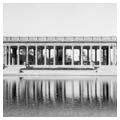

City Park’s origins date to 1850, when eighty-five acres of swampy land adjacent to Bayou St. John were donated by John McDonogh to settle his tax debts with the City of New Orleans. The City gained clear title to the property in 1858 and a contract was executed in 1872 with John Bogart and John Y. Cuyler, staff engineers in Frederick Law Olmsted’s office, for a park plan. Their scheme was rejected however, and there were few improvements until the 1890s, when the area was properly drained and additional land acquired. At that time, civil engineer George H. Grandjean, a member of the City Park Board, devised a master plan, and a local firm of surveyors, Daney and Wadill, was hired to work out the scheme of lagoons, footpaths, and bridges, with the help of architect Paul Andry (1868–1946). Based on City Beautiful concepts, the plan inspired several donors to fund structures, pavilions, and conveniences. The largest and most splendid building was the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art (OR75) of 1911, named for its benefactor and now known as the New Orleans Museum of Art. Other structures, all designed by New Orleans-based architects, included the Peristyle, a rectangular dance pavilion with rounded ends surrounded by an lonic colonnade, conceived in 1907 by Paul Andry and Albert Bendernagel (1904–1961); Emile Weil’s circular Popp Bandstand (1917), a replica of the Temple of Love at the Petit Trianon, Versailles, funded by lumberman John F. Popp; a refreshment pavilion known as the Casino, with triangular arches, created in 1913 by Nolan and Torre; a Beaux-Arts classical bridge (1923), given by Felix Dreyfous; a brick pigeon house (1928), perhaps by Dreyfous’s son, architect F. Julius Dreyfous; and a mechanical carousel (1910) in a pavilion built in 1906. The entrance to the park from City Park Avenue is marked by a pair of pylons with engaged Ionic columns, built in 1913. Alexander Doyle’s bronze equestrian statue of General P. G. T. Beauregard (unveiled in 1915) that stood in front of the entrance has been removed, one of four monuments in New Orleans related to the Confederate cause taken down from public sites in 2017.

In 1929, the Chicago firm of Bennett, Parsons and Frost was hired to draw up a new plan for the park, which by then had increased to thirteen hundred acres. Work could proceed only after the receipt of federal funding, first from the PWA and then the WPA. The park underwent a spectacular transformation that cost $13 million, of which the City Park Board paid only 5 percent. From 1934 to 1940, fourteen thousand men, using mostly hand tools, laid out golf courses on the east side of the park (supervised by landscape architect William Wiedorn), dug more than sixty acres of lagoons, and built eight new bridges, a stadium, fountains, and cast-concrete benches. Wiedorn (1896–1988) had worked in Boston (in the Olmsted Brothers office), Cleveland, and Florida before moving to New Orleans to supervise construction of the golf courses. He remained in the city and maintained a modest practice. Mexican-born sculptor Enrique Alferez, assisted by a team of sculptors, created both freestanding and architectural sculpture in a stylized Art Deco manner that suited the architectural forms. Particularly note-worthy is the Popp Fountain (corner of Marconi Boulevard and Zachary Taylor Drive), with waterspouts in the shape of leaping dolphins (recast in bronze in 1998), surrounded by a circle of twenty-six columns. The fountain’s site was developed by Olmsted Brothers; Wiedorn was the local project supervisor. The firm of Weiss, Dreyfous and Seiferth managed these federal projects.

Wiedorn and architect Richard Koch laid out the Botanical Garden and its structures in the 1930s. The garden was restored in the 1980s, and a multi-activity pavilion by Trapolin Architects was added in 1994. Particularly noteworthy in the garden are original benches, ornamental gates, and a sundial by Enrique Alferez, together with recent additions.

After 1965, the park acquired land on the lake side of Harrison Avenue in compensation for the intrusion of I-610. Now encompassing over sixteen hundred acres, City Park is one of America’s largest municipal parks and it contains one of the largest collections of mature live oak trees on public land. The carefully contrived irregular landscape, the plantings, the more than eighty species of trees, and the sensitively placed pavilions and sculptures give the park, despite its flat terrain, the romantic ambience favored by nineteenth-century urban planners. Flooding in 2005 in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina caused extensive damage, but new plantings and building repairs have restored this place to its former beauty. Among recent additions to City Park are Big Lake, a reconfiguration of the lagoon from the WPA era (2011, Cashio Cochran, landscape architects); the relocation of tennis courts to create a large passive green space; and a refurbishment of the Botanical Garden completed in 2007. Much of the funding for these post-Katrina improvements has come from national sources.