The Glen Park Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station is a leading example of modern architecture in the Bay Area, significant for inflecting Brutalism with regionalism. It represents the intervention of the Bay Area Transit system into San Francisco’s neighborhoods, shows the collision of modern infrastructure with a residentially scaled commercial area, and, in revealing the architect’s working methods, demonstrates the international and cosmopolitan ambitions of the BART system.

A summa of Ernest Born’s career, the Glen Park BART station combined the designer’s long engagement with international modernism and graphic design with a subtle expression of regionalism and placemaking. The building is little more than an open-air mezzanine with a glass butterfly roof that floats above a platform boldly cut by a stair and escalators. It is in the disposition of the parts, the careful detailing, and siting that Born created a significant piece of architecture that belongs among the icons of Bay Area modernism.

A number of BART stations turned to the gritty language of Brutalism. Born molded the rough concrete into jagged, colliding forms that are simultaneously monumental and delicate. The approach from the southwest is particularly telling: here, the glass roof alights on tilted concrete walls that, with near Constructivist brio, act as purlins that sink into the massive reinforced concrete beams whose ends cantilever out dramatically, like the end beams of many Bay Area residences. Only here, the effect is far from woodsy or domestic. It is, instead, a kind of mannerism. The double game of magnifying proportions and transcribing a wooden architecture into concrete, with its ostentatious demonstration of tension and joinery, continues with the Brobdingnagian ridge-beam that thrusts itself into public space. The composition—for that is what it is—begs for analogies to machines or animals, probably prehistoric. This “neck,” replete with a drainpipe eye, articulates the “utility beam” that runs through the station. Above this, the structural members of the roof extend several feet beyond the glass layer. These are gouged into maws like Bernard Maybeck’s redwood dragonheads at the Faculty Club at the University of California, Berkeley, where Born was educated.

This is an appropriate language for the violent intervention of infrastructure into the village-like Glen Park, which sits about five miles southwest of downtown San Francisco. Born had to work with an irregular site framed on one side by small houses with first floor storefronts, many of which are survivors of earlier eras. On the other side, the station abuts a belt of more than twenty lanes of street, highway, and ramp, with a web of overpasses that forms a dense thicket of transit. While from some angles the station reads like the highway, it also buffers this belt of infrastructure visually and sonically. To soften the effect further, Born provided a civic remedy: a human-scaled plaza that faces the village.

The architect came to the project with unusual preparation. As the designer in charge of BART’s signage and typography, he had scoured European and North American stations and public spaces, photographed them extensively, and collected examples of maps, brochures, and other ephemera. In London, Stockholm, Cologne, and Aachen, he trained his eye on signage, paving schemes, plantings, street furniture, and wall treatments. Hundreds of photographs attest to his interest in both high and everyday design as he found them in subways, airports, and public spaces. He continued his research in Boston and Chicago, as well as closer to home at Oakland’s airport.

At the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal, Born studied the new subway system, bridges, and roads coursing through the megastructures that Reyner Banham would soon celebrate. This was a novel form of urbanism in which the building performed nearly as a plug-in to a wider circuit of movement systems, a plug-in with monumental and picturesque potential, two elements conspicuously missing from earlier incarnations of modern architecture. Montreal’s stations were part of this urbanism. They vary considerably, but in many of them Born would have seen elements he could use at Glen Park: raw, but exquisitely finished concrete; concourses that rise up like space frames for escalators and to catch light; and concrete arches and beams thickened to conceal the electrical and HVAC systems. Montreal’s stations are tough and urban, but also sensuous and urbane, with occasional outbursts of art. At the University of Montreal Metrostation, a wall of brick and hollow tile easily could have supplied the model for Born’s marble wall at Glen Park Station.

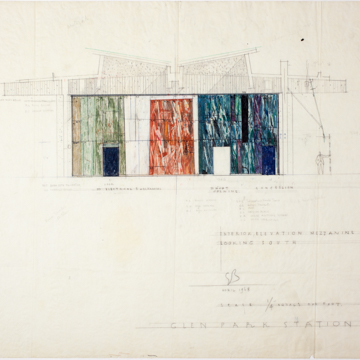

For this wall, which greets travelers as they enter and exit the station, Born traveled to Carrera, Italy, to personally select the marbles. Because there was no budget for art, he arranged the marble pieces so that the “mural” could be constructed with ordinary labor costs. His drawings for it suggest a labor of love. Born was also a master muralist and graphic designer who understood how the treatment of surface can shape a room or the larger experience of a spatial sequence. This marble abstraction sits below the “utility beam” and, humorously, suggests a red door in a white void at the primary visual pivot of the building. Elsewhere panels of Montana slate on the platform walls and white marble floors contrast with the imposing concrete massing and sleek escalator.

The overall result is a play of surfaces and structure that is unapologetically sensual and referential. In fact, the overhangs and pergolas of the Bay Area, while not at first apparent, become a signature note of the building. Pergolas shelter the exterior ticket booth and nearly fold into the vertical over the entrance as a form of visual and climatic protection. In these gestures, the station somehow resolves the urbane modernism of Northern Europe with Bay Area regionalism.

References

Banham, Reyner. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past. London: Thames and Hudson, 1976.

Ernest and Esther Born Collection in the Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley.

Olsberg, R. Nicholas. Architects and Artists The Work of Ernest and Esther Born. San Francisco: The Book Club of California, 2015.

“Two BART Stations.” Architectural Record(November 1974): 113-116.