J. Pearce Mitchell Park is a 22‐acre community park built in 1957 to serve as a key public facility for a newly planned neighborhood in the City of Palo Alto. The park formed the center of a “super‐block” composed of schools, churches, a fire station, Little League fields, and senior living facilities. As one of the first of a new breed of community parks, Mitchell Park is an important example of innovative postwar park design that accommodated changing living patterns and placed greater emphasis on the exterior environment and more active forms of recreation. Mitchell Park’s designer was Robert Royston, an innovative landscape architect practicing in Northern California’s San Francisco Bay Area. At Mitchell Park, his unique and thoughtful solutions gave the park a special character that attracted a diverse public following.

Royston came to prominence in the years after World War II, while working with Garret Eckbo and later with Asa Hanamoto, following his initial training in the office of landscape architect Thomas Church. Although Royston initially pursued garden design, growing public demand for outdoor recreation spaces soon led him to design public parks. The postwar housing boom had produced many new neighborhoods and subdivisions for young and growing families, but these frequently lacked local parks. Royston understood the importance of these spaces, and the needs of these families, and he translated them into public facilities that provided a wide range of recreation opportunities for all age groups. Royston’s designs for public recreation began with the Standard Oil Rod and Gun Club, a private recreation facility for Standard Oil employees, and Krusi Park in Alameda, California. Comparing these projects with traditional public parks in the U.S., it is easy to understand what was innovative about Royston’s work. Most public parks were either naturalesque (heavily planted imitations of natural landscapes) or focused on metal play and exercise equipment. Although these types had satisfied the recreational needs of earlier generations, by 1950 their utility and public appeal was limited.

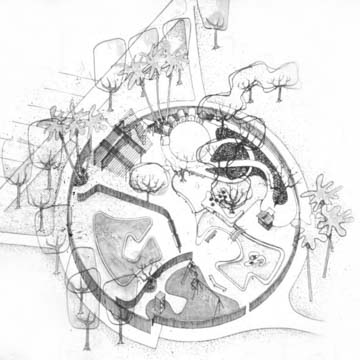

Royston’s design for Mitchell Park used patterns and ideas of modern art to create forms and geometry that were more functional and less formulaic (and symmetrical) than earlier park designs. Low curving forms and simple vertical lines within the park reflected influences from twentieth-century artists like as Alexander Calder, Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky, and Piet Mondrian. Royston incorporated ideas about landscape and gardens from non‐European sources, and paid special attention to the psychological, social, and actual physical needs of different user groups, particularly children. The tot‐lot encompassed a multi-story “apartment house” and slide, bear sculptures, a curvy wading pool, “gopher holes,” and even a “freeway” with a gas station and garages. Park light fixtures, inspired by the design of traditional paper lanterns, illuminated curving pathways. Royston designed these play areas by focusing on a child’s perspective, rather than an adult point of view. This meant manipulating the scale of the play area so that children, rather than adults, felt at ease.

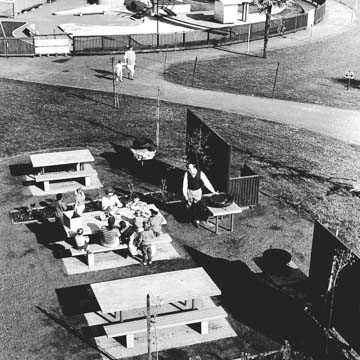

At the same time, Royston’s scheme for Mitchell Park still possessed elements of a residential garden, notably in the intimate scale of the individual design elements. Indeed, it is easy to imagine the barbecue/picnic area at Mitchell Park in a residential backyard in 1957. As Royston’s commissions grew in size, this residential scale disappeared.

Even a park beloved by its community cannot survive fifty years without renovation. In 2001, the City of Palo Alto rehabilitated Mitchell Park, maintaining its historic spirit but adapting the original design for more contemporary patterns of use. The city’s initial concerns for the rehabilitation were practical: to repair aging structures and bring them into compliance with current safety codes. The level of design modification required to comply with these standards alarmed members of the public, who, out of concern for preserving the park’s historic character, pressured the City to undertake a more sensitive rehabilitation. Fortunately, Robert Royston was interested in contributing to the project; the result was a rehabilitated park with a rolling, lush, mature landscape.

References

Rainey, Reuben M., and J.C. Miller. Modern Public Gardens – Robert Royston and the Suburban Park. San Francisco: William Stout Publishers, 2006