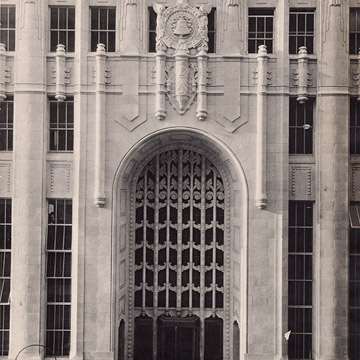

This was the city’s first setback skyscraper, with two slight setbacks at the 18th and 24th floors. The building is clad almost entirely in terra-cotta, with deep sculptural panels emphasizing a series of vertical flutes defined by continuous pilasters that draw the eye upward along the facade. An enormous terra-cotta Bell logo sits directly above the main entrance—something that not all the regional headquarters buildings featured. In California, the Bell monopoly had competition from local companies through the early 1920s, and there was emphasis on brand identity to distinguish the might of PT&T from the Home Telephone Company’s strictly local reach. Contemporary commentary emphasized the building’s modernity and its departure from historical form language, though there are clear echoes of Renaissance details in the colonnettes and arched windows, as well as ogee arches inspired by the swirling clouds of Chinese art above the doorways and passages.

Gladding, McBean supplied the terra-cotta for the building and it was, at the time, the largest single order the company had filled. All the pieces were designed and manufactured at their factory in Lincoln, California. Ornamental flourishes included massive eagles at the building’s top parapet, perched along the skyline as symbols of American ascendancy. Columns formed by miniature bells ornament the spandrels beneath the windows. The shine of the glazed white terra-cotta in the sunlight and the dramatic lighting of the setback parapets at night completely redefined the San Francisco skyline. PT&T argued that in its materials and form the new tower expressed San Francisco itself: “...it fits into the city’s thoroughly western makeup and surroundings.”

In the building’s lobby, Timothy Pflueger’s virtuosic handling of ornament dramatically shifted the building’s aesthetic. If Pflueger intended it to be “western” on the exterior, it was “eastern” on the interior. Elaborate murals inspired by an orientalizing view of Chinese art and design created an opulent public space for customers and employees. Horned deer and phoenixes floated in a field of stylized clouds created in incised, painted plaster. Black marble, brass, and gilded fixtures provided the backdrop for the oranges, greens, and blues of the murals. The auditorium on the top floor was adorned with romanticized scenes of flora and fauna of the East in plaster relief panels, including elephants, wolves, and cobras. Pacific Telephone considered this “oriental” style appropriate to a city that bridged the American and Asian continents. The undersea cables that connected North America to Asia by telephone left from Oakland, and San Francisco’s Chinatown was home to a much-publicized telephone exchange run by Chinese-speaking operators—the only telephone exchange in the entire Bell system to have non-English–speaking operators.

PT&T also used the building as the backdrop for numerous publicity stunts, including hosting famous visitors (like Winston Churchill, who visited the roof in 1929 for a view of the city, and the boxer Billy Alger, who posed for photographs with the building as a backdrop in 1926) and staging one-offs like the world’s longest football pass (the ball was thrown from the building’s roof to a receiver on the sidewalk below) or a speed-climb to the building’s roof by a retired mountain guide (Joseph Olberman completed the climb in less than nine minutes in 1927).

After the breakup of the Bell monopoly, Pacific Telesis took over the building and AT&T sold it in 2007 as part of a larger, long-term campaign to reduce the company’s massive real estate portfolio. Developer Wilson Meany worked with Perkins and Will to restore and repurpose the building for high-tech offices, removing and recycling the old copper wiring and replacing it with fiber optic cables. In 2013, Yelp began leasing space in the building to serve as its headquarters. Today 140 New Montgomery is an anchor of the SOMA district, directly adjacent to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and surrounded by arts institutions and tech offices.

References

“140’s Pushing Forty.” Pacific Telephone Magazine, November 1963.

“Editorial Comment.” Shapes of Clay 1, no. 6 (December 1925): 7.

Cahill, B. J. S. “Telephone Building, San Francisco, Calif.” American Architect 129, no. 2493 (March 20, 1926): 367-372.

Madrigal, Alexis. “A 26-Story History of San Francisco.” The Atlantic. March 19, 2014.

Poletti, Therese. Art Deco San Francisco: The Architecture of Timothy Pflueger. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.