You are here

Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption

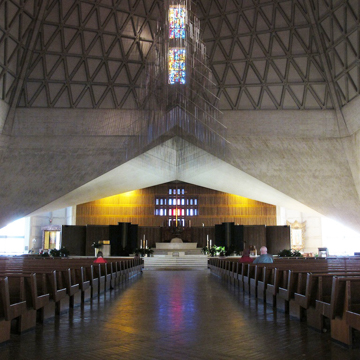

Atop San Francisco’s Cathedral Hill sits the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption, a study in structural expressionism. Eight hyperbolic paraboloids of reinforced concrete clad in travertine hang from a 190-foot-high steel structure. At its top, the steel structure takes the form of the Greek cross; the thin paraboloids, averaging 5.5 inches in thickness, sweep down to resolve in a square plan. The building—“Our Lady of Maytag,” as its neighbors have christened it, for its vague resemblance to a washing machine agitator—sits on a roughly cruciform plinth of brick, limestone, and concrete that hovers over sunken courts for cars.

Until 1962, another structure stood on this site. Built in 1887, the Victorian Gothic, red brick cathedral had recently celebrated its 75th anniversary when it was gutted by fire in September of that year. Archbishop Joseph T. McGucken began a fundraising campaign and quickly raised $15.5 million, $6 million of which was earmarked for a new cathedral. Taking cues from San Francisco’s Mission Dolores (dedicated 1791), Monsignor Thomas J. Bowe sought a California Mission style for the building and, bypassing the diocese’s building committee, McGucken announced the appointment of the little-known local architecture firm McSweeney, Ryan and Lee in April 1963. The archbishop worried about the cost overruns that had plagued Baltimore’s Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in 1959 ($12 million) and Hartford’s Cathedral of St. Joseph in 1962 ($14 million). Backlash was swift, however, and donors saw the choice of architect as a missed opportunity for the design of a new icon to engage the city’s public. Allen Temko, the architectural critic to the San Francisco Chronicle at the time, condemned McSweeney, Ryan and Lee’s work; their buildings, he criticized, “now disfigure large areas of San Francisco.”

The firm continued on amid the public controversy. But early iterations in the Mission Style and in the Romanesque did little to quell public worry, and McGucken called on prominent theologian Godfrey Diekmann to consult on the issue. Diekmann, like the public, disliked the proposals and solicited the archbishop to forgo any traditionalism in the project’s design. Diekmann suggested hiring Pietro Belluschi, then the dean of Architecture and Planning at MIT, as a consultant, which McGucken did in 1963.

Trained as an engineer but an architect by practice, Belluschi had already designed twenty churches by this point but worried about taking on a project of this scale. Through a series of iterations, Belluschi developed a concept of structural expression meant to evoke the modern age: if the medieval cathedral was a manifestation of its particular time, so, too, should the modern cathedral relate to its present, he reasoned. By September 1963, Belluschi fixed upon a warped surface envelope as his design concept. Here, Belluschi explicitly cited the influence of Eduardo Catalano, a colleague at MIT, who deployed a single hyperbolic paraboloid to serve as the roof to his house in Raleigh, North Carolina, completed in 1954. Belluschi, however, omits any reference to Kenzo Tange, who designed another St. Mary’s Cathedral in Tokyo slightly earlier. Like Belluschi's design, Tange’s is topped by a cross—albeit not the radially symmetric Greek cross Belluschi elected to use—with eight hyperbolic paraboloids sweeping down to the ground. Tange’s building was already well under construction in 1963 and was completed at the beginning of 1964.

Owing to his design’s ambitious, non-Euclidean geometry, Belluschi turned to the expertise of engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. Though engineering firm Leonard Robinson and Associates was already on board the project, Archbishop McGucken agreed to hire Nervi as a structural consultant. Together, Belluschi and Nervi produced a series of design iterations. Nervi produced test models of these, the early designs of which Belluschi deemed “discouraging.” At the Istituto Sperimentale Modelli e Strutture in Bergamo, Italy, Nervi tested these models for performance and appearance: some models attempted to resolve how the paraboloids would meet the ground, while others tested the effects of gravity loads and seismic activity. Nervi built a 1:100-scale model for wind tunnel testing, 1:40- and 1:37-scale resin models for seismic testing, and a large 1:15-scale model in reinforced concrete for gravity load testing. For Nervi, this sort of experimental testing allowed the engineer to resist fixed standards and to develop a level of design freedom; it was the model lab that became for him a site of experimentation and verification that allowed the engineer to develop new limits and new forms. Through these tests Nervi determined that in order to both accommodate the seating requirements and rigidify the building, the paraboloid structure would have to be scaled down and placed atop a larger, square base. Nervi sent the resulting drawings to the American engineering firm, where the design was tested in digital space on the MIT-developed STRESS computer program.

It is not completely clear where authorship of the building can be attributed: Belluschi, it seems, developed the primary form of the building, though some reports attribute a greater share of this task to Nervi. Although McSweeney, Ryan and Lee remained listed as architects to the project, while Belluschi and Nervi are documented as consultants, the latter two reportedly had complete control over the building’s design. Together, the conglomeration of designers and engineers developed a set of key engineering innovations that allowed for the erection of the building. The thin, hyperbolic paraboloids were made of four layers: two layers of precast concrete pans, a layer of pneumatically sprayed gunite, and a layer of travertine facing tiles. The exterior tiles required the development of a shear connector, while triangular ribbing on the interior, recalling the Gothic style, strengthens the thin surface. The weight of this structure comes down on massive hollow vaulted arches containing steel trusses; these arches spring from four equally massive piers, tied by prestressed cable to the ground, that narrow and then buttress outward. At ground level, these piers measure 15 by 24 feet, but they continue to widen as they extend further into the ground.

On each of the building’s four sides, György Kepes’s stained glass bridges the 6-foot gaps between the shells. Overhead, these gaps turn and culminate in the Greek cross form, which is also filled with stained glass of Kepes’s design. Belluschi brought Kepes, who was then a professor of visual design at MIT, onto the project. The designer, who was interested in the psychological effects of light, had curated the Light as a Creative Medium exhibition at Harvard in 1965. Though Archbishop McGucken asked Kepes to include symbolism in his design, Kepes insisted that the stained glass remain non-figurative and that its effect—casting fields of light—would take precedence over its content. Kepes allowed, however, an element of symbolism: the west window is red to represent fire, the south gold to represent air, the north blue to represent water, and the east green to represent earth. Atop, the Greek cross is rendered in amber. Hanging from the amber cross is Richard Lippold's 120-foot-tall baldacchino, which suspends 14 tiers of triangular aluminum rods with thin gold wire; a gold crucifix hangs at its center.

Forced to make a number of changes to his initial vision, McGucken worried that the work increasingly verged on neo-Puritanism or even iconoclasm: McGucken had first envisioned a revivalist architecture ornate with symbolism and figuration. Instead, faced with opposition on a number of fronts, abstraction and reduction ruled the day. And as if to confirm his suspicions, of the key members of the design team, only Nervi was a practicing Catholic. But it was not merely the architectural team that produced a design counter to McGucken’s aims—the cause was equally liturgical. In 1962, a month after the first cathedral’s destruction, the Second Vatican Council formally opened, with an aim to bring the church in line with the contemporary world. A new liturgy emerged from the three-year council: the church should focus, the council directed, on oneness, unity, and integrality. The effects of this statement were architectural as much as they were liturgical. The council recommended that new churches should focus on single, unobstructed spaces, where the sanctuary, nave, baptistery, and narthex could be united. The effect of these design standards, it was hoped, would unite congregation and priest. Though predating the council directive, Belluschi’s design conformed to the liturgical changes, validating his vision over McGucken’s. St. Mary’s freestanding altar sits slightly elevated, surrounded on three sides by congregational seating. The seats fan outward such that no seat is more than 100 feet from the altar, and all are united under the canopy of Belluschi and Nervi’s ribbed hyperbolic paraboloids.

But controversy continued. The new liturgy also sought to address calls for the church to take on problems of poverty and social justice. Meanwhile, construction of St. Mary’s was a massive endeavor: 1.8 million board feet of wood were used for the mountainous scaffolding required to construct the concrete shells and, after three years of construction, costs rose to $9 million. Community members, calling on the church to address problems of affordable housing and poverty, saw the project as wasteful. The first Mass held at St. Mary’s in October 1970 took place quietly with little publicity and no formal invitations. Six months later, owing to a fear of bomb threats, the building was sealed off in preparation for its dedication. Protests quickly followed that event.

The building maintains its status as symbol. For Nervi, the building united the scientific and the aesthetic, central to his project as outlined in his 1945 Scienza o Arte del Costruire. This, for Nervi, tied the building to its present: “it could only have been conceived today,” he proclaimed. For Belluschi, the building manifested structural expressionism, achieving a “kind of simplicity that becomes both structure and symbol.” But the cathedral was perhaps more so a symbol of a new Catholic church. And in this symbolic power, St. Mary’s galvanized a community and produced new forms of critical and political engagement.

References

Gaffey, James P. “The Anatomy of Transition: Cathedral-Building and Social Justice in San Francisco, 1964-1971.” Catholic Historical Review 70, 1 (January 1984): 45-73.

Goldberger, Paul. “Pietro Belluschi, 94, an Architect Of Major Urban Buildings, Dies.” New York Times, February 16, 1994.

Melaragno, Michele. An Introduction to Shell Structures: The Art and Science of Vaulting. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991.

Sennott, R. Stephen, ed. Encyclopedia of 20th Century Architecture. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004.

Sousa Cruz, Paulo J. da. Structures and Architecture: New Concepts, Applications and Challenges. London: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

“St. Mary's, Gothic Grandeur, Space-Age Verve.” Engineering News-Record 182, no. 2 (January 1969): 32-34.

“St. Mary's Gutted by Fire - This Forgotten Day in S.F.” SF Gate, September 8, 2015.

Torgerson, Mark A. An Architecture of Immanence. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007.

Whiffen, Marcus, and Frederick Koeper, American Architecture: 1860-1976. 2nd vol. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1984.

Wilkes, Joseph A., and Robert T. Packard, eds. Encyclopedia of Architecture: Design, Engineering & Construction. 1st vol. New York: Wiley, 1988.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.