You are here

Richman Brothers Factory

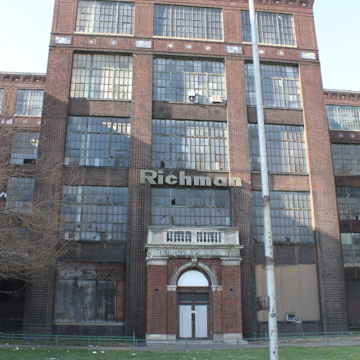

Richman Brothers was a leading American manufacturer of men’s clothing and this factory, completed in 1916 in a classical commercial style, played an important role in the development of the twentieth-century garment industry in Cleveland. Continuously for nearly eighty years, the building housed the company’s administrative offices, its production facility, and its warehouse, and also served as the distribution center for the retail and mail-order segments of the business. Richman’s successful direct sales operation stimulated enormous growth for the company, leading to five major additions to the original building between 1924 and 1929. Ultimately, this resulted in a five- and six-story, brick and reinforced concrete factory building that has over 17 acres of floor space. At the time the Richman Brothers Company factory was completed, it was said to be the first and the largest in the country to house its entire clothes-making and distribution operations under one roof.

Built on a commercial street in an otherwise residential neighborhood, the original Richman Brothers factory and all five additions were designed by Christian, Schwarzenburg and Gaede, a Cleveland architectural and engineering firm responsible for at least two dozen other factory and manufacturing buildings in the city between 1910 and 1929. Dana Clark, an architect who worked for the firm of Walker and Weeks from 1912 to 1947, collaborated with Christian, Schwarzenburg and Gaede on the design of the original building’s exterior, establishing the look and feel of the subsequent additions.

The factory was heralded for its design and physical presence, which grew as the Richman Brothers Company expanded. The original E-shaped building spans an entire block and is set back in the center behind a grassy lawn along the East 55th facade; the additions are located to the rear and together cover approximately two-thirds of the 6.5-acre site. The building has a main entrance with a stone balustrade and large entablature supported by projecting stone and brick pilasters. Secondary entrances are marked with a variety of decorative elements including projecting brick surrounds, stone pilasters and engaged columns, and inset double-leaf doorways. Slightly projecting brick piers mark the building’s bays and the exterior walls, clad in dark red brick, are enlivened with brick and terra-cotta of different shapes and sizes that create decorative panels on the vertical brick piers and the horizontal bands between the industrial steel sash windows. Square terra-cotta tiles in blue, green, yellow, and orange are inlaid singly and in patterns on the brick piers and along the parapet, adding a dash of color to the extended brick facades.

At the time of its dedication, a local newspaper described the building as “one of the most complete plants of its kind in the world” and noted that it was equipped “with every facility to make the working conditions of the employees ideal and to create among them a spirit of happiness in their work.” These likely included the high ceilings and the large and regularly spaced windows, which, together, provided ample light and air in the factory interiors. While some of the window openings have been filled in or boarded up, the original feel of the open plan and light-filled manufacturing floors remains surprisingly intact in most areas. The first floor of the original building contained a small main lobby with brick arranged to create decorative panels on the walls and terra-cotta tile floors. The remaining floors in the building are concrete; the columns and ceilings are concrete and the walls are brick.

The Richman Brothers Company garment manufacturing processes included departments for designing, shrinking, cutting, sewing, pressing, examining, and shipping. Motor-driven machines were used to fabricate all garments with each employee performing a single operation before passing the garment to another worker. A single pair of trousers passed through 49 pairs of hands, a vest 46, and a coat through 159 pairs of hands. When assembly was complete, an experienced tailor subjected each garment to final inspection. Only then was the garment was shipped to a retail stores or directed to a mail-order customer. Because of this process, Richman Brothers became known as the company of “Seven Hundred Fussy Tailors.”

Richman Brothers was the first to sell their clothing directly to customers from their own retail stores, a sales model that eliminated the wholesaler (middleman) and guided the company’s business plan for most of the twentieth century. The company’s mail-order business began direct selling through traveling salesmen. Here, too, the goal was to sell high-quality products from the factory to the customer, eliminating the wholesaler and keeping prices down. Salesmen sold door-to-door, and sometimes from touring Richman Brothers Company trucks. The trucks, painted with the company’s “No Middleman’s Profit” slogan, doubled as mobile advertisements and showrooms and they were fitted with lighted glass cases holding actual suits on forms; customers could view the latest Richman Brothers fashions and order a suit or topcoat that met their needs. By 1930, the Richman Brothers had 1,000 salesmen selling directly to customers across the country. Richman Brothers closed its mail-order division in 1942 due to the limited availability of fabric and patterns during World War II. In early 1943, the company reported to its shareholders that 50 percent of its production had been devoted to military garments. By 1948, there were 2,500 office and factory workers at the East 55th Street facility and another 1,300 employed in the retail stores.

Richman Brothers prided itself not only on production quality and value, but also on employee relations and benefits. The company relied on the large immigrant workforce available in the neighborhoods surrounding the factory, and its employees were apparently very loyal. When Cleveland garment workers went on strike in 1911 (they had begun organizing in 1900), Richman Brothers was unaffected by the strike and through the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s the company was never unionized as other factories were at the time. This was due in large part to the way the company treated its employees, providing higher wages, paid vacations, and stock in the company. Throughout its history, Richman Brothers Company maintained a policy of corporate paternalism, referring to its many employees as the Richman Family. When its East 55th Street factory opened, employees kept track of their own time and piecework and, unusually for the time, the company provided annual paid vacations: one week at Christmas and one week at July 4, during which time the factory shut down. In 1949, paid vacation was increased to three weeks. By 1950, Richman Brothers employee benefits included free life insurance, hospital and surgery benefits, double indemnity and dismemberment insurance, childbirth benefits, loans without interest, pay for holidays, medical expenses reimbursement, sick benefits, and pensions for any employee working 15 years. The company organized intramural sporting events held in the factory courtyards during and after work, sponsored company outings and events at places like Euclid Beach, and marked major holidays with employee lunches in the company cafeteria. Employees were also encouraged to become shareholders in the company; almost 100 percent of employees took advantage of this option. These policies continued throughout the company’s existence.

In 1969, the F.W. Woolworth Company bought out Richman Brothers, but the company continued to function as a wholly owned subsidiary. In 1975, Richman Brothers operated 279 stores in 39 states but in 1990, when Woolworth’s closed, it sold the Richman Brothers’ Cleveland manufacturing plant. Two years later the company had been liquidated and all of its stores were shuttered. The East 55th Street factory has been vacant since then. Chinese investors purchased the site in 2009 but no redevelopment plans have moved forward. The Richman Brothers Factory is individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its significant industrial architecture and its role in Cleveland’s garment industry history.

References

McCandless, T. L. “Richman Brothers-An Institution.” Based on an interview with Nathan G. Richman, Chairman of the Board, September, 1930. Richman Brothers Company Records, MS. 4664, Western Reserve Historical Society.

“Medal of Merit Awarded American Factory Building.” The American Architect14 (October 30, 1918): 525-532.

Rudge, Heather, “The Richmond Brothers Company,” Cuyahoga County, Ohio. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 2012. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.