Worthington was settled in 1803, the year Ohio became a state, and still it conveys its original New England heritage through an intact village green surrounded by early-nineteenth-century churches and houses. But just past the last clapboard house on South Street, the southern boundary for the original town plan, the street meanders into the neighborhood of Rush Creek, a collection of mid-twentieth-century modern houses inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian concept for affordable homes.

Rush Creek Village began with the construction of one house. In 1946, Martha and Richard Wakefield traveled to Taliesin West in Arizona to meet with Frank Lloyd Wright and returned to Ohio determined to have a house incorporating his organic architecture theories. The Wakefields were impressed with the work of Theodore van Fossen, especially the Gunning House, which he co-designed with Lawrence Cuneo and Tony Smith. Located east of Columbus, the 1940 Gunning House was an organically-designed house built on the edge of a ravine. Van Fossen, who had studied at what is now the Illinois Institute of Technology in the late 1930s, was a devotee of Wright’s architectural philosophies. Although he met Wright and worked on Wright-designed projects with Wright’s apprentices, Van Fossen never formally studied with him but his Wrightian credentials were sufficient for the Wakefields, who commissioned him to design their house in 1953.

Martha Wakefield had studied philosophy and art at the Ohio State University, and she contributed design ideas to the Rush Creek houses and furnishings. Richard Wakefield, a former designer at the Lustron Corporation, served as the builder and general contractor. In 1953, they bought a ten-acre parcel of land at the southern edge of Worthington. A wooded, rolling terrain with a creek and tributaries traversing it, the land was considered unbuildable by local contractors who were rapidly constructing post-World War II suburban housing. Together Van Fossen and the Wakefields created a modern home nestled in the surrounding landscape.

Throughout the country in the years after the war, returning veterans and the Baby Boom produced a tremendous demand for housing. Between the end of the 1940s and 1970, 1.8 million houses were built in Ohio; more than 180,000 in Franklin County, second only to Cleveland and the surrounding suburban growth in Cuyahoga County. The Wakefield House was built between 1954 and 1957; once construction started, the idea of developing an entire neighborhood quickly became a reality. In December 1954, the Rush Creek Village Company was formed, and through this entity, additional acreage was purchased. Van Fossen began to create a holistic design for the neighborhood, recording a plat in 1956. Rush Creek Village Company imposed deed restrictions, which minimized intrusions on the landscape and protected the architectural character of the neighborhood. Prospective owners were required to have their home designs approved in advance.

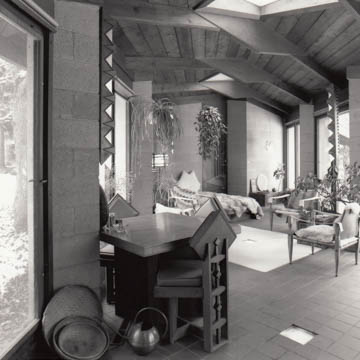

Van Fossen’s Rush Creek houses have many attributes of Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture in general and his Usonian houses in particular, including floor to ceiling windows allowing for maximum visual flow between interior and exterior spaces, natural materials, geometric forms, and integrated carports and furnishings. While borrowing from Wright’s architectural language, Van Fossen crafted his own design vocabulary for Rush Creek. He, too, adhered to an overall sense of horizontality, but also occasionally departed from it. For example, several houses have vertical bands of glass block that create a visual orientation away from the horizontal. Additionally, the 1966 Turner House (230 East South Street) has five stories, three above grade, and its cube-like massing links it to the International Style. Van Fossen experimented with angles and forms, combining different geometric shapes in one house, rather than using the same form as a repeated motif. To keep construction costs manageable, Van Fossen and Richard Wakefield used traditional balloon framing technique in the Rush Creek Village houses. Van Fossen more frequently utilized gable roofs with low pitches, instead of the flat roofs typical of Wright’s Usonians. He connected the individualistic houses to each other in subtle ways; for instance, Van Fossen aligned the fascia at the same height for the neighboring Orcutt and Cooper houses to create a visual link from the streetscape.

What sets Rush Creek Village apart is its overall harmony of design within the community and the integration of each house with its site and to the other houses. Each house is an individual design, but all share common building materials of wood, concrete, quarry tile, and glass to create a unified whole. With respect to the landscape, Van Fossen created a cohesive neighborhood. Lot lines were irregular and conformed to the topography instead of an imposed measurement system. Fences between properties were, and still are, banned to maintain the open continuity of the natural scenery. As houses were built in the community, they were situated for maximum privacy from neighboring houses and in harmony with the natural environment. From the street, many of the houses appear to be small one-story buildings, but in reality are multi-story buildings situated on a hillside.

Original owners in Rush Creek Village tended to be professionals such as psychiatrists and engineers, professors, or artists. Many families lived in their houses for decades and some are now in their second generation of occupancy. Van Fossen’s house designs were meant to grow along with the owners’ changing life circumstances; additions and guesthouses were common in Rush Creek Village. The Wakefields added on to their house in 1977. The Pepinsky family added a separate guesthouse to their property in 1958, a year after completion of their house. Corresponding to the main house and the adjacent round Orcutt House, the small, tadpole-shaped Pepinsky guesthouse is one of the most intriguing buildings in Rush Creek Village.

The majority of Rush Creek Village was completed by 1976, although houses, built according to deed restrictions, have been added as recently as 2011. By 1976, the Rush Creek neighborhood had fifty-three buildings, nearly all designed by Van Fossen. Until shortly before his death in 2010, Van Fossen continued to be consulted for design input in Rush Creek. While inspired by Wright, Van Fossen considered himself an independent artist: “…I do not ride on the coattails of Mr. Wright. His discoveries in a creative architecture for our time and for a new kind of space in architecture are not only impossible to ignore, they must be understood to proceed with one’s own work.”

References

Kane, Kathy Mast, Beth Brown, Dorothy Hogan, Tom Hogan, Dr. Pauline Pepinsky, and M. Scott Tedrick, “Rush Creek Village Historic District,” Franklin County, Ohio. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 2003. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Kelly, Darren M. Local Non-Locality: Sixty Years in Rush Creek Village. iBooks, 2014.

Weiker, Jim. “Architect designed Rush Creek Village,” The Columbus Dispatch, December 20, 2010.