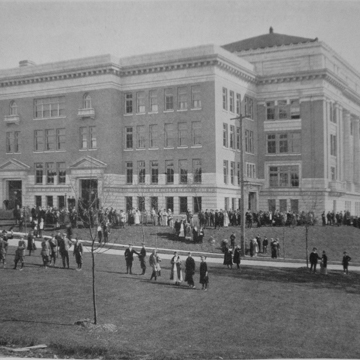

Stately, imposing, and grand, Seattle’s Franklin High School—dominating a hill overlooking the Rainier Valley in the Mount Baker neighborhood—is among the oldest and most beautiful schools in the Pacific Northwest. This was the second high school built in the city, established after Seattle High School could not accommodate an increasing student population at the turn of the century. To help ensure its grandeur, the city chose the site when the Mount Baker neighborhood was still under development in 1910 and purchased two lots west of the property to prevent any other buildings from obstructing the school’s view of the valley. The city also vacated a street in front of the school and landscaped it with grass and shrubs.

Edgar Blair was the district architect for Seattle Public Schools and worked on approximately 32 of the city’s schools between 1910 and 1919. Franklin High School was among those, and Blair gave it a Beaux-Arts flair in keeping with the design of several civic institutional structures during the City Beautiful Movement. The school was constructed using reinforced concrete and pressed brick with terra-cotta trim, and its west facade features five grand Palladian windows below an entablature and balustrade, separated rhythmically by massive engaged Doric columns. Although it is not the principal entrance, the grand, city-facing, classically detailed west facade permits comparisons with Renaissance palazzi.

The traditional facade notwithstanding, Franklin High School was to be as modern as possible—at least in terms of technology and function in accordance with contemporary needs or tastes. To this end, together with 42 classrooms and two gymnasiums, on the third floor was a lunchroom (so the smell of cooking would not disturb the students); a model apartment for the home economics classes; and a manual training room with machinery. To celebrate the progressive school, a model and pictures were displayed at Chicago’s 1933 Century of Progress Exposition.

By 1925, enrollment at Franklin High had swelled enough that expansion became necessary. The original 2.2 acres was increased to 10.6 acres and a 15-room wing on the east side, designed by Floyd A. Naramore, was added. Naramore had been appointed as district architect in 1919 and designed many of Seattle’s schools during the 1920s after compulsory attendance laws resulted in an influx of students. During World War II, the school was used by the U.S. Army for anti-aircraft training and commando training. A bronze plaque and memorial tree were dedicated following the end of the fighting, commemorating the 99 former Franklin students who had died during the war.

Enrollment had again increased beyond capacity by 1958, necessitating another expansion. John W. Maloney, a well-known Seattle architect who worked on many prominent university buildings around the state, provided designs for a girls’ gymnasium, music rooms, and a study hall—additions that obscured the west-facing facade. Additional detached buildings were also constructed for a boys’ gymnasium and woodshop. During the 1980s, another major renovation took place after an engineering study deemed the school vulnerable to earthquake damage. The Seattle-based firm of Bassetti Norton Metler Rekevics led that project, which included the construction of a small addition to the U-shaped plan of the school. A new wall built on the east side of the school encompassed classrooms and a new auditorium.

Still, in 1986, with maintenance costs on the rise and the school’s susceptibility to earthquake damage, the school board voted to tear down the building. Yet students, alumni, and neighborhood residents immediately rose in protest, and Seattle’s Landmark Preservation Board designated the school a city landmark. These actions underscored the historic and architectural value with which the community associated with the school, and it was saved from demolition. Another renovation included five separate artworks depicting the school’s history and the removal of the 1958 addition that had obscured the facade.

References

“Edgar Blair (Architect).” Pacific Coast Architectural Database (PCAD). Accessed September 7, 2015. http://pcad.lib.washington.edu.

Hancock, Marga Rose. “Bassetti, Fred (1917-2013).” Essay 8589. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, March 20, 2009. Accessed September. 7, 2015. www.historylink.org.

“John J. Maloney.” Architect Biographies. Washington State Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation. Accessed September 7, 2015. http://www.dahp.wa.gov.

MacIntosh, Heather M. “Naramore, Floyd A. (1879-1970).” Historylink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, November 2, 1998. Accessed September 7, 2015. www.historylink.org.

Pacific Builder and Engineer. Vol. 13. Seattle: Construction Publications/West (1912): 6, 159.

Thompson, Niles, and Carolyn J. Marr. “Franklin.” Building for Learning: Seattle Public School Histories, 1862-2000. Seattle: Seattle Public Schools, 2002.