The heart of Stanford University’s campus, the Quadrangle or Quad, was different from the architecture of other American colleges and universities when it was constructed starting in 1887. Its grand scale, enclosed form, and monumental character can be understood only in the context of the founding motive of the school. In 1884 the only child of Leland and Jane Stanford died, and the bereaved parents resolved to use their great fortune—derived largely from Leland’s role in the creation of the western section of the transcontinental railroad—to build a university in their son’s memory. The resulting institution, officially named The Leland Stanford Junior University, was strongly shaped by this memorial motive.

For the physical planning of the school, to be located on their country estate south of San Francisco, the Stanfords hired Frederick Law Olmsted and the firm of H.H. Richardson in 1886. Since Richardson had just died, it was Charles A. Coolidge of the successor firm Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge who worked with Olmsted on the Stanford plan. Olmsted’s first proposed design, made during his visit to the site in September 1886, was similar to some of his previous campus plans, consisting of separate buildings arranged informally along curving roads in a park-like setting. But the Stanfords made it clear that they wanted something much more monumental and formally structured, with a large quadrangle, or group of quadrangles, and a memorial church as the focal point. (For one thing, Olmsted had probably not realized how much money the Stanfords intended to spend on their institution.) Leland had earlier been reported as saying that he intended “to be his own architect”; his control of the design process was to give the final plan much of its overall character.

During the winter of 1886–1887 in Boston, Olmsted and Coolidge worked on various arrangements of the quadrangular components of the plan, and in April 1887 Coolidge delivered their design to the Stanfords. But the clients were still not satisfied. Coolidge reported to Olmsted that after he staked out the quadrangle buildings on the site, the Stanfords insisted on several major changes, including moving the memorial church to a more prominent position. Coolidge added, “Both Mr. and Mrs. S. think the main entrance should be a large memorial arch with an enormously large approach and in fact the very quietness and reserve which we like so much in it is what they want to get rid of.”

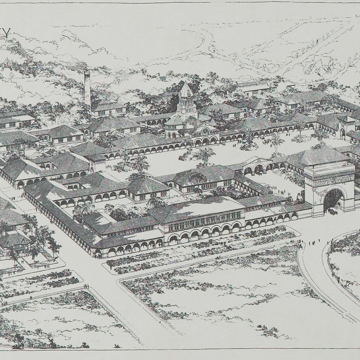

The design process was frustrating for Olmsted and Coolidge—especially for Olmsted, with his ideal of informal, park-like plans—but the final master plan for the university had a powerful clarity and integrity despite the difficult architect-client relationship. A mile-long approach from the Palo Alto railway station created a central, north-south axis, which passed under the Memorial Arch, through a Memorial Court and into the main space (the Inner Quadrangle), culminating at the Memorial Church. The Inner Quad was aligned along a secondary, east-west axis, which led into additional quadrangles for future expansion of the university. Surrounding the Inner Quad were groups of smaller courtyards and buildings that constitute the Outer Quadrangle. In contrast to most previous American colleges and universities, whose buildings were separate from one another, all the structures in this grand quadrangular scheme were connected by continuous arcades, creating an integrated ensemble. In its great scale and complex organization of spaces and linked groups of buildings, the design can be seen as anticipating the Beaux-Arts system of planning used in American campuses in the following decade.

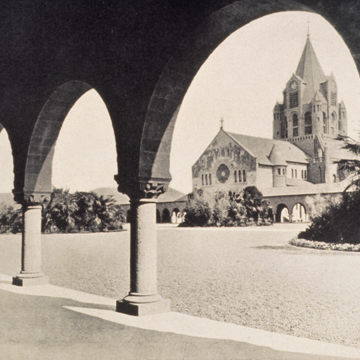

Since the Inner Quad was to be paved (except for eight circular planting beds), it had the character of an enclosed urban space. The Stanfords were, in fact, influenced by city squares they had seen during European tours, as well as the cloisters of the California mission churches. But the architecture itself, designed by Coolidge, was fully in the Richardsonian Romanesque style of his mentor, evident especially in the tower of Memorial Church, patterned roughly on that of Trinity Church in Boston.

The cornerstone of the Quad buildings was laid in May 1887, although the plans were not fully complete. Construction proceeded and the Inner Quad buildings were in place, except for Memorial Church, when the institution opened in 1891. After Leland’s death in 1893, control of the university was in the hands of his widow, Jane, who continued construction of the Quad buildings, despite having to deal with serious financial difficulties that followed her husband’s death. Olmsted and Coolidge were by now effectively out of the picture, and Jane relied on her own advisors and local architects, making changes in the design, especially in the facade of Memorial Church, where large areas of mosaic were introduced. The Outer Quad buildings and the immense Memorial Arch, however, were constructed largely as in the master plan. At the time of Jane’s death in 1905, the complex was mostly complete.

The devastating earthquake of April 18, 1906 caused great damage at the University, including the destruction of Memorial Church and Memorial Arch. In the repair and reconstruction of the Quad buildings that occurred in the following years, the church was reconstructed, but without its tower, and the arch was not rebuilt.

In succeeding decades, the University constructed new facilities, largely abandoning the original master plan that called for additional quadrangles aligned along the east-west axis. Most new buildings, however, retained architectural features of the Quad, such as red-tile roofs and sandstone walls. Starting in the 1970s, a series of restoration projects were undertaken for the Quad buildings, and the surface of the Inner Quad was given masonry paving for the first time (replacing previous gravel and asphalt surfaces). In the 1980s a master plan was created for a new Science and Engineering Quad, to the west of the main Quad, and the existing buildings in that area were gradually replaced with new structures, forming a quadrangular space aligned with the east-west axis of the original master plan. In this and other ways, a new appreciation of the Quad has developed in recent years, and it remains a guiding force in the physical planning of the university.

References

Joncas, Richard, David J. Neuman, and Paul V. Turner. Stanford University: The Campus Guide. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

Turner, Paul V. Campus, An American Planning Tradition. New York and Cambridge: The Architectural History Foundation and MIT Press, 1984.

Turner, Paul V., Marcia E. Vetrocq, and Karen Weitze. The Founders & the Architects: The Design of Stanford University. Stanford, CA: Department of Art, Stanford University, 1976.