You are here

Bobby Dodd Stadium

In the South, as elsewhere in the country, the collegiate football stadium is a conspicuous landmark, typically sited on the edge of the campus, with space for parking. But in a constrained urban campus like Georgia Tech’s, the stadium has grown from a small playing field into a megastructure that looms over the adjacent buildings.

Initially a rugged field located behind the now razed Knowles Dormitory, the open ground known as the Flats was not conducive to a successful athletic program. Until Coach John Heisman arrived in 1903, Georgia Tech had lost considerably more games than it won. In 1905, when the school had only about 500 students, Heisman arranged for some 300 convict laborers from the City of Atlanta to level the field for play, clearing rocks and debris, removing tree stumps, and shoeing away the snakes, rabbits, and other creatures that inhabited the field. That fall, when Georgia Tech played its first football game on the new Flats, the team won 54 to 0. Student-built wooden stands were enlarged in 1913 with the construction of concrete grandstands, and further enlarged two years later. The construction of these grandstands was funded by John W. Grant, and the playing field was named for his deceased son, Hugh Inman Grant. These stands, located mostly on the field’s west side, provided seating for 5,600. This capacity was substantially enlarged in 1924–1925, when Robert and Company designed the east and south stands, bringing the seating capacity to 30,000 and initiating the distinctive concrete arcade still visible along Techwood Drive, despite significant enlargements to the stadium. In 1947, campus architectural firm Bush-Brown, Gailey and Heffernan, along with structural engineer Richard Aeck, dramatically cantilevered additional seating and a large press box over the west stands, bringing the seating capacity to 44,000. Another 4,105 seats were added by contractor J. A. Jones at the north end of the field in 1958–1959; additions to the upper decks of the east and west stands were made in the 1960s by Capital Construction and FABRAP Architects, respectively; and by the end of the decade, the seating capacity had reached 58,121.

Throughout this period, the playing field remained grass. In 1971, Astroturf was installed, followed by All-Pro surface in 1988; the field was returned to grass in 1995. Other changes marked the immediate periphery of the stadium: in 1986, the south stands were demolished to make way for the Wardlaw Building, although some south-end seating was reinstated in 2002, when the entire playing field was shifted about 30 feet to the north. In 1992, Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart, and Associates incorporated skyboxes into the Bill Moore Student Success Center, a building tucked under the upper west stands on the location of the former Knowles Dormitory. Other skyboxes and private viewing rooms were also incorporated into the surrounding buildings.

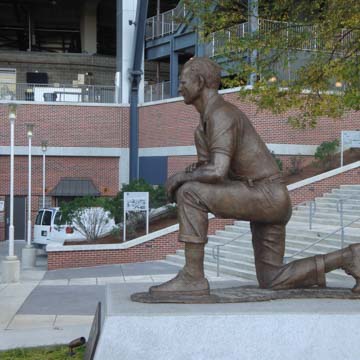

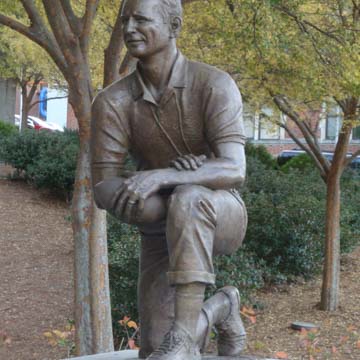

One of the most notable changes to the stadium occurred in 2003 with the construction of the $64 million north stands by HOK Sport, which provided 15,678 more seats on two levels. The development prompted the demolition of New Deal–era buildings along Third Street, including the Heisman Gymnasium and Swimming Pool (1934–1939), which was modeled on Paul Cret’s Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Under the new north stands is Calloway Plaza, which opens the stadium to Peter’s Park and contains various sculpture including an obelisk dedicated to school donor Fuller E. Callaway Jr., a bronze statue of John Heisman (1986, William M. McVey), and a bronze statue of Bobby Dodd (2012, Donald Haugen and Teena Stern Watson). Although Grant Field remained the name of the playing field itself, the surrounding stadium was named for Dodd in 1988. Fifty-eight years earlier, Dodd was first hired as a backfield coach, and in his subsequent career, led Georgia Tech to one of the most formidable records in college football history: 165 wins, 64 losses, and 8 ties.

The stadium has become a landmark megastructure that dominates the southeast corner of the campus. Today, football crowds approach 60,000 fans, and the stadium is an occasional venue for rock band concerts, visits by major public figures, and graduation ceremonies.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.