You are here

Hanna House

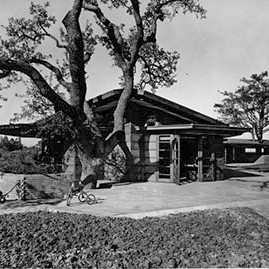

The Hanna House was an experimental project for both architect and client. Frank Lloyd Wright designed the house in 1936, and it was built on the southern edge of the Stanford University campus near Palo Alto, as a prototype of his new ideas for the “Usonian house.” Conceived of as a modest house for the American family, Usonians were meant to be modern in their construction and function, yet traditional in values. The Usonian house was the backbone of Wright’s plan for Broadacre City, his vision of a decentralized America. As a response to what he perceived as the anonymity of International Style architecture, Wright designed each Usonian house to be a building of “integrity”: a house that was integral to the site, to the environment, and to the lives of its inhabitants.

Paul and Jean Hanna were ideal clients for Wright’s new ideas. Like Wright, they believed that a house had a significant impact on the social development of its inhabitants. As educators, the Hannas were concerned with the environmental component of the learning process and a building’s ability to adapt to changing conditions. They found that Wright’s ideas about organic architecture and the role of the machine resonated with their own values. For the Hannas, Wright was a perfect fit both architecturally and pedagogically.

Though they asked Wright to design their residence in 1931, it was not until Paul joined the faculty at Stanford and relocated his family to Northern California in 1935 that work began in earnest. The Hannas and Wright spent much time together discussing the house, despite the fact that they had not settled on a site. In 1936, Wright sent plans for a spacious but not “unduly extravagant” house organized around a nontraditional hexagonal module. In the note that accompanied the plans, he wrote, “I imagine [the drawings] will be something of a shock, but perhaps not....” The Hannas were indeed shocked by the nontraditional exercise in geometric patterning, but they were swayed by Wright’s conviction that the hexagon module was the way of the future. Other than at Ocotilla, Wright’s temporary desert camp of the late 1920s, the Hanna House was the first time the architect deployed a non-rectangular geometry as a compositional technique. Wright described the hexagon as an experiment, attempting to demonstrate that the “cross-section of a honeycomb has more fertility and flexibility where human movement is concerned, than the square,” and he argued that the obtuse angle is “more suited to ‘to-and-fro’ than the right angle.” In the Hanna House, the flow and movement enabled by the hexagon became “a characteristic lending itself admirably to life, as life is to be lived in it.”

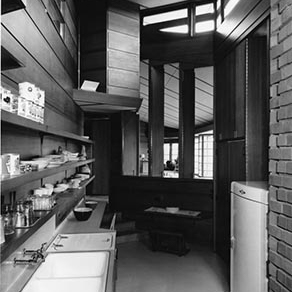

The hexagonal module was the organizing principle of the entire 3,750-square-foot house. Applying this module to the hilltop acre and half of the land the Hannas had on long-term lease from Stanford, Wright ordered the house around a 120-degree angle on Frenchmans Road and oriented toward the southern views of the California Crest mountains. The northern half of the house anchored it to the top of the sloping site and was composed of the study, master bedroom, and three children’s rooms. The house’s southern half, containing the living room and playroom (the two main rooms) projected outward: visually through perfectly framed views and physically through the extension of the terrace. The kitchen, which Wright called “the laboratory,” was located in the center of the house, lit from 15 feet above, and connected the more formal spaces. The masonry fireplace, as in many of Wright’s buildings, acted as a hinge point in the plan, and projected well above the pitch of the roof.

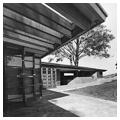

Local contractor Harold Turner built the house and later became one of Wright’s most trusted experts in constructing Usonian houses. The Hanna House had a small cellar for the heating system but, like most Usonians, was erected slab-on-grade, with two slabs of three-inch-thick concrete reinforced by wire mesh and bars. Building the house along the non-rectangular geometry was a complicated process. The top floor slab was colored with red oxide and the hexagonal unit was scored into its surface; where walls would later be added, metal strips were inserted into the freshly poured concrete with exacting precision. Stud and sash walls were mounted to the metal strips. All walls were built along the hexagonal grid lines, meeting at the 120-degree angle. Throughout, Wright favored what he called “natural” materials: the walls were clad in solid redwood board and batten, the roof was a thin copper sheet, and all masonry was common red brick.

The character of the Hanna House derives from the sense of expanding geometry: walls and furniture provide both a sense of physical enclosure as well as a visual connection to adjacent spaces. Surrounded by terraces, most rooms had direct access to the outside through folding glass doors. Each space had contrasting high and low ceilings, which allowed for different senses of scale within the same room. The living room, as Paul Hanna described it, “could accommodate a group of seventy-five and not seem crowded or noisy.” At the same time, it was intimate enough for two people sitting alone. Wright’s characteristic eaves emphasized the varying roof lines: low overhangs to protect the interior from wind and rain, and high clerestories to let light into the kitchen and baths.

Wright designed the furniture to match the hexagonal layout of the house, including the beds, which were custom made by the Simmons Mattress Company. Most furniture was built in but with ample space in between to encourage movement. The children’s playroom was mostly empty to encourage imagination. Though the kitchen and original bedrooms were quite small, everything always appeared to be connected to something just beyond it; the design was directed toward the ease of movement. “There are no protuberant corners,” Wright wrote, “it all flows.”

The house was originally budgeted at $15,000, but construction costs eventually topped $37,000. Nonetheless, the Hannas remained committed to the project and were particularly concerned with the house’s ability to adapt to their family’s changing needs, which Wright accommodated as an integral part of the construction system. The interior walls, for example, were non-load bearing to allow for easy reconfiguration. Twelve years after they moved in, the Hannas added a guest house, workshop, and storage room adjacent to the carport. In 1957, after their children left home, the Hannas again turned to Wright to reconfigure the smaller bedrooms into one large master suite. Additionally, the study was converted to a library and the playroom was turned into a formal dining room. In 1961, the Hannas hired William Wesley Peters, the senior architect at Taliesin Associated Architects and Frank Lloyd Wright’s son-in-law, to design and build a garden shelter and water features according to the original 1936 plan.

In 1974, the Hannas donated their house to Stanford University, as a “living example” of Wright’s philosophy and design principles. It was subsequently used as the university provost’s house and as accommodations for visiting faculty. It has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was also designated a National Historic Landmark.

The house, built along a branch of the San Andreas Fault, was significantly damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, due mainly to the structural failure of the central chimney and tower. The tower held much of the weight of the roof, which had been changed from the copper sheathing to a heavier combination of rust red tar and gravel in 1952. The 120-degree angle of the walls provided little shear support to the house, which was thus unable to deflect the quake’s massive movement. The house was restored in the following decade and completed in 1999. It is currently open to visitors by appointment.

Paul Hanna’s archives are held at the Stanford University Library. They include extensive documentation of the process of building the Hanna-Honeycomb House.

References

Hanna, Paul and Jean. Frank Lloyd Wright's Hanna House: The Clients' ReportCarbondale: Southern Illinois University, 1987.

Dunham, Judith, and Scot Zimmerman. The Details of Frank Lloyd Wright: The California Work 1909-1974.San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994.

Hanna House Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California.

“Hanna House.” Stanford University. Accessed September 21, 2018. https://hannahousetours.stanford.edu/.

Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks, ed. Letters to Clients. Fresno: The Press at California State University, 1986.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. The Architectural Forum68 (January 1938).

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “Frank Lloyd Wright Designs a Honeycomb House.” Architectural Record(July 1938): 59-74.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “A Great Frank Lloyd Wright House.” House Beautiful105, no. 1 (January 1963): 54-113.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.