The Ohio Statehouse is the most significant Greek Revival building in the state and its design places it high on any list of architecturally significant state capitols. A twenty-two-year construction period and a long list of architects suggest that completing a building to serve as the seat of Ohio government was no easy task. Columbus was chosen by the Ohio General Assembly in 1812 as the nine-year-old state’s permanent capital. In addition to a flood-free site on the eastern bluff of the Scioto River, the newly-platted community boasted a central location and—perhaps more importantly—an offer from the development syndicate pitching the site to build a statehouse and other state buildings on a ten-acre dedicated square, all at no charge. This proposal was accepted, and by 1816 the promised buildings had been erected and the developers had sold town lots for a tidy sum. The new Capitol Square was the central element of the Columbus town plan and remains so today.

The first Columbus statehouse was actually Ohio’s third. Earlier ones had been built in Chillicothe and Zanesville, the state’s previous capital cities; all three statehouses had the foursquare courthouse form that migrated westward during the early nineteenth century. Development of the state was so rapid that by the 1830s the original Columbus statehouse and an adjacent state office building were proving to be too small, and a competition was proposed to develop a design for a new capitol building. Henry Walter of Cincinnati won the competition and developed the original plans, but ultimately these were not followed. Hudson River artist Thomas Cole came in third and, even though his design was not selected, elements of his plan made it into the final scheme and were incorporated into the building. Indeed, Cole’s painting, The Architect’s Dream, has components that look very much like the Ohio Statehouse. Construction of the building, which was accomplished in part by penitentiary labor and with the local and highly fossiliferous Columbus limestone, began in 1839 and followed a rocky course strewn with political conflict. At one point in the 1840s construction stopped and the foundations were buried, necessitating their excavation some time later when work resumed. Loss of the original Columbus statehouse to fire in the early 1850s provided a major incentive to get the work done.

The new statehouse, which opened in 1861, had more than fifty rooms and incorporated some innovative features. It had four open light wells to provide daylight to interior rooms. It also had forced-air central heat; during the first winter occupants were overjoyed when interior temperatures reached sixty degrees. Flush toilets were in small rooms located in the massive stonework of the cupola base, and were reached by exiting onto balconies in the light wells; water was supplied by rain-fed storage tanks over the east and west porches.

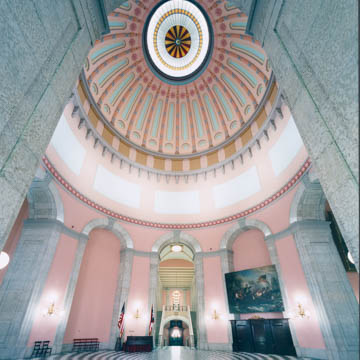

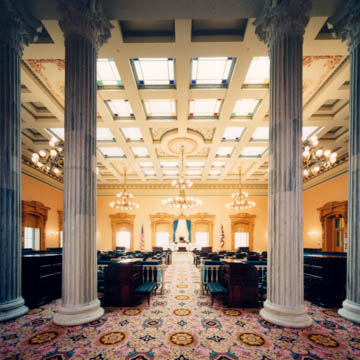

The severe Greek Revival exterior of the statehouse gave way on the interior to a more ornate character typical of the early Italianate era, further evidence of the many hands and the long construction period that brought the building into being. The principal interior feature was the soaring, domed, central rotunda, which rose to a colored-glass state seal. The rotunda floor features octagonal contrasting stone blocks—over 4,000 of them—laid in an intricate spiral geometric pattern; from it large, arched openings led to the main corridors. The house and senate chambers featured coffered ceilings with decorative plaster and colored glass skylights, white marble podium columns, and additional architectural detail.

Many people, seeing the Ohio Statehouse for the first time, wonder why the dome was never completed. To them the conical-roofed, drum-like cupola looks unfinished. While a dome was proposed when the building was under construction, this idea was ultimately rejected. Cost, more than anything else, was the deciding factor, but since the Greek architecture on which the exterior design was based did not employ domes, it was considered an appropriate decision. The cupola, however, is not merely decorative. A narrow spiral stair within the northeast cupola base leads to a viewing gallery through whose tall, narrow windows is a view of the city’s skyline. A wooden bench encircles the upper part of the rotunda dome so those fatigued by the climb can regain their breath.

The Statehouse originally housed the entire state government: the offices of the Governor, Auditor, and Treasurer; the House of Representatives; the Senate; Supreme Court; and State Library. The building was essentially complete by 1861 and opened that year, although finishing work continued for several more years. In 1901 the Beaux-Arts Judiciary Annex (later known simply as the Statehouse Annex and today the Senate Building) was completed as the home of the Supreme Court of Ohio. It contained two courtrooms, the law library, and associated offices and meeting rooms. The Annex had its own ornate rotunda with a colored-glass state seal. It was connected at its second level to the main level of the statehouse by an open-air plaza, a move that required demolition of the capitol building’s east side entry steps.

As the state government grew in size office space became a problem; over time the state moved offices to four different locations in Columbus. Various schemes to enlarge the Statehouse were floated over the years, but none went forward. The most expedient way to solve space problems was to work within the stone shell of the building. So the light wells were filled in with as many as five floors of offices; rooms were repeatedly subdivided; and basement spaces, where mechanical systems and horse stables were originally housed, were taken over for office use. By the 1980s the situation had become critical. The building’s fifty-plus rooms had been subdivided into more than 300; there were nearly a hundred different air-conditioning systems; and many dead-end corridors and confusing circulation patterns represented a real hazard. In addition, there was no appropriate and secure way for important government officials to arrive other than through a garage beneath the plaza.

In 1990 a project began to restore the statehouse and the annex to its original condition (or as close to it as possible). The main design challenges were to find documentation on both the original designs and changes over time, a task complicated by the scattering of files across several public and private repositories; to find and bring back to the buildings as many original furnishings as could be found; to determine original decoration and paint schemes; and to install entirely new mechanical systems in a way that was minimally visible, but that brought Statehouse to modern standards of safety and efficiency.

Careful restoration work was undertaken in the most important public areas: the two rotundas, the house and senate chambers, the main corridors, and the annex’s two courtrooms. Four other areas underwent innovative rehabilitation that turned them into visually striking and useful spaces. The statehouse basement, characterized by massive, load-bearing masonry walls and soaring brick, groin-vaulted rooms, became circulation, office, gift shop, and museum space from which a connection was made to the garage built beneath Capitol Square in the 1960s. The statehouse’s two western light wells were covered with glass roofs, and elevators and stairs were installed so the building would meet all safety codes and be fully accessible without major alterations to the masonry structure. Beneath the plaza, where trash was stored for removal and state-owned vehicles were washed, entirely new visitor reception spaces were created, including a classroom and adequately sized restrooms for the thousands of students who visit annually. At this level is the “Map Room,” a large stone map of Ohio’s eighty-eight counties depicted in various colors, which is a major attraction for children. Finally, the two buildings were linked by a third, the Capitol Atrium, a cantilevered structure that does not rely on either historic building for structural support. The atrium floor can accommodate several hundred people for public events, and its exterior was clad in Columbus limestone, specially quarried for the project, in a contemporary but compatible design respectful of the Greek Revival and Beaux-Arts designs of the statehouse and annex.

These three linked structures define today’s Ohio Statehouse, a working state capitol where the daily business of state government is carried on. Management of the complex has been placed in the hands of a single agency, the Capitol Square Review and Advisory Board, which has permanent review and approval power over all work undertaken in the buildings or on the grounds of Capitol Square. Significant sculptures and memorials are located on the square, including one dedicated to Christopher Columbus and another to President William McKinley. The These Are My Jewels statue commemorates important Ohio Civil War-era military and political figures. On the east side of the Senate Building the Ohio Veterans’ Memorial was constructed during the 1990–1996 renovation.

The Ohio Statehouse is a National Historic Landmark, designated as an outstanding example of Greek Revival public architecture.

References

Darbee, Jeffrey T. and Nancy A. Recchie. The AIA Guide to Columbus.Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2008.

Samuelson, Robert E., Pasquale C. Grado, Judith L. Kitchen, and Jeffrey T. Darbee. Architecture: Columbus. Columbus: Foundation of the Columbus Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, 1976.

Schooley Caldwell Associates. The Ohio Statehouse Master Plan.Columbus: Schooley Caldwell Associates, 1989.